—99→

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

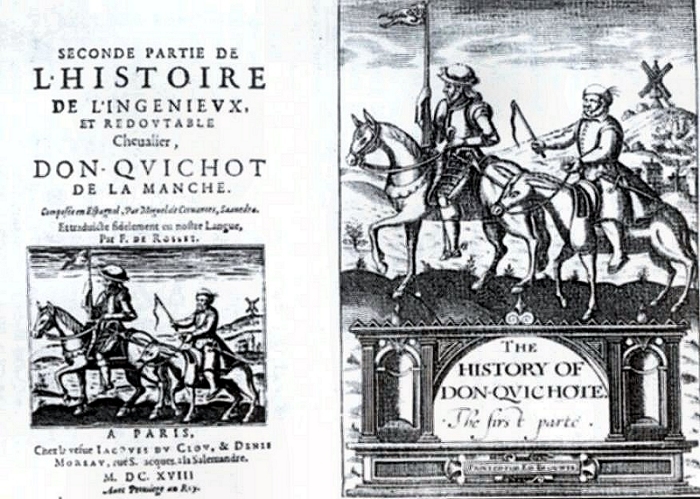

At the Segundo Coloquio de la Asociación de Cervantistas held at Alcalá de Henares, I had the pleasure of giving a paper in which were ventured some results of my studies on the first English editions of Don Quixote, 1612-1620. It was surprising to find several participants who were not convinced of the validity of the Gordon-Duff/Knowles dating (1620) of the second edition of Thomas Shelton's English translation of Don Quixote, Part I.129 This edition is particularly well known to bibliographers and iconographers because it bears an engraved title with an illustration which has been -and still is, we are constantly reminded- considered by —100→ some to be the first known of Cervantes's characters, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. The vignette which appeared on the title-page of François de Rosset's French translation of Part II, Paris 1618, seemingly a replica of the London illustration, has therefore been and still is thought by the same critics to be a copy, with the undated English edition in question the original, having been published, they assume, in 1618 or earlier (Figure 1a and 1b).

As I left Spain I purchased the latest Planeta paperback reprint (Nov. 1988) of Martín de Riquer's Quijote on the cover of which appears the London engraved illustration in question -tinted- with a title page verso notation which reads: «Ilustración cubierta: grabado de la primera edición inglesa, 1612.» If the Gordon-Duff/Knowles dating of the second edition of the English Part I given as 1620 is correct, then this statement, along with the many others mentioned in my paper, is doubly in error and exemplifies the manner in which the dating problem of the first and second editions of Shelton's Quixote continues to confuse and plague us to this day.

The first English edition of Part I, dated 1612, did not have an engraved title, but a printed title with no illustration.130 The second English edition of Part I with the illustration, though undated, according to the very convincing arguments of Gordon-Duff and Knowles, appeared in 1620, after the Paris 1618. The Paris vignette is therefore, according to these two authorities, the original, and the London, the copy. Since I have taken a stand conforming to that of Gordon-Duff and Knowles both at the Colloquium to which I have referred and in an article entitled «More on the sadness of Don Quixote: the first known Quixote illustration, Paris 1618», (Cervantes, IX, 1 [Spring, 1989], 75-83), I feel obliged to present this reassessment of the dating problem in question, trusting that a more studied and detailed account will further help clarify the issue.131

—101→

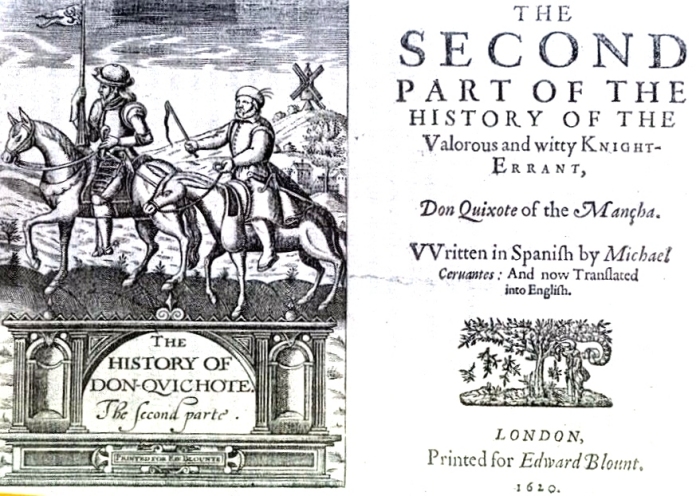

The Gordon-Duff thesis depends upon three main points: 1)The undated second edition of Shelton's Part I bears an engraved, illustrated title-page in its first state with a colophon which reads The first parte. This was determined by noting that all traces of the word first were not obliterated (namely, part of the loop of the letter «t») when the engraver cut second in its place; 2) All of the copies of the first edition of the Shelton Part II have a printed title-page, dated, while a good number of the copies of this edition have an added engraved title-page, the same as that which appeared in the second Part I, but now in its second state, reading The second parte (Figure 2a and 2b); 3) The conclusion drawn by Gordon-Duff in noting the existence of these two issues of Part II was that Blount, the publisher, in 1620 was already having printed the first edition of Part II when he decided to do a reprint of Part I. For this reprint he ordered prepared the above mentioned engraving with the illustration which in its first state read The first parte. When enough copies of this engraved title-page had been struck to accommodate all the copies of the new Part I, he then had the copper plate changed to its second state reading The second parte. By this time some copies of Part II had already been sold, which accounts for their not having the engraved title. Blount then struck enough of the engraved title pages in the second state to be bound to those copies of the Part II which already contained the dated printed title and which had not yet been sold. The undated Part I with the engraved title therefore appeared after the copies of the first issue of Part II dated 1620 were sold and along with those copies of Part II which had not yet been sold. This will have taken place in the year 1620 or later.

—103→

Gordon-Duff's reasoning is very logical, and difficult, if not impossible, I have learned, to refute. My reason for trying to do so was that I had attempted early on to determine the identity of the engraver of the English title-page which I, too, had supposed to be the first known illustration of DQ and Sancho. After discovering there was doubt about this, and after learning that I had spent a great deal of time in identifying not the «first» but the «second» engraver who had merely copied the French vignette, I was naturally hoping to be able to disprove the Gordon-Duff thesis. My efforts in the end were in vain, and the truth is that, at least in my mind, I only succeeded in strengthening Gordon-Duff's conclusions. If, as some contended, the undated second Part I appeared in 1618 or earlier, why would only a portion of the first edition of Part II contain both the printed and the engraved title-pages? Why would the engraved titles not appear in all the copies of the edition? There would have been plenty of time -some two years, in fact, if the book had been published in 1618 or earlier, as some contend- to supply all the copies with the engraved title. Also, the format of the colophon had been predetermined, I thought, because space had been left after the word «first» to make room for the word «second». If the engraved title-page to the second part had been prepared first -and one can suppose that it could have been- then all the copies of Part II should have had the engraved title, and traces of the word «second» should have appeared over the word «first», at least in some of the copies. Another point I considered in favor of the almost simultaneous appearance of the two editions was that Blount -who had George Purslowe print the first edition of Part II- had turned to another printer, William Stansby (who had done the 1612 edition of Part I) to do the reprint of Part I, evidently, even as Purslowe was still printing Part II. This was probably done in order that both parts might be readied and sold together.132 Many copies existed in which the two editions were bound together, but it was difficult to ascertain just when —105→ the binding had been done. Also, Stansby was probably the printer who would have provided the engraving.

To the conclusions of Gordon-Duff, repeated by Knowles and reported by me in my paper at the Colloquium, I added several of my own observations, not believing at all that Gordon-Duff's conclusions required support. I pointed out that in the printed and dated title-page to Part II Don Quixote's name is spelled with an «x» while in the undated engraved title accompanying the printed title (only in some of the copies, it must be reiterated) the name is spelled with a «ch». Since the «x» was placed on the manuscript by the translator, it would seem that the artist-engraver, apparently not having the manuscript or the printed title in his possession, simply took the name as it appeared on the French vignette which, one can assume, he was copying. I also suggested that the extraordinary, sad face of Don Quixote -which appears on the French vignette and is not at all reproduced or matched in the English engraving- would seem to have come first, the probable result of instructions given by de Rosset, the translator, to his engraver. It seemed unlikely to me that this face had been copied from the English illustration.

Despite the various points made, and though the «x» versus the «ch» anomaly was thought to be a good point, several participants, including Professor Casasayas, remained unconvinced, taking the stand that the countryside and accoutrements in the London illustration were -or at least were said to be- typically English, implying, of course, that the drawing had indeed been done by an English engraver in England, and so must have preceded the French vignette of 1618, a copy. This was, apparently, the principal argument which had to be addressed.

It appears that the bibliographer who has been most influential in proposing the English authorship of the engraving in question is Juan Givanel Mas, a former curator of the Colección Cervantina of the Biblioteca Central de Barcelona, compiler of the catalogues of that collection issued in 1916-25 in Catalan and 1941 in Castilian. In the Castilian version of the catalogue Givanel Mas had this to say about the undated edition of Shelton's Part I:

| (I, 71-72).133 | ||

Givanel Mas, greatly influenced by these comments by Pellicer, five years later in another book, Historia gráfica de Cervantes y del Quijote, elaborated upon these same ideas:

| (95-96). | ||

—107→

Pellicer, who frankly admitted one might attribute his statement

about similarities in the drawing between Don Quixote and Sancho and

Shakespeare and John Bull to a «sugestión

involuntaria» or to «propósitos preconcebidos» at least

seems to have had some reason to lean in this direction. In his article,

«Las ilustraciones del

Quijote», (La

Ilustración Artística, Barcelona, 1895, XIV, num. 680,

21-28) he indicates, with reference to what we know to be the second edition of

Part I, that he was dealing with what he thought was the

first known edition:

«... Hasta que aparece en 1620 y en

Londres con la

primera edición inglesa el

primer grabado representando a D. Quijote y a Sancho...»

(22). He then follows with the remarks which were

later to be quoted by Givanel Mas. Pellicer was taking for granted that the

date of this edition -which contains what he was calling the first known

illustration of Don Quixote and Sancho-

was 1620. Apparently he did not know of the

earlier Paris 1618 in which the same illustration appeared. If he had, he

probably would not have leaped, as he did, to the conclusion he expresses.

Under these circumstances he would have had to declare the 1618 drawing the

first and would have had to change his statement about whom Don Quijote or

Sancho resembled. Givanel Mas had less reason than Pellicer to come to the

conclusion that the English engraving was the first: he

knew of the Paris 1618 edition, but he was

apparently still so convinced that the English edition had preceded the French,

he readily assumed, borrowing heavily on the comments of Pellicer, that the

landscape and accoutrements in the English edition were, in fact, English.

Though he made a valid comparison between the landscape of Scotland or Wales

with that of La Mancha, not at all alike, he failed to make the more called for

comparison between the landscape of England and that of northern France, very

much alike, which surely would have led to a different assumption.

Because of the foregoing, and as part of the endeavour of

reassessment, I have attempted to determine in a more positive way the

«nationality» of the landscape and accoutrements as presented in

the disputed illustration. The landscape, as suggested above, cannot be

exclusively English or French, though it is not that of La Mancha. The

countryside -the grasses, the trees, the hills, the skies, the buildings- can

simply be either that of England

or France. The wind mill, perched on top of

the hill, is called an open or close post mill, and was common at the

—108→

time to both England and France.134 Sancho's costume

-according to Prof. Roberta Owen, a specialist in costume design of the

Department of Dramatic Art at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill-

is indeterminate, being a general type worn commonly in England and elsewhere

in Europe. Professor Heather Kelly of the History of Dress Department of the

Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, has responded to my questions

in this way: «

You are quite right in saying that the costume worn by Sancho

cannot be ascribed to any particular country; it is as you say, a kind of

'generic' garment, consisting of a long-skirted travelling coat, over the small

turned-down collar of c.1620. It could be Spanish, French, English, central

European...

»135 Mr. Ian Eaves, an armourial

expert from the Royal Armouries at the Tower of London, writes the following

with respect to the armour depicted: «

I am afraid that the standard of draughtsmanship exhibited by

the engraver is so poor that any meaningful interpretation of the armour is

impossible... it would be hopeless to see... any particular national style.

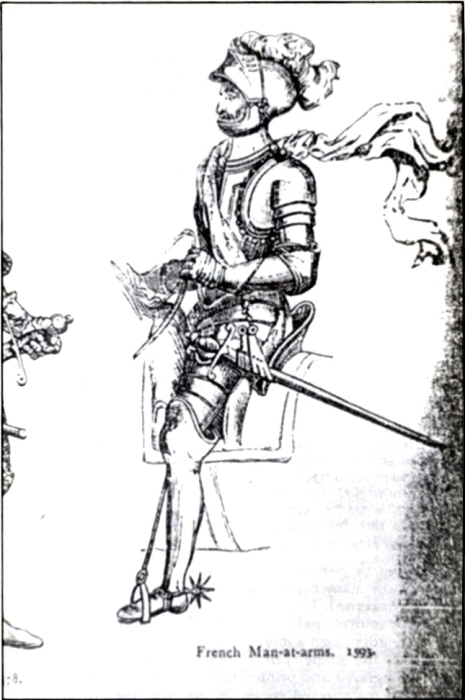

»136 With respect to Don

Quixote's dress, I myself have found armour somewhat similar to that worn by

him on a 1612 engraving of Joan of Arc drawn by the French illustrator, Leonard

Gaultier (Figure 3).137 Also I have noted that

the swords and sword attachments worn by Don Quixote and Sancho do somewhat

resemble those worn by a French man-at-arms of the year 1593

(Figure 4).138 It would appear that neither the landscape nor the accoutrements of the engraving in question, in the opinion of the mentioned costume and armourial experts, then, can be determined definitely as English or French, though the armourial accoutrements in my view could seem to be derived from the French. In any case, one cannot use with any validity either the landscape or the accoutrements in the illustration in an argument which would positively claim an English background to the engraving. Sancho as John Bull or Henry VIII can simply be attributed, as Pellicer hesitatingly admitted, to preconceived imaginings -propósitos preconcebidos. With the argument of English background considerably weakened, much doubt can naturally be cast on the confident assumption that the English edition with the engraving preceded the Paris of 1618. There remains, then, along with a few other observations, a review of the crucial points made by Gordon-Duff to determine if they can indeed be substantiated.

Knowles in his article «The first and second editions of Shelton's Don Quixote, Part I: a Collation and dating» (Hispanic Review, IX [1941]: 252-265), borrows his information from the rare Gordon-Duff pamphlet. After describing the order in which the plates for the reprint of Part I and the first edition of Part II were engraved, Knowles states:

(my italics)

| (265). | ||

In order to corroborate this information and also to determine in how many copies the loop discovered by Gordon-Duff could be discerned, I have checked some twenty libraries along with other sources, possessors of twenty-nine copies of the 1620 Part II, in order to get a more definitive idea of how many copies do contain the single, printed title against those which have both the engraved and printed title. Results of my survey show that ten of the checked copies do not have the engraved title-page

—111→

while nineteen do.139 From these results one can surmise that approximately one third of the copies were sold before the additional title was attached. Though more copies could be found for checking and though the proportion could differ, the fact remains that the edition did appear with and without the engraved title. The assumptions of Gordon-Duff and Knowles must be considered correct: the first edition of Part II, dated 1620, does indeed come in two issues: That issue with the dated printed title only came first; The reprint of Part I with the engraved title has to have come next, followed closely by or along with the second issue of Part II with both the engraved and printed titles.

In my survey, of the nineteen copies containing the engraved

title, only

five were reported to contain what was

considered to be the unerased portion of the loop of the «t» from

the word

first, discovered by Gordon-Duff. Both

Gordon-Duff and Knowles seemed to imply that the unerased portion of the loop

was generally visible, but this, obviously, is not so. Mr. Thomas V Lange,

Associate Curator for Early Printed Books at the Huntington Library of

California, in responding to my inquiries has suggested «

that the ghost image of the phrase 'The first parte' would

continue to appear on the first few dozen impressions after the new text had

been added

». The appearance of such ghost images is perfectly

common in corrected or altered plates, and

—113→

gradually faded with

continuous printing.140

This seems perfectly logical and would mean that very few copies would exist

today with what Gordon-Duff and Knowles called the unerased portion of the

«t». Because of the rarity of this ghost image, Gordon-Duff was

extremely fortunate to have happened upon a copy which contained a viewable

image.141 Early bibliographers, some of whom

may not even have seen or known of the 1620 Part II

with the engraved title, were thus rarely in

a position to make the same discovery and to determine correctly the chronology

of the editions in dispute.

The material in the foregoing discussion would seem adequate enough to prove the validity of the Gordon-Duff/Knowles thesis. However, other bits and pieces can be added to strengthen the case still more. More can be said, for example, about the spelling of Don Quixote's name in the two titles. As has been pointed out above, the engraved title spells Don Quixote with a «ch» while the printed title spells the name with an «x». When Blount registered Part I with the Company of Stationers of London on January 19, 1611, he gave to the wardens the title The delightful history of the witty knighte Don Quishote, spelling Don Quixote's name as it was being pronounced in England at the time, that is, with a «sh». Our engraver, if he had cut the name as it was being pronounced, should then have used «sh». The printed title, made from the translator's manuscript, properly uses «x» as it appears in the original. The engraver, if he had seen either the manuscript or the printed title-page, would have used an «x», as well. The only way he could have chosen «ch», which would not fit the English pronunciation of the time, is by having seen it on the French title of Paris, 1618. Along with this, in his dedication to Buckingham in Part II of 1620, Blount indicates his familiarity with the Paris 1618 edition.142 He probably had it in hand, turning it over to his engraver with instructions to copy the vignette on the title. Blount would hardly have —114→ reprinted Part I without having Part II in his hands, since it is likely he would have wanted to issue and sell both parts at the same time.

Another of Gordon-Duff's statements is useful for the

reassessment of the dating problem. He writes: «

The second edition of the First Part for which the engraving was

made was printed by William Stansby, and about 1620, in the books which he

printed, the engraved titles were the work of Simon Passe or of Renold

Elstrack, so that it is probable that this engraving is the work of one or the

other.

»

(12) In my talk at the Colloquium I also mentioned

Elstrack as the probable engraver, and in my book,

Essays on the periphery of the Quixote, being

published in 1991 by Juan de la Cuesta, I have included an essay entitled

«Renold Elstrack as the probable engraver of the title-page to Thomas

Shelton's

Don Quixote de la Mancha, 1620.» My

study concludes that William Hole, an engraver who had worked steadily for

Stansby for some years, left Stansby's employ in 1618 at which time he became

chief engraver of the English Mint. Evidence shows that Simon Passe and then

Elstrack took over. Quoting from my essay: «

In that year (1619), there is sufficient evidence to believe,

Elstrack engraved on behalf of Stansby the title-page to Drayton's

Poems. In 1620 he made up a new title-page

for Lodge's

Seneca as well as the title-page for

Hieron's

Workes (which comes in two states), and it

is likely in the same year he engraved the title-page for Thomas Shelton's

translation of

Don Quixote.

» The likelihood that Elstrack engraved the title in

question in 1620 or even a year earlier adds another minor point in favor of

the Gordon-Duff chronology. Yet another of Gordon-Duff's declarations can be

applied: «

From the altered plate more title-pages were struck off and

added to such copies of the Second Part as still remained unsold. This accounts

for the absence of this 'second' engraved title in so many copies.

In the case of the standard copies supplied by

the Stationer's Company to the Bodleian Library the reprinted First Part has

the engraving, while the Second Part has not»

(italics mine).

(12) As stated above, the first issue of the 1620 Part

II (without the engraved title) has to have appeared before the undated Part I

and the second issue of the dated Part II, both with the engraved titles.

Gordon Duff's comment implies, it would seem, that Part II of 1620 was received

first by the Bodleian, and that Part I with the engraved title was received

afterward. Mr. Clyde Hurst, Head of Special Collections at the Bodleian, has

not been able to

—115→

verify this and asserts that the accession

records of the period are so sketchy and that it almost impossible to determine

exactly when books were received from the Stationers Company. Books came in

sheets, unbound, and then were bound to other books totally unrelated in theme

or chronology. The undated second edition to Shelton's first part is bound with

STC 15352 (1619), «which doesn't mean much as books were received in

sheets and could wait for several years before being bound -the second part of

Don Quixote (1620) is bound with books dated

1616 and 1617 (letter dated 30 March, 1990).» It is still worthy of note

that the Bodleian did receive the first issue of the 1620 II and not the second

which contains the engraved title. However the books are bound, the implication

is strong that the second edition of Part I with its engraved title-page

followed a short while later.

Still another point can be added in favor of the Gordon-Duff dating. The pennant which appears on the lance carried by Don Quixote has the figure of a lion rampant. This should not be considered a coincidence. It is probable that the Parisian artist drew this lion at the suggestion of the French translator of Part II, François de Rosset, a nobleman and dabbler in knight errantry, one who was the most likely to have been inclined to add this heraldic touch to the depiction of Don Quixote as the Knight of the Lions, the title the knight gives himself in II, 17. If the lion had been placed there by the English engraver, it would likely have to have been done during or after the English rendering of Part II which was done in 1619 or 1620. De Rosset's work will still have appeared one or two years earlier.

Lastly, in my attempts to determine the identities of the engravers of the Paris 1618 and London 1620 titles, I have carefully noted the manner in which the grasses have been drawn in that part of the illustration used by both artists. While the mannerism shown is that of Leonard Gaultier and one or two of his French contemporaries, it is not that of Renold Elstrack or any of his English contemporaries. I conclude, though this is another minor point indeed, that it is likely Gaultier or another of the Parisian artists (perhaps one of Gaultier's apprentices) who originally drew and cut the plate for the vignette of the Paris 1618 edition of Part II.

In summation: the Gordon-Duff chronology cannot logically be disputed and can stand alone in the determination of the 1620 date set by him and confirmed by Edwin Knowles for the undated edition of the London Don Quixote Part I. The dated Part II —116→ did appear in two issues in 1620, and evidently the undated Part I was sandwiched in between these two issues. Surveys positively indicate the existence of the two issues of Part II, and also show that the shadow image found in the second issue and used by Gordon-Duff is fairly rare. Early bibliographers and investigators may never have seen the second issue of Part II with the engraved title, and if they had seen one, they would have to have had the good fortune for it to contain the rare ghost image. The argument -or supposition- put forth by Pellicer and Givanel Mas as to the English background and accoutrements which appear in the disputed drawing is shown to be untenable. Givanel Mas, while making a valid, negative comparison between the landscapes of La Mancha and that of the drawing which he supposes could be of England or Wales, failed to make at the same time the positive comparison of the landscapes of England and northern France. Gordon-Duff's pointing to Blount's possession of the Paris 1618, his report that the Bodleian Library received from the Stationers Company the first issue of the London Part II without the engraved title-page and the second edition of Part I with the engraved title, and my indication of the probability that Elstrack was the engraver of the English title in 1620, all lends support to the Gordon-Duff chronology. Other points made such as the spelling of «Quixote» with a «ch», the lion rampant appearing on the pennant, and the grasses depicted in the manner of Gaultier add more support to the Gordon-Duff conclusion. Though some of these points may appear to be of slight significance, it must be noted that the one argument found and offered to support the contention of English authorship can truly be declared inconclusive. The conclusion at this point is fairly undeniable: The undated second edition of Part I, despite what has been said up to this time to the contrary, appeared in 1620, and the illustration used in its engraved title is a copy of the French vignette which appeared on the title-page of François de Rosset's translation of Part II of Paris, 1618.

—117→Beedell, Susan. Windmills. Vancouver: David & Charles, 1975.

Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de. The Historie of the Valorous and Wittie Knight-Errant, Don Quixote of the Mancha. Trans. Thomas Shelton. London: Ed. Blount and W. Barret, 1612.

_____. The Second Part of the History of the Valorous and Witty Knight errant Don Quixote of the Mancha. [Trans. Thomas Shelton?] London, Ed. Blount, 1620.

_____. Seconde Partie de L'Histoire de L'Ingénieux et Redoutable Chevalier, Don-Quichot de la Manche. Trans. François de Rosset. Paris: Chez la vefue Iaques Dv Cloy, & Denis Moreav, 1618.

_____. El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha. Edición, introducción y notas de Martín de Riquer. Barcelona: Editorial Planeta, 1988 (reprint).

Encyclopedia Britannica. London: William Benton, 1963.

Ewing, Elizabeth. Everyday Dress 1650-1900. London: B. T. Batsford, Ltd., 1984.

Givanel Mas, Juan, ed. Cataleg de la Collecció Cervántica formada per D. Isidro Bonsoms i Sicart, cedida per ell a la Biblioteca de Catalunya. 3 vols. Barcelona: Institut 'Estudis Catalans, 1916.

_____. Catálogo de la Colección Cervantina. 4 vols. Barcelona: Biblioteca Central, 1941.

_____ y Gaziel. Historia gráfica de Cervantes y del Quijote. Madrid: Editorial Plus-Ultra, 1946.

Gordon-Duff, E. Notes on the hitherto undescribed First Edition of Shelton's translation of «Don Quixote», 1612-1620. London: p.p., n. d. (1916).

Hartau, Johannes. Don Quijote in der Kunst. Berlin: Gebr. verlag, 1987.

—118→Knowles, Edwin Blackwell. «The First and Second Editions of Shelton's Don Quixote, Part I: A Collation and Dating.» Hispanic Review, 9 (1941) 252-265.

Laver, James. Costume of the Western World -The Tudors to Louis XIII. London: George Harrap & Co.

Lo Ré, Anthony G. «More on the sadness of Don Quixote: the first known Quixote illustration, Paris 1618.» Cervantes, 9, 1 (Spring, 1989), 75-83.

_____. Essays on the periphery of 'Don Quixote'. Newark, Dela.: Juan de la Cuesta, 1991.

Pellicer, J. L. «Las ilustraciones del Quijote.» Barcelona: La Ilustración Artística, XIV, num. 680, 21-28.

Reynolds, John. Windmills and Watermills. New York-Washington: Praeger Publishers, 1972.

Vecellio, Cesare. Renaissance Costume Book. New York: Dover Publications, 1977.

Watts, H. E. «Translations of Don Quixote.» Notes and Queries. 8th ser, Nov. 18, 1893, 402-3.