Some aspects of Spanish book-production in the Golden Age

Don William Cruickshank

(A paper read before the Bibliographical Society on 15 April 1975)

In 1925, they say, Spanish roads were among the best in Europe. Complacent in their superiority, the Spaniards neglected their roads, with results familiar to anyone who has motored in Spain. Spanish bibliography is not unlike Spanish roads: in 1925 it did not suffer unduly from comparison with bibliographical studies elsewhere in Europe. Since then it has fallen behind. The Civil War and its long aftermath are partly to blame. A few scholars like the late Don Antonio Rodríguez-Moñino maintained an interest in the subject, and thanks to him and to others, Spanish bibliography is at last showing signs of emerging from its long dark tunnel. We should be glad. But as the emergence takes place, we can see clearly that the bibliographical cart is preceding the bibliographical horse.

The most recent and striking example of this phenomenon of mistaken priorities is the catalogue of seventeenth-century Spanish and Portuguese books in the British Museum, published by Dawsons1. The seventeenth century is arguably the most important in Spanish bibliography as far as subject-matter is concerned, so it is particularly disappointing to find that this catalogue has virtually no analytical basis; it simply reproduces, in short-title form, the entries in the General Catalogue2. Another major example is the work of Don José Simón Díaz, Professor of Bibliography at Madrid University. The most important of his numerous works is his Bibliografía de la literatura hispánica, now at letter G, which puts into practice the theories set out in his book on the concepts and applications of bibliography3. For him, bibliography is a descriptive science; he says nothing about the analysis of books. His Bibliografía is like the Dawson catalogue: a list of books taken, in the main, at their face value. The Palau catalogue, now nearing completion, is similar, although it would be unfair to criticize it, given its more limited aims, for lacking an analytical basis4. The point is, however, that scholars who rely on these catalogues for information on the Spanish book trade, or on Spanish literary history, will be misled by them into producing a distorted picture.

The danger lies in taking Spanish books of the hand-press era, and especially of the Golden Age, at their face value. Spanish printing was influenced by a number of factors which combined to create its unique quality: the geographical position of Spain, availability of skilled labour, economic conditions, censorship, and public demand.

When Antonio de Nebrija dedicated his Spanish grammar -the first vernacular grammar in Europe- to Queen Isabella in 1492, he said that language went always hand-in-hand with empire5. As a result of other momentous events of that year, Spanish printers had to serve the largest reading public in the world. In the sixteenth century, as the empire expanded, they had few worries about lack of demand for their work; in the seventeenth century, when expansion ceased, the number of printers and booksellers outstripped demand, causing more intense competition6. At the same time, Spanish printers formed part of an industry in which standards generally were in decline, thanks, as Gaskell has pointed out, to this very factor of intense competition7. Moreover, they had to contend with an economic situation which was worse in Spain than elsewhere: shortage of skilled labour, serious inflation, and the consequent lack of investment in industry8. The industries which produced the printers' basic materialspaper and type-were coping unsuccessfully with the same problems, and the printers had either to use the poor (and scarce) material made in Spain, or import expensive material from abroad.

These difficulties were aggravated by a bureaucratic licensing system. Books needed two licences, civil and religious, each involving two bodies: the officials who conceded the licence, and the qualified persons to whom they sent the manuscript for vetting. Later His Majesty's Corrector checked that the printed book corresponded with the manuscript (or previous edition), and His Majesty's Council fixed the price. If he thought it worthwhile, the printer (or author) could apply for a ten-year privilege, which had to be signed by His Majesty in person. All this tied up capital for even longer, and ate away profits in fees and complimentary copies. Sometimes distribution was delayed while theologians debated-too late-points of doubtful orthodoxy. Occasionally an edition was suppressed completely9.

The combined result of all these factors was a greater decline in standards than in most European countries; and the lowering of standards in order to compete was aggravated by the use of poor materials. As for the shortage of capital and skilled labour, they were forced to overcome that by pooling resources: sometimes lending materials, more often sharing the work; or, in the case of publishers, sharing the cost. Thus a single book might be financed by two publishers, who supplied different kinds of paper, and printed by several printers, each of whom used his own type10. Shortage of type was overcome by setting by formes, which persisted longer in Spain than elsewhere (setting by formes requires casting off, which any numerate person could do well enough to satisfy the prevailing standards; setting by pages needs more type, but is cheaper in the long run)11.

These irregular methods of producing lawful books made the detection of fraudulent ones almost impossible. The commonest fraud was a reprint of a lawfully produced best-seller. Since the public (and the authorities) were used to editions with obviously different states, they had little cause to suspect a falsely dated illegal reprint for what it was. No doubt the public did not mind, except in cases like Calderón's Primera parte of «1640», where they paid for 75 sheets and got 65, minus some text12.

The printers were also helped to overcome the regulations by the nature of the public's demand. Spanish Golden Age literature had strong popular traditions behind it, and retained its popular appeal more than was the case in almost any other country. The «lowbrow» Spanish public of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries could take undiluted small doses of major authors: poems of Lope de Vega, Góngora, Quevedo; plays of Lope, Tirso de Molina, and Calderón. So there was a great demand for ephemeral editions of the work of these authors in the form of single plays, or chapbooks containing scenes of plays and poems. Large quantities of less «literary» work were also printed13. It came to be accepted that reprinted work of this kind need not carry all the documents prescribed by law for printed books; but at first the printers seem to have avoided the problem by omitting the imprint, and by distributing the work through «unofficial» channels: street-traders and «walking stationers». Some plays were so printed that they could be bound in dozens, with the legal preliminaries, or sold singly, with no printing details attached. Spanish has a word for this, desglosable, which we can only render as «disbindable».

These different practices current in the Spanish book trade result in three specific problems for Spanish bibliographers: one, the lawful book produced by work-sharing among printers, only one of whom puts his name in the imprint, which is therefore innocently misleading; two, the falsely dated reprint (also subject to work-sharing); three, the imprintless book. None of these problems is peculiar to Spain, but I suspect that their combined effect is greater there than elsewhere (the merely imprintless Spanish books in the Dawson catalogue account for over a third). So if these problems are disregarded, as they generally have been, they seriously distort the picture of Spanish book-production14.

At present we have no efficient way of solving the problems. Faced with an imprint which seems misleading, or with no imprint at all, we can make a guess about date and place and then examine books of that date and place in the hope of finding the same ornaments and type. If the guess is good, the process thereafter is satisfactory. The comparatively wide range of types employed by Spanish printers, and the adulterated state in which they often used them, enable us to identify a printer's unsigned work with confidence (if enough signed material is at hand). The unsatisfactory part of the process is the imprecise initial guess15. To improve it, we need to know far more than at present about all aspects of Spanish book-production, starting with the most basic: the manufacture and distribution of the type used in Spain from about 1560 to 1700 (I omit the first half of the sixteenth century, partly to avoid the special problem of gothic type, partly because F. J. Norton has covered the first twenty years very thoroughly)16.

The typographer who examines Spanish books of this period will find much that is familiar: Granjon italics, Garamont romans, and, not surprisingly, given Spain's links with the Netherlands, the types of Guyot, Tavernier, and Van den Keere. But some types are unfamiliar, and familiar ones have been modified by means of recut letters, or are cast on unusual body sizes. The questions I should like to begin to answer are, where did these strange and modified typefaces come from, and will they permit us to distinguish and classify groups of Spanish books ?

I should like to begin with a Fleming called Matthew Gast, who printed and published in Salamanca from 1562 to 1577. I choose him because he corresponded with Plantin in 1574 about his difficulties in obtaining type17.

One of Gast's first books was Melchor Cano's De locis theologicis of 1563, an imposing folio which nevertheless reveals some of Gast's problems. There are eight romans, three italics, a greek, and some hebrew. The greek is Granjon's long primer, but Gast used it with an english roman of 96 mm./20 lines. The few hebrew words are printed from woodblocks, not metal type, since all recurring letters differ. By 1570 Gast had a proper hebrew fount, but he was still using his one greek face as english and long primer. His pica italic also served as english at this time18.

These adaptations

suggest that Gast had a small range of typefaces, and that he

extended the range by leading, or by casting from the same matrices

in moulds of different sizes. The woodblock hebrew suggests that he

had no craftsman able to cut punches and make matrices from them.

His 1574 letter to Plantin confirms this. He asks for complete sets

of matrices for two faces he has seen in Plantin's work, and adds

that he would account it a great favour if he could be sent

«a good typefounder; I say a good

typefounder because a bad typefounder will not do, for there are

plenty of those around here, but a good one who can justify

matrices and make moulds»

19.

Plantin's reply was friendly but evasive, and I have found no

evidence that Gast ever got the matrices that he asked

for20.

Gast was no provincial jobber, but a man praised by his contemporaries and recommended by Plantin for the post of royal printer in Spain21. Yet he was typical: even major printers owned or dealt in matrices, not punches. The only positive record of punch-owning in this period is the inventory (1572) of Claudi Bornat of Barcelona. Bornat had over 3,300 lb. of cast type and twenty-seven sets of matrices (impressive figures), but his only punches were for music and very modest: a mere twenty-five comprising both «grosa nota» and «petita nota». A comparable contemporary, Vicente de Millis of Medina, who in 1568 bought a large amount of material, apparently to set up as a printer, got 2,700 lb. of type and sixteen sets of matrices, but no punches22. In 1573 Francisco Sánchez of Madrid paid sixty ducats for five sets of matrices, each set with its mould23. In 1584 the new operating regulations drawn up for the press of San Pedro Mártir in Toledo, which printed indulgences, pointed out that the existing matrices were worn and that new ones must be bought. Once bought, they and their punches were to be kept on the premises24. A later document, which I shall refer to presently, shows that in 1633 the press again lacked matrices, and had to have them made in Valladolid from scratch (i. e., punches were made first). This suggests that the press failed to obtain punches in 158425. An inventory of 1595 shows that Pedro Madrigal, a major Madrid printer, had twenty-five sets of matrices, each with its mould, and that although some matrices were unjustified, he had no punches26. An inventory of the goods of Jaume Cendrat of Barcelona, who died in 1589, shows that he had five type-moulds and several sets of matrices, some of them on loan27. In 1607 Cosme Delgado of Valladolid borrowed two sets of great primer matrices (roman and italic) from Luis Sánchez of Madrid, promising to pay 100 ducats if he failed to return them28. That suggests that matrices had increased in value from an average of twelve to fifty ducats a set in thirty years.

Not surprisingly, there is evidence that smaller printers were unable to lay out capital of this kind. Instead, they owned and dealt in type, which they bought from typefounders or from other printers. Thus in 1603 Artus Taberniel (apparently a son of Ameet Tavernier who had hispanized his name) paid Cristóbal de Contreras, who was probably acting for Luis Sanchez, 572 reales, being the rest of what he owed for two presses and 25 ¼ arrobas of type (635 lb.)29. About this time Taberniel began printing in Salamanca, presumably with this very modest stock. Ten years later, an inventory of the goods of a more important printer, Miguel Serrano of Madrid, lists two presses and only 975 lb. of type. The greek type was enough for just one folio page; and although individual woodblocks are described, there is no mention of matrices or punches30. Clearly Serrano had none31.

As for the founders who supplied these printers, we know little more than their names. Don José-María Madurell quotes eight who worked in Barcelona between 1557 and 163932. The most important one, Hubert Gotard, who probably died in 1589, was also a printer. In his shop he had ten sets of matrices, five presses, and about sixteen founts of type. At home were another twenty-five sets of matrices. There is no mention of punches33. In 1579 he supplied a printer with 44,625 pieces of pica, about 180 lb. This size of order seems to have been a typical one in Spain in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but it is less than half the amount that French printers normally bought in the seventeenth century34.

Details concerning Madrid typefounders are similar. One, Claudio Bolán, was working in Madrid in the late 1590s35. Another, Juan Gotard (perhaps a relative of Hubert Gotard of Barcelona), was said to be 53 in May 1636, and died in May 1640. In February 1619, he agreed to supply Julián de la Iglesia, a Cuenca printer stated to be temporarily resident in Madrid, with «fifty thousand well-cast letters». He was to be paid four and a half reales per thousand for casting and one and a half reales per pound for metal36. A document of 1636 shows that he was asked to value the equipment of the printer Diego Flamenco, which had apparently lain unused since Flamenco died in 1631. This document tells us that he lived in rented accommodation37. He examined Flamenco's type and pronounced it fit only for the melting-pot; the value of the type as metal, at one and a half reales per pound, was 1,039 reales, which means that Flamenco had only 693 lb. of type. Eventually the whole stock, type, and material described as «the wooden things», was sold to a Madrid bookseller for 1,400 reales.

We know a little

more about Francisco de Robles, although there were three men of

this name in the book trade. The typefounder was active in Madrid

from at least 1596 until his death in 1616. In 1596 or 1597 he cast

1,856 reales'

worth of type specifically for printing Juan de Pineda's commentary

on Job. He was apparently paid by a colleague of the author, not by

the printer38.

In February 1603 the Seville printer Clemente Hidalgo informed an

author that he was ready to print a book «in great primer newly cast by Francisco de

Robles for the said book»

39.

The most interesting document is his contract made in 1605 with

Luis de la Vega, an author from Córdoba, to supply enough

brevier for three formes, reckoned as 60,000 pieces of type. This

was to be used by the Cordoban printer Ramos Bejarano to print

Vega's book40.

The cost was four-and-a-half reales per 1,000 for labour and one and a half

reales per

pound for metal, approximate total fifty ducats. From this we can

deduce that the amount of type was about 190 lb., and that the cost

of casting and the cost of metal each accounted for about half the

total.

Finally, there is a single reference to Francisco Calvo: in 1646, in Madrid, he cast 909 lb. of type for Antonio Sánchez of Salamanca. He allowed Sanchez one and a half reales per pound for his old metal, and charged four and a half per 1,000 for casting41.

These scraps of information give us a very limited view of typefounding in Spain, and it may be unwise to try to form a general picture from them. There are signs that none of the founders was very well-off. They regularly supplied type to provincial printers, who apparently came to them to get it. The orders were small, because the printers seldom had large stocks of type. On two occasions, the type was paid for by an author or his friend, not by the printer. In Madrid, one and a half reales per pound was the standard rate for type metal in the first half of the seventeenth century. The cost of casting type, at four and a half reales per thousand, was the same in 1646 as in 1605. In Barcelona, where the coinage differed, the price was also constant. In 1579 Hubert Gotard charged nine sueldos per 1,000 pieces of pica; sixty years later Joan Dexen got the same rate for an english roman42. The Barcelona sueldo was just under half a Castilian real, so if these charges refer only to labour, the cost was almost exactly the same in Barcelona as in Madrid.

One hesitates to base too much on these figures, but it is a fact that the average wage index in Castile rose nearly fifty per cent between 1600 and 1650. There was a similar rise in prices. Since the typefounders could not have held their prices down by increased productivity or improved technology, their position in the Spanish economy must have suffered a relative decline; the standard of their product certainly declined. As we shall see, they saved money by adapting and continuing to use old material which their more fastidious predecessors would have replaced.

The documentary evidence for punchcutting in seventeenth-century Spain is minimal. I suggested earlier that the press of San Pedro Mártir failed to obtain punches in 1584. The evidence for this is a letter written in 1633 by the Commissary General of the Santa Cruzada to the Monastery of Prado in Valladolid. The matrices of San Pedro Mártir were in need of replacement, and the Commissary had learned that only one man in all Spain could cut punches for a new set. The man was described as a foreigner, but another document calls him Marcos Orozco, silversmith of Valladolid, and indicates that he agreed to cut 265 steel punches and to make strikes from them43. Perhaps Orozco really was a foreigner who had hispanized his name. More important is the suggestion that he made punches only as a sideline.

So much for documentary sources. Other sources are of two kinds: contemporary references to type-manufacture in Spain, and the circumstantial evidence of the books themselves. I know of only three examples in the first category. The first is Cristóbal Suárez de Figueroa's Plaza universal de todas ciencias y artes, first published in Madrid in 1615. Suárez took the idea and some of his material from Tommaso Garzoni's Piazza universale di tutte le professioni del mondo; both of them deal very briefly with typemaking, but while Suárez omits Garzoni's brief reference to punchcutting, he says more about typefounding and the work of preparing cast letter for printing. And since his book was printed by Luis Sánchez, who certainly had matrices in 1607, his account probably reflects what could and could not have been seen in Madrid in the early seventeenth century44.

The second author

to describe Spanish typemaking is much more interesting than

Suárez. For one thing, his booklet was printed in 1675, in

the middle of the uninvestigated second half of the century;

secondly, he seems to have had a passionate interest in the book

trade: at least seven times, beginning in 1636, he petitioned the

king for the removal of taxes on books. His name is Melchor de

Cabrera Núñez de Guzmán, and the title of his

booklet is even longer, so I shall call it his Discurso45.

The passage on typefounding is too long to quote46.

It obviously owes nothing to Suárez, and must be the account

of a very interested eyewitness. He says nothing about punches. His

description of matrices is quite revealing: a matrix, he says,

«is a piece of bronze, very

small in form, in which is engraved the letter it is

desired to cast»

. I doubt if this means that the recent

suggestion of a Dutch authority is borne out by practice in

Spain47.

On the contrary, it clearly means that Cabrera never saw a punch

cut or a strike made: he saw only the finished matrix, and guessed

from its appearance at the method of manufacture.

Cabrera's Discurso was printed by Lucas Antonio de Bedmar, whose firm worked in Seville and then in Madrid from 1669 until at least 1717. Bedmar became a royal printer, held an honorary royal post, and seems in a small way to have been an author48. Not exactly an Estienne, but perhaps the nearest thing that Spain could produce at such a low ebb in her printing history. Surely, one might think, if any printer still cast his own type, it would be such a one. But there is no evidence that Cabrera saw type cast by Bedmar's workmen. On the contrary, a close examination of Bedmar's books shows that when a much-used type like pica wore out, it was replaced by a different pica fount. Partial replacement was more common than complete replacement, so that we find mixtures of two or even three different designs in a single page. The same was true of larger type: when Bedmar's son replaced his battered Granjon petit canon As about 1710 (A is the commonest letter in Spanish), he did so with a different design. This is why Bedmar's undated work can be dated with comparative ease. No printer (save Plantin) could have felt the need to own matrices for all the founts used by Bedmar's firm between 1669 and 1717. I have not examined the work of Bedmar's contemporaries in as much detail, but I suspect that the pattern is the same in most of them. This suggests that in seventeenth-century Spain the process of typecasting passed from even major printers to specialist founders-as it had done elsewhere in Europe rather earlier.

Many years after Cabrera's Discurso, in 1732, the Valencian printer Antonio Bordázar, who was trying to revive the Spanish type industry, said that during the reign of Charles II (1665-1700), matrices were obtained in Flanders for use in Spain. Bordázar came from an old printing family, so his information is probably reliable. He implied that these matrices had been in use in Madrid since their acquisition, and gave samples of type cast in them; but the faces are all old faithfuls, used in Madrid long before 1665, so they tell us little. He says nothing about punchcutting49.

The circumstantial evidence from the books themselves is more numerous and more difficult to assess. It contradicts what is implied by the three writers just quoted, in that it indicates that punches must have been cut in Spain right up to the end of the seventeenth century. Three authors stand out, two of them orthographical reformers. The first is Fernando de Herrera of Seville, the poet and editor of Garcilaso. Between 1572 and 1592 he produced four works which illustrated his reforms. The most noticeable feature in them is the lack of dots on i and j, but this seems to have been achieved by adapting cast type with a knife. A few special vowel punches must have been cut, however, and type made from them, but we cannot even guess at the identity of the craftsman50.

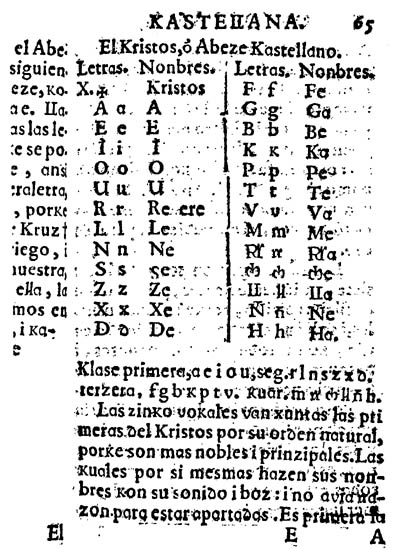

The most ambitious of Spain's early orthographical reformers was undoubtedly Gonzalo Correas. His Ortografia Kastellana was printed in 1630 by Jacinto Tabernier of Salamanca, and although only one typeface -Haultin's english roman- was adapted, as many as twenty-four new punches were cut for it, some of them quite unusual. Correas was a professor in Salamanca University, but his choice of printer may not be a question of geography. Jacinto Tabernier was almost certainly a descendant, probably a grandson, of Ameet Tavernier of Antwerp, one of the best punchcutters in the Low Countries. A number of competent copper engravings bear Jacinto's signature, so a combination of heredity and known engraving skill make him the most likely candidate for Correas's punchcutter. Marcos Orozco of Valladolid is another possibility51. The new alphabet is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Correas's proposed new alphabet, from p. 65 of his Ortografia Kastellana, showing most of the specially cut sorts. Original measures 115 (125) x 71-5 mm.

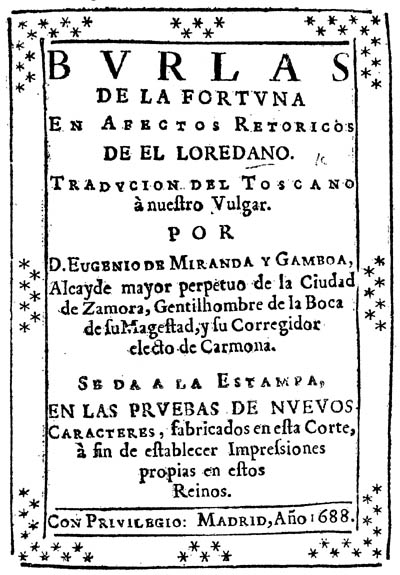

Fig. 2. The Loredano title-page, showing the 8 mm. titling capitals, and the caps, small caps, and lower case of the great primer. This and fig. 1 are reproduced by permission of the British Library.

The third work to

be discussed in this context is a very unusual one. The title is

Burlas de la

fortuna, a translation from the Italian of Giovanni

Francesco Loredano, and it was printed in Madrid in 1688 by an

anonymous printer52.

The subject-matter is irrelevant; what counts is the remark on the

titlepage, that it was printed to try out «new characters,

made in this capital city». The dedication, by a Don Eugenio

de Miranda, mentions his concern at Spanish wealth filling foreign

coffers (presumably a reference to imports of typographical

material), and that as a result of his concern «a great Craftsman offered to make in this

capital city all the instruments which give credit, esteem and

worth to foreign Impressions»

. The rest of the

preliminaries are just as infuriatingly vague. But various remarks

indicate that the craftsman concerned must have cut punches and

made a strike from them. So the book is ostensibly the first for

many years (but not the very first) to be printed entirely from

type made in Spain from scratch. The title-page is reproduced as

Fig. 2.

A hundred years after the event the punchcutter was named by Eugenio Larruga as Diego Dises, who was said to have come to Madrid in 1683 to work as a punchcutter, but without success owing to lack of financial support53. Where he came from is not stated, but Dises is not a Spanish name. The few Spanish bibliographers to notice the book have tended to denigrate the type; but whoever Dises was, he was not an inexperienced punchcutter, although the book contains only two founts: a set of two-line pica titling capitals, and a great primer with lower case, caps, and small caps. I have not seen the great primer in other books, but the titling capitals were used by at least thirteen Madrid firms between 1685 and 174454. Presumably Dises cut them soon after his alleged arrival in Madrid. I think he may also have cut a copy of Van den Keere's heavy gros canon capitals: this copy appears in Madrid books about 168655.

Before learning of the attribution to Dises I had formed a different theory about the identity of Miranda's craftsman, based on the fact that there is a series of morsels of circumstantial evidence for Spanish punchcutting long before 1683. There is no evidence of an industry, or of formal apprenticeships; rather that there continued to be people like Jacinto Tabernier or Marcos Orozco, silversmith, whose background and training were such as to enable them to cut punches if the need arose. These people produced replacements or adaptations for existing founts, occasionally the twenty-odd sorts of a set of titling capitals, but not the 130 punches that go to make up the average complete set56. I shall give some examples. I appreciate that in some of them the circumstantial evidence is not entirely reliable.

A late copy of Van den Keere's gros canon capitals has been mentioned. There was another, much earlier copy, used as early as 1587, in Salamanca. During the following century it was used all over Spain, but especially in the Madrid area. It may be foreign, but there is no evidence that it is.

Another apparently Spanish copy is of the 13 mm. capitals of the Vatican specimen of 1628. The originals were popular in Spain from as early as 1621, well before the publication of the specimen. The copy appeared in Madrid in the 1680s. For all I know it was cut by Dises: the cutter was faithful enough to the original to disguise his identity.

Apart from copies, there were adaptations. Special adaptations made for orthographers have already been mentioned. There were also more prosaic ones, made for thrifty printers in the manner given currency by Plantin. Prior to 1683 there were at least four different attempts to adapt english romans to pica bodies by means of recut descenders. Three of them involved Garamont's english roman, the fourth an old english roman which had been popular in Madrid about 160057. Italics, mostly Granjon's first and second St. Augustines, were adapted to match, but not by recutting: instead, they mixed pica matrices of long letters with the rest of the St. Augustine sets. On some occasions they must have adapted matrices or moulds in order to cast descender letters high on their bodies, thereby avoiding kerning. On one occasion a founder reduced Granjon's first St. Augustine to 84 mm./20 lines by vertical kerning, as distinct from the horizontal kerning which is normal in italic faces58. The least ambitious adaptations involved upper-case J and U, which appeared in Madrid printing about 1690. Perhaps their appearance was triggered by Dises, whose liking for them may be further evidence of his foreign origin, or at least training. At any rate the old faces in use in Madrid at this time, and which had never had these letters, now acquired them. Some of the Js and Us may be imported, but others are so bad that one feels they must be Spanish.

Finally, there were replacements for lost matrices. These are almost too numerous to count. In some cases the replacements were probably borrowed from other sets of different design, but in one case at least this did not happen. The face involved was Granjon's gros cicéro. Between 1664 and 1676 most printers in Madrid (and one or two in Seville and Málaga) used this face with a striking double-dotted j. One might put it down to some absurd fashion, were it not that some Madrid printers later used the face with a different, but still not original, j. Evidently two j-punches, one of them rather eccentric, were cut to replace a lost matrix. The eccentricity did spread, however, to one other face, Haultin's english roman, which also enjoyed a double-dotted j for a year or two59.

My suggested punchcutter for at least some of these new punches is the Marcos Orozco who engraved more than twenty copper plates in Madrid between 1660 and 169960. This can hardly be the original silversmith of 1633, but since he appears to have been friendly with some Valladolid calligraphers (as well as being a calligrapher in his own right), he must be a son, or at least a nephew of the other61. There is no proof that he ever cut a punch, but his name can be added to the list of those who, by background and known skills, were fitted to cut punches if the need arose.

If all this makes the seventeenth-century Spanish type industry sound very improvised, then so it should. In the sixteenth century most major printing cities had local sources of type, often the printers themselves. The general European trend for a few specialist founders to take over from more numerous printers received an unhealthy impetus in Spain from the contraction of the book-trade as a whole. In Madrid this contraction began in 1624, and everywhere typefounding declined, often to extinction, certainly to the point where the founders were hard put to supply even the diminished needs of the printers62. I know of only one documentary reference to a typefounder in Seville, in 1550. The document exists only because the founder agreed in it to emigrate, with an assistant, to Mexico63. Fifty years later, as we have seen, Seville printers were buying type from Madrid. By 1680 Madrid was supplying all Castile with type, and trying desperately to find the matrices to do so. At the same time Barcelona was the chief source of supply for Aragón, and Aragonese books generally display a different range of typefaces from those of Castile. In both Castile and Aragón we find ancient, once discarded faces being revived, as if founders had scavenged through old stocks of matrices.

Transport costs in Spain were high (not to mention internal customs dues), and printers in Seville, fortunate to live in a great port, apparently found it as cheap to import type from the Netherlands64. As far as I know, they were the only printers in Spain to use Guyot's pica roman (one of his less popular faces), «De Laet's» small pica italic (rare anywhere), Jannon's great primer italic, and, as the century advanced, a whole range of faces associated with the Dutch foundries of Van Dyck and Voskens65. They were the first, and with one exception, the only printers anywhere to obtain Granjon's ascendonica italic, long supposed to have been jealously guarded by the Plantin-Moretus family66.

Obviously then, specific areas in Spanish printing are marked by different sources of type. As sources became fewer, the areas grew larger. The evidence is always complicated by migratory printers who carried type with them, or by printers who obtained type from further afield than usual, prompted and paid by authors or publishers. One example of this is Ruiz de Murga of Madrid, who printed Calderón's Autos of 1717 in type bought in Holland for the purpose, although type could have been obtained in Madrid67.

Some typefaces are almost useless as evidence because of widespread use in both place and time: Granjon's petit canon and paragon italic, and Garamont's paragon and great primer romans are among these. Others enjoyed widespread use for a limited time, and can help in rough dating. One such is Garamont's gros canon, which had disappeared from general use in Spain by 1640; the capitals remained longer than the lower case, and were used for titling. They were gradually overtaken in the Madrid area by the early copy of Van den Keere's gros canon capitals, and throughout Spain by the 13 mm. Vatican capitals68. Two italics, Granjon's third St. Augustine and Tavernier's pica, popular in Madrid in the early seventeenth century, also disappear69. They were replaced by an italic possibly cut in Rome, and which served as english and pica70.

A similar example is Haultin's médiane italique grasse, used extensively in Aragonese cities throughout the seventeenth century, but in Madrid only rarely, especially in its pure form71. Aragonese printers also used Haultin's pica roman, which seems never to have reached Madrid, and a set of 8 mm. titling capitals, very rare outside Aragón72.

The conclusions derived from these examples, and from others too boring to list, are provisional, and permit only rough classifications to be made. But the general conclusions are compiled from particulars involving single printers. The more evidence one gathers for the general picture, the nearer one gets to a type-repertoire for every printer in seventeenth-century Spain. Which is to say that the problems of Golden-Age Spanish bibliography are quite soluble. The process of solution requires only some effort, and a lot of time.

If this process requires further justification, it can be found in two recent lectures given by eminent hispanists: that of Don Antonio Rodriguez-Moñino in New York in 1963, and the Taylorian Lecture of Professor E. M. Wilson in 196673. These lectures show that literary critics have failed to take full account of the current literature of Golden Age Spain. Some of the works which we regard as very influential, and for which the resulting intensive study has produced much bibliographical documentation, made little impact on their contemporaries. Much of the material which produced the literary formation of Golden Age Spaniards was ephemeral (and imprintless) or is now neglected. For example, St. Teresa confessed in her autobiography that her mis-spent youth included the reading of chivalresque novels (some traces have been found in her prose)74; the late Professor Jones has pointed out that the abdication of Charles V, so extraordinary in 1556, has an excellent precedent in the chivalresque novel75. Professor Wilson has shown that one of Calderón's best-known plays had its origin in a popular tale76. But we rarely study chivalresque novels now, believing erroneously that they were never reprinted after Cervantes squashed them in 1605; and the bibliography of Spanish popular literature is in disarray.

The intellectual decline of Spain in the seventeenth century is still imperfectly understood, as is its connection with the economic collapse. As regards that collapse, historians have recently become aware that it has a previously unimagined complexity of causes. An important aspect of the collapse, the slump in the book trade, has not been studied. A superficial glance at the statistics of the slump suggests that it coincides, both in particular local instances and in general, with Spain's literary decline; «obviously», one may say, but the nature of the coincidence is less obvious77. Clearly, then, if we are to have a full knowledge of the literary and economic background of the writers and statesmen of Golden Age Spain, we must study the history of book-production. And our study must begin at the beginning, with the bibliographical examination of the books themselves, so that we know what was available to be read, and when78.