Some Notes on the Printing of Plays in Seventeenth-Century Seville

Don William Cruickshank

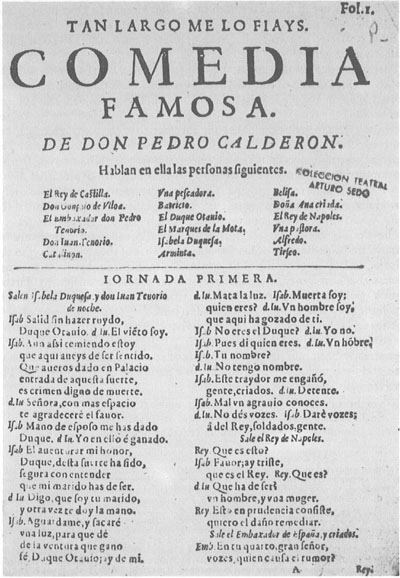

The study which follows arose out of curiosity about the printer of the first known edition of Tan largo me lo fiais. Tan largo survives in a nondescript suelta, with neither date nor imprint, which ascribes the play to Calderón1. Identifying the printer of such an item is not a simple task, but one may begin with the hypothesis that a printer who printed one play may well have printed others. It is reasonable, in other words, to start looking for the typographical characteristics of an imprintless play among plays which do have an imprint. Even this reasonable procedure, however, has its risks, for many imprints are not what they seem.

The splendid University of Pennsylvania series of microfilms is of great assistance to those with no ready access to collections of old Spanish plays2. One of the first items to catch my eye in this series was Lope de Vega, Veinte y tres parte de sus comedias, y la meior parte que hasta oy se ha escrito, En Valencia, por Miguel Sorolla, junto a la Vniversidad, 1629. Miss Penney notes that Miguel Sorolla the Younger was indeed printing in Valencia beside the university during this period, and lists one book in particular, Castillo Solórzano's Huerta de Valencia, which was printed in the same year3. I had hoped that this Parte 23 would illustrate Sorolla's types and his manner of using them to print plays, but a glance showed that the volume was not to be trusted: the two preliminary leaves are typographically distinct from the body of the book, while the body of the book has neither continuous foliation nor continuous signatures.

This Parte 23, like many other collected volumes of the period, is made up. The contents, with foliation and signatures, are as follows:

|

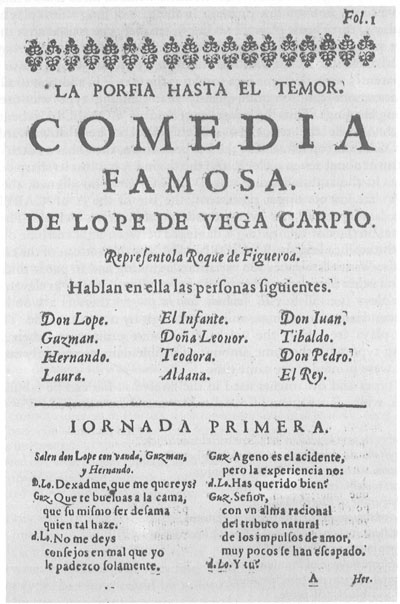

All these plays, then, are true sueltas, apparently intended for separate issue. Apart from the foliation and signatures, however, there is no sign that they were printed separately, for the type and the layout is the same in every case. One example, La porfía hasta el temor, will serve for all of them:

|

line 1, foliation: (Fol. l) texte italique (great primer italic) of Frangois Guyot, first recorded 15474. line 2, ornaments: a double row of 36 metal ornaments (origin not traced), line 3, title (LA PORFÍA HASTA EL TEMOR.): the text romeine (great primer roman) of Ameet Tavernier, first recorded 15535. line 4, heading (COMEDIA): the dubbelde text kapitalen (two-line great primer capitals, :10.4mm) owned, but probably not cut, by Christoffel van Dijck6. line 5, heading (FAMOSA): the capitales sur deux lignes de cicéro (two-line pica capitals, :7 mm) of Robert Granjon, first recorded in 15677. line 6, author (DE LOPE DE VEGA CARPIO.): the capitals of the ascendonica romaine (double pica roman) of Granjon, cut in 15698. line 7, performer: as line 1, texte italique of Guyot. line 8, cast list heading (Hablan en ella las personas siguientes.): as line 3, texte romeine of Tavernier. lines 9-12, cast list: as lines 1 and 7, texte italique of Guyot. line 13: rule (105 mm long), line 14, act-heading (IORNADA PRIMERA.): as lines 3 and 8, text romeine of Tavernier. text: a pica of about 84mm/20 lines. The italic is the médiane italique of Guyot, first recorded in 15539, while the roman is a version of the cicéro romain of Pierre Haultin, in use by 155810. The roman is not pure in any event, for apart from its own query, it contains the italic query of the Guyot médiane italique (see Figure 1, col. 1, line 3 of the text), and also the very unusual and distinctive query from the médiane romaine of Guyot (see Figure 1, col. 2, lines 3 and 9 of the text); first recorded in 154411. |

Figure 1

This pattern is the same in all twelve plays, except that the cast list occupies anything from three to seven lines, while in three cases a long title spills over into an extra line or lines. In the case of long titles (play 2, two lines; play 5, three lines; play 7, two lines), smaller type is used after the first line. In plays 2 and 5, the second line is apparently set in the Augustine (english) of Haultin, while the third line in play 5 and the second line in play 7 are apparently set in the same pica roman as the text12. In addition to all these similarities, one can see quite plainly that standing type was used for recurring headings. Thus the lower leg of the E of «COMEDIA» is bent up at the right, while the top right serif of the I is bent downwards. In «FAMOSA», the top left serif of the F is bent down, the O has a notch on the inner rim at about seven o'clock, and the second A has lost its sharp point at the top. In the author's name, the O of «LOPE» is misaligned, the G of «VEGA» has lost its upper right serif, the bar of the A of «CARPIO» is damaged, and the O has been bruised at about five o'clock. The e of «personas» in the cast list heading is damaged between eight and nine o'clock, and in the act-heading the R of «IORNADA» has the bottom of the tail bent upwards. With allowances for variations in inking and in paper thickness, these and other flaws are visible in all twelve plays. Finally, in eleven of the twelve plays (i. e. all but El honrado con su sangre) there is a wood-block tail-piece, triangular in shape and 26 mm high by 27.5 mm wide. Thus all twelve plays are clearly the work of the same printer; and their use of standing type with the same amount of visible damage strongly suggests that all were printed at the same time.

The types and ornaments used in the twelve sueltas can be tabulated as follows, where R = roman, IT = italic, M = metal ornament and W = woodblock:

|

Of these eleven, the preliminaries use R2 and R4. Instead of R1, they use a copy of the gros canon romain (2-line double pica roman) of Hendrik van den Keere13. Instead of IT1, they use the gros texte italique, series 1, of Robert Granjon (for Y LA MEIOR PARTE, etc.)14. They also use a smaller italic which I cannot identify but which is certainly adulterated, for it has two kinds of E (used in SE HA ESCRITO). Finally, they have two woodblocks: one, on the title-page, apparently represents Aquarius the water-carrier, and is 56.5 by 63 mm; the other is an ornamental L, in the dedication, about 26 mm square.

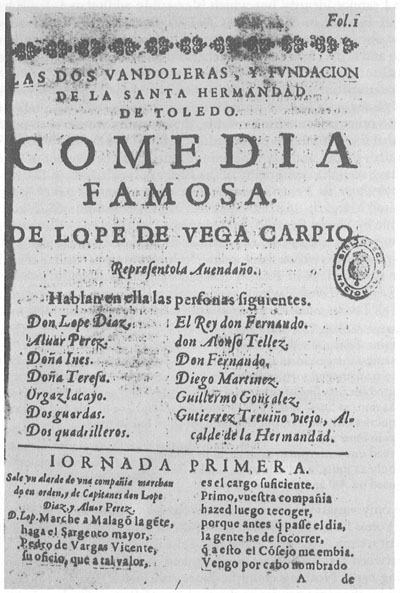

An examination of three books printed by Miguel Sorolla between 1627 and 1636 suggests that he printed neither the plays nor the preliminaries. Were no other information available, the next step would be to pursue the claim that the volume was produced «A costa de Luys de Soto Velasco vezino de Seuilla», that is, at the cost of Luis de Soto Velasco, resident of Seville. In fact I have seen the typography of the Parte 23 plays before, in Doze comedias nuevas de Lope de Vega Carpio, y otros autores, segunda parte, «Barcelona, Gerónimo Margarit, 1630». Despite this imprint, the volume was assembled in Seville by Simón Faxardo, probably in 1630, from material produced by his own presses and by those of Manuel de Sande (or Sandi), also of Seville, in the preceding two or three years15. One item in particular is strikingly similar to the plays in Parte 23: Las dos vandoleras, y fundación de la Santa Hermandad de Toledo, which is the second play in Doze comedias (see Figure 2). Las dos vandoleras contains the following typographical material:

|

The only variations between the typography of this suelta and that of the Parte 23 ones lie in the different use of metal ornaments, and in the slightly different setting of the title. Everything else is identical, down to the 105 mm rule between cast list and act-heading, and including the visible damage to standing type. Nothing could be more conclusive: Las dos vandoleras was printed by the same printer as the contents of Parte 23, and probably at the

Figure 2

same time. In 1981 I suggested, without going into details, that Las dos vandoleras was printed by Simón Faxardo shortly before 1630. I present these details now.

The British Library preserves, under the pressmark 593.h.17, a collected volume of Seville newsletters of the 1620s and 1630s. Over two dozen, covering the years 1624-32, are by Faxardo. One of them in particular, the Exhortación hecha al christianíssimo Rey de Francia of 1626 (593.h.17/43), contains all the roman and italic types in the table above. I also examined some books from the same period, notably Juan Bautista Porcel de Medina's Ramillete virginal of 1624 (Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, 3/56598), Juan Salvador Baptista Arellano's Antigüedades y excelencias de la villa de Carmona of 1628 (British Library, 574.e.21), and Pedro Ortiz's Noviciado, doctrina y enseñanza de la santa provincia de Los Angeles of 1633 (Trinity College, Dublin, BB.o.23). These confirm the evidence of newsletters. In particular, Arellano's Antigüedades contains samples of everything, including M1 and W1 (on ¶7v), with the exception of R7. There is no doubt that Las dos vandoleras and the twelve sueltas from Parte 23 were printed in Seville by Simón Faxardo, probably around 1626-28.

The guess-date depends on Faxardo's use of the roman text-types R6 and R7; such types usually have a relatively short life. It is not absolutely certain, but the volume probably was issued in 1629. The dedication of the «publisher», Luys de Soto Velasco, is dated 20 July 1629. He claims that enforced leisure due to lack of business and the fact that no fleet was sailing led him to read some Lope de Vega. He adds that he took advantage of this leisure to have some plays printed, since he believed them to be Lope's best work. Soto is not known to have taken part in any other publishing ventures.

Reading between the lines, we can see an entrepreneur whose business was suffering from the damage done to Indies trade by Piet Hein's capture of the Spanish treasure fleet in 1628; he therefore turned to publishing to earn a dubious penny by issuing a doubtfully legal collection of «Lope's» plays. He may have bought a stock of sueltas from Faxardo and got another printer to produce the set of preliminaries. (I have not investigated the printing of the preliminaries, but they were produced in Seville).

Whatever the exact circumstances of Soto's publication of Parte 23, the date and place have some implications for literary historiography. The seventh and tenth plays (La industria contra el poder, y el honor contra la fuerza and La cruz en la sepultura) are really Calderón's plays Amor, honor y poder and La devoción de la cruz. The sueltas contained in Parte 23 of c. 1627 represent the earliest printing of any Calderón plays, antedating considerably El astrólogo fingido, which appeared in Diferentes 24 (Saragossa, 1632). Amor, honor y poder, with a performance fee paid on 29 June 1623, has always been regarded as an early play, but the date of La devoción de la cruz has been disputed16. Here is more evidence that Calderón was writing some of his best known plays earlier than has been supposed17. In addition, Parte 23 helps to account for Calderón's later complaints about bad editions and incorrect attributions of his plays. We can easily suppose that a young writer would be annoyed if his first published drama appeared under the name of someone else, even if that someone else were Lope de Vega.

As for the other ten plays in the volume, only three of them are indisputably Lope's, according to Morley and Bruerton18. I deal with them briefly:

|

1. El palacio confuso (Morley and Bruerton, pp. 524-25). Of doubtful authenticity; several metrical features indicate that Lope was not the author. Published in Diferentes 28 (Huesca, 1634) and in Escogidas 28 (Madrid, 1667), where it is attributed to Mira de Amescua, whom some critics see as a more likely author. The present suelta appears to be the first edition. 2. El ingrato (Morley and Bruerton, pp. 483-84). Of doubtful authenticity in its present form. Attributed in some sueltas (e. g. British Library, 11728.h.4/8) to Calderón but not his. Different from El ingrato arrepentido, which appeared in Lope's Parte 15 (1621). The present suelta appears to be the first edition. 3.

La tragedia por los

celos. By Guillén de Castro. According to Paz y

Melia, MS 17.330 of the Biblioteca Nacional, which is of

this play, ends with the words 4. El labrador venturoso (Morley and Bruerton, pp. 347-48). An authentic undated play; they suggest 1620-22. Printed in Diferentes 28 (Huesca, 1634) and in Lope's Parte 22 (Madrid, 1635). The present suelta appears to be the first edition. 5. La creación del mundo y primera culpa del hombre (Morley and Bruerton, pp. 440-41). Of doubtful authenticity. Not the same play as Luis Vélez de Guevara's La creación del mundo. Many sueltas survive, some attributed to Lope, some to «un ingenio de esta corte»20. The present suelta appears to be the first edition. 6. La despreciada querida. By Juan Bautista de Villegas. Paz y Melia (1,151, no. 1002) lists two manuscripts. One, although of Act III only, is autograph and signed by Villegas in Valencia, 15 May 1621. The present suelta appears to be the first edition. 8. La porfía hasta el temor (Morley and Bruerton, pp. 533-34). Of doubtful authenticity. Printed in Diferentes 28 (Huesca, 1634), in which reference is made, as here, to a performance by Roque de Figueroa. Morley and Bruerton suggest that if the play is by Lope, it dates from 1595-1604, long before Figueroa was on the stage. Paz y Melia (1, 67-68, no. 466, item 2) records a seventeenth-century manuscript, attributed to Lope. The present suelta appears to be the first edition. 9. El juez de su causa (Morley and Bruerton, pp. 345-46). With the title ...en su causa, an authentic undated play; they suggest about 1610. Printed in Lope's Parte 25 (Saragossa, 1647), that is, about twenty years later than our suelta, which appears to be the first edition. 11. El honrado con su sangre. Not in Morley and Bruerton. In his Catálogo bibliográfico y biográfico del teatro antiguo español (Madrid, 1860), p. 94a, La Barrera suggests Andrés de Claramonte as the author. He had never seen the play, since he quotes only the lost Parte 24 (Madrid, 1640). In his recent study of Claramonte, Alfredo Rodríguez López-Vázquez accepts the attribution, suggesting that the play is consistent with developments in Claramonte's metrical habits. He also draws attention to what is apparently the only other surviving print, in the Hispanic Society of America collection: Andrés de Claramonte y «El burlador de Sevilla» (Kassel, 1987), pp. 187, 146, n. 54. 12. El hijo sin padre (Morley and Bruerton, p. 338). An authentic undated play: they suggest about 1613-18. The present suelta appears to be the first edition. |

It is worth noting that the lost Parte 24 contained the same plays as our Parte 23. The last bibliographer to see a copy was apparently Nicolás Antonio, in the seventeenth century. Several more modern bibliographers quote him, among them La Barrera (Catálogo, pp. 448b-49a). Presumably our Parte 23 was either reissued or reprinted in Madrid in 1640.

Another parte which clearly has some relationship with ours is Diferentes 28, that is, Parte veinte y ocho de comedias de varios autores (Huesca, Pedro Blusón, 1634). It contains:

|

As can be seen, no fewer than seven of the twelve plays were earlier printed in our Parte 23. However, Parte 28 has continuous pagination and signatures, although the plays it contains are desglosables21.

This discovery that a volume of plays ostensibly produced in Valencia in 1629 was really printed in Seville reminded me of another such volume: Doze comedias nuevas del Maestro Tirso de Molina, «Valencia, Pedro Patricio Mey, 1631». This is the second «edition» of Tirso's famous or infamous Primera parte, and it is well known that the new «edition» is really a new issue of the original impression, with new preliminaries22. The first issue ostensibly appeared in Seville, printed by Francisco de Lyra in 1627 for Manuel de Sande. In an illuminating study of the problems posed by the Primera parte, Don Jaime Moll refused to believe that the «Valencia» preliminaries were genuine, although he did not pursue the matter further23.

The types and ornaments used in the preliminaries of the «Valencia» edition of Tirso's Primera parte are as follows:

|

These are the only four faces common to the «Valencia» preliminaries and the type-stock of Faxardo as it was in 1626-28. The preliminaries also have the following material, not found in Faxardo's stock:

|

There is no evidence here that Simón Faxardo had anything to do with the preliminaries of the «Valencia» issue. However, if we look at the Novus index librorum prohibitorum et expurgatorum printed by Francisco de Lyra in 1632 (British Library, 617.l.27), we find R1, R2, R3, R5, a set of capitals which corresponds to R8, R9, IT3 and IT4. IT4 is measurable as 96mm/20 lines, and the only thing lacking is W2, which is not to be wondered at in the case of a coat-of-arms. The simple conclusion is that it was Lyra himself who reissued in 1631 the book he had earlier issued in 1627, using Mey's name to conceal his involvement.

There was evidently quite a difference between the type Lyra had in 1627 and the type he had in 1631. Or could it be that the 1627 edition was not printed by Lyra? Alan Paterson satisfied himself and other bibliographers when he argued in 1967 that Lyra had printed the volume, but in the light of this fresh discovery, I may be forgiven for reopening the question28.

The type and ornaments used in the first issue of the Primera parte are as follows (excluding the fourth play, La villana de Vallecas, for reasons which will become clear):

|

The above list is based on photocopies (kindly supplied by Professor X. A. Fernández) of the Vienna Nationalbibliothek copy of the 1627 issue and the Madrid Biblioteca Nacional copy of the 1631 issue (R/18.710). The Madrid copy's texts of La villana de Vallecas and Mari-Hernández la gallega have been replaced by modern sueltas, but the texts otherwise correspond.

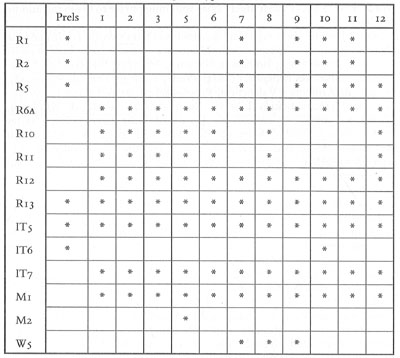

This list, however, conceals two facts: not all the types are used in every play; and not all the types are used in the same way in every play. With regard to recurrence, the table opposite illustrates the point clearly. Some types (R13 and IT5) are used in all the plays and in the preliminaries. Others (R6A, R12, IT7, M1) are used in all the plays. However, types such as R1, R2, R5, R10, and R11 suggest that the volume consists of two sections: 1, the preliminaries and plays 7, 9, 10, and 11; and 2, plays 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 12. This is supported by the recurrence of identifiable damaged sorts used for headings. In section 1 the I of «COMEDIA» (R1) has damage to the bottom left and top right serifs in the four plays (the I of «COMEDIAS» on the title-page of the preliminaries may be the same, although it is hard to be certain); and the D of «DE MOLINA» (R13) has lost its upper serif in all four plays. In section 2, damage to the top leg of the E of «COMEDIA» (R10) and the top of the L of «FAMOSA DEL» (R11) can be seen in plays 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 12. There is every reason to suppose that standing type was used in all of these cases.

Tirso's Primera parte, types and ornaments

Play 8 is slightly anomalous. The presence of types as shown in the table suggests that it belongs to section 2. Moreover, the damaged L referred to in the previous paragraph is used in the words «PARTE DEL». However, play 8 seems really to belong to section 1. First, the wood-block W5 is used as a tail-piece in plays 7, 8, and 9 (plays 10 and 11 end at the foot of a page, with no room for an ornament). Second, the way in which types are used links play 8 with section 1. Thus section 2 plays use italic capitals to record performance (that is, with the word «REPRESENTÓLA» or «REPRESENTARONLA»: see plays 1, 2, 3, 5, 6; not present in 12). Section 1 plays use capitals and lower case («Repreƒentòla»: plays 7, 8, 9, 10, 11). All the plays in section 2 use the simple heading «PERSONAS» for the list of characters. Those in section 1, including play 8, have an unusually long formula («Las perƒonas que hablan, ƒon las ƒiguientes».). The ornaments used at the head of the first page of each play are in three rows in section 2 and in only two rows in section 1. (The number of ornaments used is always 59 in section 2; in section 1, 44 are used in 7, 9, 10, and 11, but only 40 in play 8). Finally, it may be noted that at the end of section 1 (that is, at the end of play 11) are the words «LAUS DEO», a strangely final-sounding phrase to use in the middle of a book.

In searching for these types and ornaments in Lyra's work, I examined the Declaración de los prodigiosos señales del monstruoso pescado que se halló en un río... en Alemania (1624; Biblioteca Nacional, MS 2355, fols 516-17); M. de Cervantes, Novelas exemplares (1624; Trinity College, Dublin, R.mm.58); Damián de Armenta y Valençuela, Relación del auto general de la fe [2 December 1625] (1625; British Library, 593.h.17/20); Alonso de Sandoval, Naturaleza, policía... costumbres i ritos... de todos etíopes (1627; Chester Beatty Library, Dublin); Martín de Roa, Monasterio antiguo de San Christóval en Córdova (1629; British Library, 4625.b.18); the Novus index of 1632 referred to earlier; and some twenty other small items from 593.h.17 and other sources.

Together, these items contain all the type and metal ornaments used in the Primera parte. The Sandoval book of 1627 contains wood-block W5 on E4r, as Paterson noted («Two bibliographical studies», p. 62). I also found this block in the Relación verdadera que la Cesárea Magestad del Emperador de Alemania a embiado al Rey..., dando cuenta de la feliz Vitoria que en 12. Otubre... tuvo el Duque de Frislant... (Lyra, 1633; British Library, 593.h.17/119). I did not see W4, the historiated P, but Paterson saw it in Lucena's Historia de la vida del P. Francisco Xavier, printed by Lyra in 1619 («Two bibliographical studies», p. 61). Neither of us noticed W3, the May-block, in other books. It is true that something odd happened in Alonso de Sandoval's book, with Part 4 being printed separately, with different foliation, signatures and type, but this cannot overturn all the other evidence, which indicates overwhelmingly that Lyra printed the preliminaries and eleven of the twelve plays in the Primera parte.

My explanation for the existence of two sections is straightforward enough: Lyra did not print all of the volume at the same time. As Moll has pointed out, on 11 June 1624 Tirso obtained a privilege to print Part I of his plays; the privilege implies that the necessary approval had been obtained37. Furthermore, Tirso stated in 1624, in the prologue to his Cigarrales de Toledo (Madrid, 1624), that twelve plays, comprising the first of many partes that he hoped to publish, had already gone to press38. One possible explanation of these facts and of the typographical evidence from the Primera parte is that Lyra actually began to print the twelve plays in the latter part of 1624. The volume as it now exists contains sixty-two-and-a-half sheets of text. If there were any urgency, a sheet could easily be set and printed in a working day, giving a production time for such a volume of a little over ten weeks; but Lyra was a busy printer, with more urgent calls on his presses than a collection of plays: it would not be surprising if production dragged on into 1625. On 6 March 1625 -a date engraved on the heart of every tirsista- the Junta de Reformación singled out Tirso for his writing of pernicious plays, and ordered him to stop. It also recommended that no further permission be granted for the publication of any plays or novels. There was nothing in this to withdraw the privilege already conceded to Tirso, but as Moll has indicated («El problema», p. 93), the order to stop writing plays probably implied official action against any attempt to publish, those already written. One can well imagine that Tirso's printer, Francisco de Lyra, and his publisher, Manuel de Sande, were dismayed to receive news of the decisions of 6 March. (They possibly heard the news from Tirso himself, who was in Seville from April 1625 to April 1626.) They may not have wept much for Tirso, but since both of them had regularly been involved in printing and publishing plays and novels, they almost certainly shed metaphorical tears for themselves.

If the printing of the Primera parte had not been completed by the time the Junta's decisions reached Seville, one would have expected an interruption. There is no sign in the text that this happened: damaged standing type seen in the first play is still present in the last. It is perhaps more likely that printing had finished, and that distribution was about to start or even had started. If it had, it presumably proceeded no further for two years. At the end of this time, since nothing drastic had happened to Tirso, and since his ten-year privilege had not expired, Lyra and Sande decided to go ahead with publication. If preliminaries had been printed for issue in 1625, they presumably scrapped them and printed a new, somewhat curtailed set, which nevertheless alluded to the volume's right to be published by printing «Con Privilegio» on the title-page, and which gave an honest imprint and date.

The contents of the volume printed in 1624-25 are another matter entirely. If my hypothesis is correct, half the plays were scrapped and another six (4, La villana de Vallecas; 7, El castigo del penséque I; 8, El castigo del penséque II; 9, La gallega Mari-Hernández; 10, Tanto es lo de más como lo de menos; and 11, La celosa de sí misma) were printed and inserted in their place. The fact that the volume is a desglosable -«disbindable»- with either three or four signatures allotted to each play, made this possible. (For example, the first three plays collate A-C8 D2, E-G8 H4, I-L8, although plays 7-11 have only three signatures each). Of course preserving the supposedly continuous foliation was still a problem, but Spanish compositors of this period do not seem to have worried much about such matters: only fifty of this volume's 296 pages are correctly numbered.

As for play 4, La villana de Vallecas, it shows no signs of being printed by Lyra. Its types are as follows:

|

There can be little doubt that this play was printed by Andrés Grande of Seville in the late 1620s. The British Library collection of pamphlets referred to earlier (593.h.17) contains numerous items printed by him during this period. They show all the types of La villana de Vallecas, including the mixture of R16 and R17, as well as M2, the seven-pointed stars. From the state of the type, it would seem that the most likely date for his printing of the play is 1626-27. This supports my view that the replacements for plays 7-11 were printed in 1627, at the same time as the preliminaries.

In other words, I believe that while the volume issued by Lyra and Sande in 1627 is at least in part the volume that Tirso said was at press in 1624, six plays are different. For whatever reason (but conceivably because the plays in question were known to have contributed towards official disapproval of Tirso's writing), six of the original plays were suppressed, and six others put in their place. At the same time, the preliminaries were printed or reprinted; if reprinted, in order to change the contents-list and to refresh the date. We can only guess at the titles of the plays which were removed. Whatever they were, their presence did not make the volume correspond to the famous list discovered by Paterson40. Equally mysterious are the reasons which caused one of the replacements to be printed by Grande.

On 13 June 1627 a decree was issued which attempted to control printing in Spain by insisting on correct dates and imprints and on the observation of the appropriate legal requirements. If I am right, the 1627 issue did not correspond exactly to the volume licensed in 1624, and it certainly did not publish all the right documents. Perhaps for this reason, or possibly because the authorities did react unfavourably to the publication of Tirso's plays, Lyra and Sande stopped promoting the book, allowed some time for official vigilance to relax, then issued the book again, with a new and completely false set of preliminaries printed by Lyra in 163141.

All of this is hypothesis, of course. I differ slightly from the hypothesis previously proposed by Professor Moll, but I agree with his main contention, that there was no earlier edition of the Primera parte. What we now have is as close as we are likely to get to the volume of plays which was at press in 1624, and for which Tirso was granted a privilege that same year. Given that Lyra and Sande were effectively Tirso's printer and publisher from 1624 to 1631, it is at least interesting that Sande (who was a printer as well as a publisher) should have printed El burlador de Sevilla around 1627-2942. I am reluctant to be drawn into the current argument about who wrote this play, but the fact that it was printed in Seville by Sande (and not in Barcelona by Margarit) is in keeping with Tirso's authorship; it is also in keeping with that of Claramonte, who, although he came from Murcia, had strong connections with Seville.

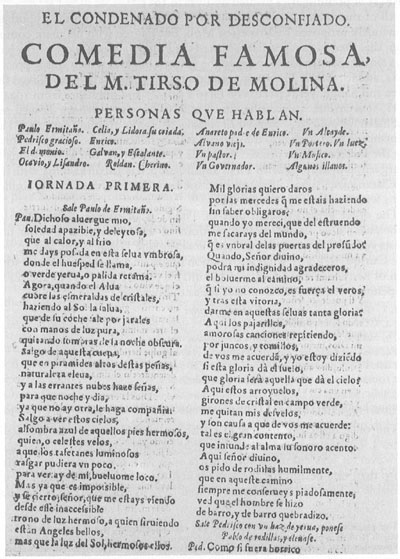

The other great problem play of Tirso's is of course El condenado por desconfiado. One of the earliest editions of El condenado is a suelta now preserved in Copenhagen (Collectio dramaticorum hispanicorum, vol. 11; 75iv, 53). Curious to know what information might be gained from an investigation of its typography, I obtained a suitable photocopy43. The types of the Copenhagen suelta of El condenado are as follows (see Figure 3):

|

The only difficulty here is IT4, the copy of Granjon's english italic, series 3. I have not seen Faxardo use it: he had the original Granjon series 1. However, it was common for printers such as Faxardo and Lyra to have more than one design for the same body, and, as we have seen, IT4 was available to Lyra in 1632. I have not seen Lyra use either R4 or R7, so I am

Figure 3

inclined to opt for Faxardo. R7 is a very rare face anywhere, and my only records for its use in Spain are both of Seville: Hernando Díaz in 1575 and Andrea Pescioni in 1582. As for the date of this suelta, Faxardo's recorded use of R7 is restricted to two items, both of 1626: c. 1626 seems the best guess available at present44.

This guess-date would make the Copenhagen suelta of El condenado the first surviving edition of the play, antedating by nearly ten years the version printed in Tirso's Segunda parte (Madrid, 1635). The guess-date also appears to contradict the conclusion reached by Dan Rogers in his edition (p. 38, see my note 43), a conclusion based on the fact that the parte text is more complete than the suelta, and so could hardly have been printed from it. The apparent contradiction could be explained if parte and suelta derived from a common ancestor, conceivably a fair copy of the original, or an earlier suelta, now lost. The parte text would have followed the common ancestor closely, reproducing even obscure passages, while the editor or compositor of the suelta would simply have cut these obscurities, as Rogers suggests.

The doubts about Tirso's authorship of El condenado stem from his remark, in the dedication of his Segunda parte, that of the twelve plays in the volume, only four were his. The attribution to Tirso in the suelta does not possess this ambiguity, but it does not clear away the difficulty: Tirso's remark could be taken to refer to the existence of an edition like the suelta, in which the play was wrongly attributed to him.

After this lengthy excursus, we can perhaps return to the starting-point of this study, the suelta of Tan largo me lo fiais. All the typefaces used in Tan largo have already been mentioned above, but of course it is the combination of faces and their condition which point to a particular date and printer. The faces are as follows (see Figure 4):

|

Figure 4

|

After a long search for this distinctive combination of text-types (R6C and IT7B), I found them only in Ludovico de Copiaria Carmerineo (translator), Atroces hechos de impíos tyranos, por intervención de franceses... Colegidas de autores diversos... y escritas en lengua latina («Valeria, 1635»; British Library, 1445. f. 20/15). This item has R2 and R9 as well, but at first sight it is useless as evidence because of the false imprint and the lack of a printer's name. However, it has a wood-block, a large putto with unusually well-defined lips, measuring 77.5 mm by 55.5 mm. The block was Lyra's, used by him in two similar pamphlets, Vitoria que tres caravelas portuguesas tuvieron contra los olandeses and Vitoria que el governador de Bolduque tuvo contra el príncipe de Orange (both of 1629: British Library, 593.h.17/90, and 593.h.17/91). As we have seen, Lyra had R10 and IT5, the copy of Granjon's parangon cursive. In fact, he also had the original Granjon at the same time, although they seem to have been kept separate, at least until 1632. It therefore appears that Tan largo me lo fiais was printed by Francisco de Lyra in Seville in or about 1635. To confirm this, one would need to see several books printed in pica over the five years 1633-37. I have seen only pamphlets and newsletters for these years, and my final identification depends on a wood-block, which could have been lent. It should be emphasized that there is no question of Lyra's not having Haultin's pica roman and italic during the 1630s: he had both of them. What I have not been able to do is examine a book with his imprint which shows these two faces in exactly the same state as in Tan largo. Even if it turns out that Lyra did not print the play, I believe that it will be found to have been printed in Seville in the 1630s45.

This study was not initiated with the intention of drawing any conclusions about the authorship of El burlador de Sevilla or Tan largo me lo fiais. I have suggested, however, that it is at least interesting that El burlador was printed by Manuel de Sande during a period when Sande was acting as Tirso's publisher (even if the relations between an author and his «publisher», three hundred and sixty years ago, were less close than they might be today)46. As for the relationship between the two texts, my friend Dr W. F. Hunter has suggested to me that it can be most simply explained by the hypothesis that Tan largo is a reworking of El burlador, deriving from a printed copy. This is not the only possible interpretation of the evidence, but my claims that El burlador was published in Seville in 1630 and that Tan largo was printed there some five years later would seem to be quite consistent with that hypothesis.