The first edition of «El burlador de Sevilla»

Don William Cruickshank

University College, Dublin

Although a number

of years have passed since Don Jaime Moll drew attention to the

ten-year ban (1625-1634) on the printing of novels and plays in

Castile, scholars have been slow to take note of what his discovery

implies1.

The first implication must be that any novels or plays produced

with a Castilian imprint during these years should be regarded with

suspicion. Into this category falls, for example, the Primera parte of Tirso de

Molina's plays, apparently printed in 1627 by Francisco de Lyra of

Seville for Manuel de Sandi, «mercader de

libros»: Dr. Alan

Paterson pointed out some of the suspicious circumstances of this

book's production, although he has found evidence that it really

was printed by Lyra in 16272.

A second, related implication is that volumes of novels and plays

ostensibly printed in the kingdom of Aragon during this period may

not be what they seem: justifying the publication of his

Dorotea

(1632), Lope de Vega wrote that «también ha

obligado a Lope dar a la luz pública esta fábula el

ver la libertad con que los libreros de Seuilla, Cádiz y

otros lugares del Andaluzía, con la capa de que se imprimen

en Zaragoza y Barcelona, y poniendo los nombres de aquellos

impresores, sacan diuersos tomos en el suyo, poniendo en ellos

comedias de hombres ignorantes que él jamás vio ni

imaginó

»3.

As I shall try to show, the curious remark that the booksellers

«sacan diuersos tomos en

el suyo

» may be prompted by certain books

in particular.

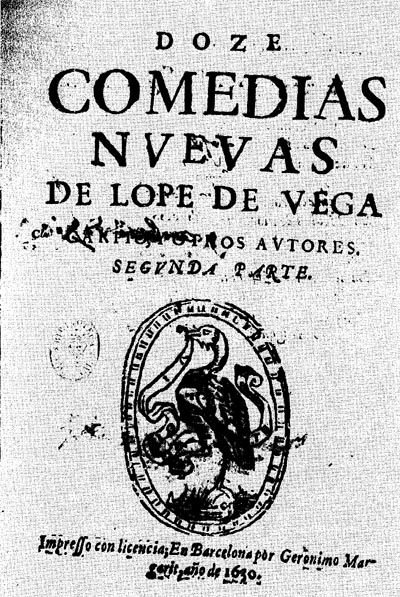

Tirso scholars have long been aware that there is something odd about Doze comedias nuevas de Lope de Vega Carpio, y otros autores. Segunda parte, Barcelona, Gerónimo Margarit, 1630 (see fig. 1, title-page). The Biblioteca Nacional copy (R-23136), which is apparently unique, has no continuous foliation; while the book is imperfect and in poor condition, it is obviously printed in a heterogeneous collection of type; and the signature-letters at the foot of the pages reinforce and even add to the confusion created by the uncertain foliation. El burlador de Sevilla is the seventh play, but it is foliated from 61 to 82. It has been noticed that the eleventh play, Deste agua no beberé, is foliated from 41 to 60, and that the two therefore fit4; moreover, Deste agua is typographically very like El burlador. The eighth play, Marina la porquera, foliated 1 to 20, also bears some typographical resemblance to El burlador, though this is less striking.

When we try to relate the signatures of these three plays to their folio numbers, we at once encounter a difficulty. El burlador de Sevilla has three gatherings signed K, L, M; its collation is K-L8 M6, a quarto in eights. The signature alphabet has no J, but there are still nine letters before K, and nine times eight is seventy-two. How can the first leaf of signature K be numbered 61? The answer is not as elusive as might be thought, and is provided by a further examination of the plays' signatures. Deste agua no beberé (foliated, it may be remembered, 41-60) collates G-H8 I4. The first four leaves of gathering G are signed G, G2, G3, G4, and the others are unsigned: this was normal practice around 1630. Gathering H also has four signed and four unsigned leaves. Gathering I, which consists of only four leaves, has two signed and two unsigned. That is to say, gathering I never had eight leaves, otherwise all four of the «remaining» leaves would be signed; they would also be disjunct singletons, not (as they are) two conjugate pairs. To put it another way, the printer who set up Deste agua no beberé so designed it that it could with equal ease be bound in a volume, or by itself. This practice was so common in Spain, especially around 1630, that the language has a special word for it: desglosable «disbindable». El burlador de Sevilla is also desglosable; that is, it was planned as a separate (or rather, separable) unit, and its third gathering had six leaves from the outset. Marina la porquera is somewhat different in that collation and foliation do not give it away immediately: it could be the first play of a collected volume, but it could also be a true suelta, designed to be sold on its own. It will suffice at this stage to accept that it could be a desglosable and that it is typographically linked to the other two.

Fig. 1. Title-page, Doze comedias

There are therefore indications that our three plays came from, or were designed for, a volume (or volumes) in which every play took up three letters of the signature alphabet, although the number of leaves might vary, depending on the length of the play. (It may be noted à propos of this point that Marina actually ends on the foot of folio 19r; nineteen, an odd number, would create that binder's plague, the disjunct leaf, so some verse and a large ornament were used to fill up 19v and folio 20.) The makeup of this conjectural volume would therefore have been as follows:

- 1 Marina la porquera: A-B8 C4, 20 leaves, foliated 1-20.

- 2 Unknown: D-E8 F4, 20 leaves, foliated 21-40

- 3 Deste agua no beberé: G-H814, 20 leaves, foliated 41-60.

- 4 El burlador de Sevilla: K-L8 M6, 22 leaves, foliated 61-82.

- 5 Unknown: first gathering signed N, first folio 83

- 6-12 Unknown, although we know the signature letters of each play; but foliation can be estimated only approximately.

The answer to one question-how can nine gatherings take up sixty leaves-has raised many more questions: if this conjectural volume really existed, or was planned, who printed it, and when? If it was not Margarit, was he merely the person who assembled the volume we now have? Or (suspicion growing) did Margarit have anything at all to do with either volume? To answer these questions we must turn to type and ornaments and the style in which they are used. To emphasise the need for caution, it may be first pointed out that the woodblock on the title-page of Doze comedias was noted by Vindel in his book on Spanish printers' marks: he depicted it and attributed it to Gerónimo Margarit, Barcelona5. When we look more closely, we see that his authority for doing so is derived solely from the volume we are investigating. Evidence like this is worse than useless.

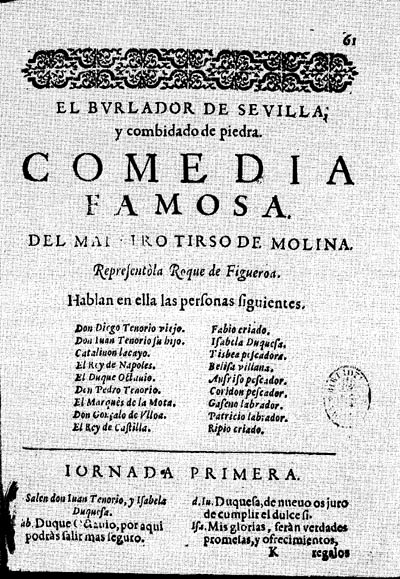

The types used in El burlador de Sevilla are as follows (see fig. 2):

|

Page-head ornaments: an arabesque fleuron probably cut by Robert Granjon, first used about 15606. For ease of reference it may be called M1 (where M stands for «metal ornament»). Lines 1 and 2: the text romeine (anglicè, great primer roman) of Ameet Tavernier of Antwerp, first used in 15537. As it is the third roman in terms of size, it may be called R3. Note damaged O of BVRLADOR. Line 3: the gros canon (two-line double pica) of François Guyot of Antwerp, first used in 1546, here adulterated8. The A is foreign, and the C is certainly not that shown in specimens of this face; however, the C's heavy serifs are not out of keeping with some of the other letters, and it may be an authentic early design, as is the case with the M. All letters slightly damaged. R1. Line 4: the capitales sur deux lignes de cicéro (two-line pica capitals) of Robert Granjon, dating from 15499. Minor damage to F, first A, M and S. R2. Line 5: as lines 1 and 2; minor damage to a number of letters. Line 6: the texte italique (great primer italic) of François Guyot, first used in 154710. IT1. Line 7: as lines 1, 2, and 5. Damage to cross-bar of H, bowl of p. Dramatis personae: the médiane italique grasse (pica italic) of Pierre Haultin of La Rochelle, first used about 155011. Some of the capitals, e. g., M and R, are cast too upright; this fault will be true of any type cast from the same badly justified matrices. Adulterated with some foreign type, of which only the v can be identified positively as being from Guyot's médiane italique (Klv, col. 1, line 15, v of vela).12 IT2. Act-heading (IORNADA PRIMERA): as lines 1, 2, 5, and 7. Note damaged O. Text italic: as dramatis personae. Text roman: the gros cicéro romain (pica roman) of Robert Granjon, first used about 156813. Used here on a body of 84 mm/20 lines. The original queries are adulterated with large italic ones; N, R and S are badly cast and tilting; acute accents predominate although there are many examples of à and ò; ê is very scarce (e. g., L6v, col. 2, line 7). R4. Running headlines: as line 6. |

When we turn to Deste agua no beberé we find the same types used for exactly the same purposes. Even more significantly, the damaged O of BVRLADOR reappears as the O of NO; the words COMEDIA FAMOSA are printed from the same slightly damaged types; the M of MOLINA recurs in CLARAMONTE; the H of Hablan and the p of personas are used again in the same position; and the same damaged O is used in IORNADA. There can be no doubt that the two plays were produced by the same printer, and that they were sufficiently contemporaneous for it to be worth the printer's while to leave recurring headings (COMEDIA FAMOSA, Hablan en ella las personas siguientes, IORNADA PRIMERA) in standing type. Finally, the use of the same design of type for the same purpose in every case is very strong evidence that the two items were planned as part of one book.

The case of Marina la porquera is again less clear-cut. There are no ornaments at the top of the page. The play's title is printed in Tavernier's text romeine (R3), as in the other plays, although no single identifiable types are present. The words COMEDIA FAMOSA are also set in the same design of type as in the other two plays, but again the identifiable damaged sorts are absent. The Guyot gros canon (R1) is adulterated in the same way, however. The name of the author is set in the capitals of R4, not in R3 as in the others; yet if we pause to think, we can see that the words DEL BACHILLER ANDRÉS MARTIN CARMONA could not possibly fit into the page if they were set in R3; they take up the entire width of the measure as it is. There is no reference to who performed the play («Representòla...»). This is less surprising if we remember that Carmona is known to literary history only for this play, and that the play is known only in this edition. Roque de Figueroa (who performed El burlador de Sevilla) and Antonio de Prado (Deste agua no beberé) were among the leading actors of their day. It does not seem likely that anyone so famous performed Marina la porquera. The rest of the play is set in the same designs of type as are the other two, except that the act-headings of the second and third acts are R4, not R3. I have not found any recognisable types, but the body of the text-type is the same, and the same miscast and foreign sorts are present.

Fig. 2. First page, El burlador de Sevilla

Summarising the evidence, we can say that the six typefaces used to print El burlador de Sevilla and Deste agua no beberé are also used in Marina. With minor exceptions, they are used for the same purposes. Where the body-size of the type can be measured, it is the same. Where adulteration is present, it is also the same. Only the row of ornaments (M1) is absent, and it is at least understandable that the first play might be different from the others in this respect. None of Marina's identifiable types appears to recur in the other two plays, but it should be remembered that damage occurs in the process of printing, as foreign matter in the ink or paper is squeezed into the soft type-metal by the platen of the hand-press. Damage visible in the third or fourth play in a volume might not have taken place until after the first play was printed. In fact, the evidence of six type-faces out of six, supported by body-size and adulteration, is virtually conclusive: the printer of all three plays was the same. All that is lacking is firm evidence that the three once formed part of the same volume. It may safely be said, however, that the typographical design of the three is more homogeneous than is the case with many volumes which were printed as a unit by one printer.

If it is accepted that two, perhaps three of the plays in Doze comedias once formed part of a now lost volume, the next question must involve the identity of that volume's printer. At first sight we have all of Spain to choose from, and we are not even restricted to 1630; but in fact, we are not without evidence to guide us in the initial stages of the search.

First of all, there is Lope's reference to the activities of Seville booksellers. As it stands, it seems much more appropriate to the made-up Doze comedias than to the volumes which were dismembered in order to assemble it, but we may let that pass for the moment. Then there are the plays: El burlador de Sevilla, set partly in Seville; Deste agua no beberé, set partly in Seville and written by Claramonte, who was particularly associated with Seville; and Marina la porquera, written by a man of whom we know nothing, except that Carmona is only twenty miles from Seville14. This is weak evidence, and circumstantial, but better is available from type. As I have argued elsewhere, a high proportion of Flemish type in a Spanish book is characteristic of Seville printing15; three Flemish designs out of six is a high proportion. More particularly, the use of Guyot gros canon (R1) is restricted, in my experience, to the Seville area16.

The next part of the investigation therefore involves examining the work of Seville printers for the six typefaces that have been identified, together with M1 (which, for practical purposes, can be treated as another typeface) and the large woodblock which is used at the end of Marina la porquera (fig. 3; we can call it W1). To be as brief as possible, I can say that I have found these in the work of Manuel de Sande. This is the same person as the Manuel de Sandi who «published» the Primera parte of Tirso; his name also appears as Manuel Sande. Although he seems to have acted as a printer only from about 1627-1632 and to have produced comparatively little under his own name, he did produce enough for the evidence to be reliable.

The most useful work is Martin de Roa's Ecija sus santos su antiguedad eclesiastica i seglar (sic, no punctuation) of 1629 (British Library, 486.g.22[4]). This is useful mainly because it is one of Roa's more obscure works, not worth pirating. It contains the following:

The presence of two other designs may be noted for future reference:

|

Guyot's médiane italique (IT3); this probably accounts for the Guyot v in IT2. Guyot's ascendonica romaine (double pica roman), R5.17 |

The Compendio de lo que escriven los religiosos de la compañia en cartas de 1627 de lo que passa en... Iapon (B. L., 593.h.l7[75]), a newsletter printed by Sande in 1627, confirms his ownership of the Granjon gros cicéro (R4) and of the Granjon capitales sur deux lignes de cicéro (R2). The body-size of the gros cicéro is ca. 85 mm/20 lines, but this can be explained by the lesser shrinkage of the coarser paper used for the newsletter18. More important, there are examples of the Granjon ornaments (M1). Sande describes himself as an «Impressor, y Mercader de Libros» (i. e., both printer and bookseller) and gives his address as «Calde-genova», the Calle de Génova, a street associated with the book trade since the late fifteenth century.

A second newsletter, Gerónimo Pancorvo's Relación escrita al doctor Ioan Santoyo (B. L., 593.h.l7[85]), dating from 1629, contains examples of R1, R2, R3, R4, IT1, IT2, M1, and also of R5. The body-size of R4 is again ca. 85 mm/20 lines. It may be noted, for future reference, that R2 is in relatively good condition in all these items, as it is in El burlador de Sevilla.

All the typographical material used to print our three plays was therefore in the possession of Manuel de Sande of Seville, ca. 1627-1629. Since «all» here means seven typesfaces (including M1) and a woodblock, and also involves constants in the case of such variables as body-size and adulteration, there can be little doubt that he was the printer. One would need to examine more of his output in order to provide an accurate guess-date, but since he printed comparatively little, and that over a mere half-dozen years, there is no guarantee that such refinement would be possible. In any case, we can probably regard the date 1630 as a genuine terminus ad quem, since any wise salesman who wanted to interest the public in what is really a job lot of plays would give the real date in order to make them seem as new as possible.

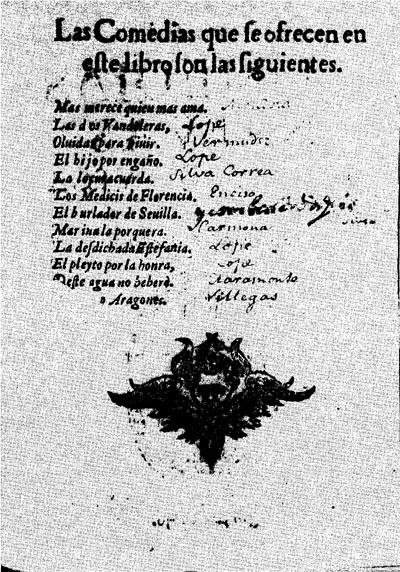

The demonstration that Manuel de Sande printed three of the plays in Doze comedias at once raises the question of who printed the rest of the volume. It seems best, in attempting to answer this question, not to regard the volume as a unit, but rather as thirteen separate units consisting of twelve single plays and a set of preliminaries. Since the printer of the preliminaries is the person most likely to have dismembered the original Sande volume and to have made up Doze comedias, we may begin with the preliminaries.

The word «preliminaries» is perhaps rather grand for what is actually a single leaf, of which the recto is a more or less standard title-page, while the verso contains the contents-list (fig. 4). Since there is no approbation, tassa (price-certificate) or preliminary document of any kind, it may be that there was once a second leaf, especially since the first leaf of the first play is lacking. The types of the preliminary leaf are as follows:

|

Recto, line 1: the capitals of the ascendonica romaine (double pica roman) of Granjon (R6)19. Line 2: the: 13 mm capitals of the Vatican specimen of 1628 (R7)20. The lower serif of the D is bent up, and there is a distinct notch just below the centre of the inside of the bowl. Line 3: NV VAS is apparently set in the parysse canon romein shown in the specimen of J. Enschedé, Haarlem, 1768, cutter unknown (R8)21. I have seen this face used in Seville in the 1670s. The S is upsidedown. The smaller E is so badly damaged as to be hard to measure, let alone identify; it is about: 10 mm (R9). Line 4: the capitales sur deux lignes de cicéro of Granjon (R2), here badly worn. Line 5: the text romeine of Tavernier (R3). Line 6: the texte italique of Guyot (IT1). Woodblock: as already indicated, this block is recorded by Vindel (see note 5). Lines 7

& 8: as line 6. Lines 3-14: IT1. Woodblock: the same block is used as a tailpiece in Los Medicis de Florencia, the sixth play. |

So far as I am aware, Gerónimo Margarit of Barcelona lacked R3 and IT1 in 1630 (the two Flemish designs); he did not possess at any time the above combination of faces. There is no evidence that he owned either woodblock, and indeed, the title-page woodblock is not found in any other book that I know of; the design of the block, on the other hand, is not unknown. Significantly, it originated in Seville, as Vindel shows, and was also used in Madrid22. There is no genuine record of its use in Aragon.

Once again Seville provides the answer. All the faces listed above and also the cherub woodblock formed part of the stock of Simón Faxardo, who worked in Seville from about 1612 to 1656. In 1628 Faxardo printed Juan Salvador Baptista Arellano's Antiguedades y excelencias de la villa de Carmona (B. L., 574.e.21); (Carmona, as we have seen, is near Seville). On §6r there appears the cherub block; on §7v the small triangular tailpiece which is used twice in Las dos vandoleras, the second play in Doze comedias. There are also examples of R7, R2, R6, R3, IT1. If we look at a slightly later Faxardo item, the Relación verdadera de la insigne, y milagrosa vitoria, que don Iorge de Mendoça... alcançó... contra el Cacis Cid Mahomet Laex of 1629 (B.L., 593.h.l7[92]), we find an example of a mixture of R8 and R9 as used on the Doze comedias title-page, R2 (in a suitably worn state), as well as R3 and IT1. A later work, Pedro Ortiz's Noviciado, doctrina y enseñanza de la santa provincia de los angeles of 1633 (Trinity College, Dublin, BB.o.23), shows that by then the battered R2 had been replaced. Other designs can be recognised, and the decorative initial P used in El pleito por la honra, the tenth play in Doze comedias, is used on E3r and P1v. This P is probably metal, not wood, and so not unique, but it seems to be the same piece of type.

Fig. 3. Tail-piece, Marina la porquera

There is not much doubt that Simón Faxardo was the printer of the preliminary leaf of Doze comedias. Such evidence as is available from worn and adulterated type suggests that the date 1630 is about right. As for the individual plays, we have seen evidence from ornaments that he also printed some of them. Los Medicis de Florencia is the most interesting of these: not only does it have the cherub woodblock as a tailpiece, but the same damaged R7 D is used in COMEDIA as has been noted on the title-page of Doze comedias. The text of the play is printed in an adulterated version of the cicéro romain (pica roman) of Haultin23. The most significant feature of the adulteration is the use of three queries: the correct roman one, a small italic one, and an ancient gothic design. The text italic is Guyot médiane italique (IT3); its shortage of capitals has been made good by the addition of roman sorts, some of them Haultin's. It may be added that both these text-types are the same as in Arellano's Antiguedades of 1628.

There is no space here for the provision of detailed evidence concerning these plays which have no direct connection with El burlador; however, on the basis of the adulterated text-types I have mentioned and of additional evidence which I have not, I attribute the following printings to Faxardo:

All the evidence points to the fact that these are true sueltas, printed to be sold singly, probably in the period 1625-1630, and bound together by Faxardo into Doze comedias in 1630. The last two make use of R2 with the foreign lower case R10, as on the verso of the Doze comedias title-page.

Three plays, Olvidar para vivir, El hijo por engaño, and Lusidoro (or Lucidoro) Aragonés, are not accounted for. Unlike the others, which are quartos in eights, Lusidoro is a quarto in fours (A-F4 G2) and is unfoliated. For this reason and because of its different typefaces, I do not think it was printed by Sande or Faxardo; but I believe it is Seville work. As for Olvidar para vivir, it contains the following typefaces: R2, R3, R4 (with large italic queries among the roman ones), R5, IT2. As we have seen, Sande had all of these typefaces, and he is certainly the best candidate (or the chief suspect) for this play's printer. The same is true of El hijo por engaño, which has the same type with the exception of R2. The two plays appear to be true sueltas: Olvidar para vivir collates A-B8 C4, foliated 1-20; El hijo por engaño collates A-B8 C6, foliated 1-22.

To sum up: in 1630 Simón Faxardo of Seville collected prints of six sueltas produced by his own presses, two sueltas probably produced by Manuel de Sande, also of Seville, one suelta produced by an unidentified Seville printer, and bound them all together with three desglosables from a volume produced by Sande. He gave this hotch-potch the title of Doze comedias nuevas de Lope de Vega Carpio, y otros autores, and added the words Segunda parte. No Primera parte of this series is known, and the Biblioteca Nacional copy of the Segunda parte is apparently unique. This is not surprising, if we consider how many times Faxardo performed the process just described. He was presumably dealing with plays which had not sold well in their previous existence, but it is unlikely that he had as many as 200 or even 100 copies of ten separate items (nine sueltas and the Sande volume); on the contrary, numbers are likely to have been small, perhaps very small indeed. This is why the Primera parte, which was probably a similar production, has not survived, and why the Segunda parte is so rare. It may be that the authorities realised that the volumes were not, as they seemed (I speculate about the Primera parte), Aragonese printings, and suppressed them.

It is perhaps more interesting but certainly harder to speculate profitably about the nature of the original Sande volume. It cannot have been a long-lost, «genuine» Primera parte of Tirso, for it began with a play by Andrés Martín Carmona and went on with a play by Claramonte: it must have been a tomo de varios autores. However, Manuel de Sande published the dubious Tirso Primera parte of 1627. Might he have acquired a group of Tirso plays prior to 1627, when the Primera parte was being planned? Might he have acquired more than the usual dozen, and then published the extra ones, among them El burlador de Sevilla, in other volumes? There is no telling, but the Sande connection, plus the fact that Tirso was better-known in Seville than in Barcelona, makes the authenticity of the Burlador a little more likely24.

The main use of the discovery that Sande printed the first edition of Tirso's masterpiece is, in theory, textual, but it is not easy to turn this theory into practice. It has always been possible to identify the preferences of the Burlador compositor with regard to accidentals. Now that we know which firm was involved, it is theoretically possible to identify other texts set by the same compositor; if one of those texts is a second or subsequent edition, and we can identify the earlier edition used as copy by the compositor, we shall then be in a position to judge how the compositor altered his copy, and thus to guess at the kind of copy used for the Burlador. The Burlador text is manifestly corrupt: it may be possible to distinguish corruption in the copy from corruption introduced by the compositor, and so to form a better idea of the play's textual history. To this end, and also in the hope of reconstructing the lost volume, I have looked for other Sande plays.

Professor V. G. Williamsen recently drew attention to a unique (?) Lope parte: Parte veynte y cinco, Barcelona, Sebastián de Cormellas, 163125. He noted the irregular foliation and signatures, and suggested that the book might be a combination of two desglosable volumes. His conclusions were on the right lines, but a little modest. The volume is made-up, but there is no sign that Cormellas was involved. The two preliminary leaves seem to be Seville work, and it is certain that some, if not all, of the contents were printed in Seville. The volume opens with La historia de Mazagatos, foliated 1-24, signed A-C8; next comes Nadie fíe en lo que ve, porque se engañan los ojos, foliated 25-46, signed D-E8 F6. The two plays are desglosables; that they belong together is indicated by the damaged standing type used in the headings of both. Here is a brief description of the type and layout of La historia de Mazagatos:

Fig. 4. Title-page verso, Doze comedias

|

Page-head ornaments: M1. Title: R3. COMEDIA: R1. FAMOSA: R2. Author: R3. Performer: IT1. Dramatis personae heading: R4. Dramatis personae: IT2. Act-heading: R4. Text roman and italic: R4 and IT2. |

Part of the text is printed in the cicéro romain of Haultin, a design also used by Faxardo; but while Faxardo's version of this face is characterised by three different queries, we have here the regular roman query used with the large italic query associated with Sande, as are all the other types just mentioned.

The rest of the plays in Parte veynte y cinco seem to be true sueltas, with the exception of El príncipe don Carlos, foliated 92-113, signed A-B8 C4 D2; El mayor impossible, foliated 189-208, signed A4 B-C8; and Nardo Antonio vandolero, foliated 235- 254, signed A-B8 C4. These are the fifth, ninth, and eleventh plays, respectively.

At first sight, we have here a different kind of desglosable, one in which the foliation but not the signatures reveals its identity. Closer examination shows, nevertheless, that the same standing type was used for headings as in the first two plays. There are still minor mysteries: the reason for the change in style of signatures, the fact that El príncipe don Carlos starts on an even-numbered folio, the odd signing of El mayor impossible; but it seems clear that these five plays were once part of a volume printed by Manuel de Sande about 1627-1629. Professor Williamsen's fear that the number of leaves between El mayor impossible and Nardo Antonio was too many is groundless (there are 26). Los Medicis de Florencia (28 leaves in the Doze comedias suelta) shows that 26 was not exceptional.

The discovery of this second Sande volume is of almost no help. In the first place, it is a second volume: we have two initial plays, and two different lots of standing type; we cannot make this into one volume. Secondly, Professor Williamsen's investigations show that Parte veynte y cinco apparently provides the first edition of all twelve plays contained in it. One consolation is that the parte does seem to fit the wording of Lope's complaint of 1632: here we have a Seville bookseller using the name of a Barcelona printer, bringing out pieces of other volumes as his own, and attributing plays by other writers to Lope (of the twelve, one is attributed to Pérez de Montalbán, the rest to Lope; some are definitely not his, and only three can be assigned to him with certainty).

Before leaving this volume, let us record the dates of its two approbations: the religious one is dated 4 January 1631, and involved Andrés Omella and Dr. Francisco la Peña; the civil one is dated 10 February 1631, and involved Diego Morlanes and Don Fernando de Borja. In both cases Saragossa was the ostensible place of issue.

The University of Pennsylvania collection has another volume which is evidently related to Parte veynte y cinco: Las comedias del fenix de España Lope de Vega Carpio. Parte veinte y siete, Barcelona, Sebastián de Cormellas, 163326. Like Parte veynte y cinco, this volume has a copy of the Don Quixote «Post tenebras spero lucem» block on the title-page (but a different copy). In this case the religious approbation is dated 4 January 1633, the civil one 10 February 1633. The same four people were involved, and the place of issue was again Saragossa. It is obviously against the odds that these four persons should have conspired to issue identically-worded documents precisely two years after they supposedly issued those in Parte veynte y cinco; even the dedication to Pérez de Montalbán has the same wording. No, this is yet another fraudulent volume. This time I think the preliminaries are the work of Manuel de Sande; some of the contents are certainly his.

The volume opens with Por la puente Juana, which ends on C3r, at the foot of which is the catchword CE-. On C3v begins Celos con celos se curan, which continues until E8v. There is no foliation, but the two plays cannot be separated, and so must have formed part of yet another collected volume of plays. Here is a brief list of the types of Por la puente Juana:

The same types are used in Celos con celos se curan: the damaged sorts in De Lope de Vega Carpio (R5) are very noticeable. Some of the designs which we first saw in El burlador de Sevilla show signs of wear here. This is particularly true of the text italic IT2. Sande had replaced R4, his text roman, but a few sorts from it had managed to creep into the replacement.

The third play in the volume is Lanza por lanza de Luys Almanza, which begins with signature D, folio 21, and so must have been printed as the second play in a volume, not the third. It is followed by five plays which seem to make up a unit with it, then by four plays which begin with folio 1 and signature A in each case. If we examine the first of these four plays (it is the «Lope» version of El médico de su honra), we see from type and layout that it is the real first play of the group immediately preceding it. Naturally, foliation and collation (1-20, A-B8 C4) also fit, which is not so with the remaining three. The play also has a large woodblock which is used in three more of the plays in the group (El sastre del Campillo, Julián Romero and Los Vargas de Castilla), and in Celos con celos se curan. The complete group is as follows: El médico de su honra, A- B8 C4; Lanza por lanza de Luys Almanza, D-E8 F2; El sastre del Campillo, G-I8; Alla darás rayo, K-L8 M2; La selva confusa, N-O8 P6; Julián Romero, Q-R8 S6; Los Vargas de Castilla, T-X8. Foliation runs continuously throughout these plays, except for some confusion, appropriately enough, in La selva confusa.

The remaining three plays in the University of Pennsylvania copy of Parte veinte y siete are Los milagros del desprecio, El infanzón de Illescas, and El milagro por los zelos. Damaged types in the headlines of the first two indicate that they were produced by the same printer as the large group just listed. In the case of El infanzón de Illescas there is further evidence from a woodblock. Professor Carol Kirby of Purdue University has drawn my attention to a variant impression of this play (B. L., 1072.1. 12[2]). The play ends with an odd leaf (A-B8 C4 D1) and the printers evidently set the last leaf twice to save press time. The setting represented by the B. L. copy has the woodblock we have seen used in El médico de su honra and in other plays of Parte veinte y siete. The other setting, represented by the University of Pennsylvania copy, has no block, but the other twenty leaves are identical, and all the type used can be associated with Sande. The odd leaf D suggests that the impression was planned as a suelta.

In the case of the University of Pennsylvania's Parte veinte y siete, we can make a comparison with another copy preserved in Barcelona. I have not seen the Barcelona copy, but Signora Profeti's description shows that it differs in the final play27. Professor Kirby tells me that they are otherwise the same. The fact that they vary in one play corroborates what was said above: made-up volumes of this kind never existed in large numbers, and even such copies as survive will not necessarily be the same, probably because they were made up to get rid of small quantities of unsold stock.

The Biblioteca Nacional has two fragments which seem to confirm the hypothesis concerning Parte veinte y siete: one contains Por la puente Juana and Celos con celos se curan (R-i-57); the other contains the group of seven plays beginning with El médico de su honra and ending with Los Vargas de Castilla (R-23244)28.

None of these nine plays appears to have been printed before, and only Por la puente Juana is definitely by Lope. Celos con celos se curan is Tirso's (is this significant?). Autograph manuscripts for El sastre del Campillo and La selva confusa survive, in the hands of Luis de Belmonte Bermúdez and Calderón, respectively; Morley and Bruerton list the remainder among «doubtful» Lope plays29. The existence of the two autograph manuscripts will make it possible to draw some conclusions about the transmission of the texts involved, but as they are not likely to have been used as compositors' copy, any light they throw on the textual transmission of El burlador will at best be indirect.

Before I leave Parte veinte y siete, I should like to draw attention to what may be another fragment of one of the dismembered volumes which make it up: an edition of Pérez de Montalbán's El príncipe de los montes (alias A lo hecho no hay remedio). This fragment was once in the collection of Professor E. M. Wilson, and is now in the University Library, Cambridge. Here is a brief typographical description:

There is not much doubt about the printer of this item: in type used it is nearest to the El médico de su honra group. Its layout does not correspond exactly with any of the established groups, but it is signed Y-Z8 Aa4, and foliated 147-66. This would allow it to fit perfectly after Los Vargas de Castilla, which ends on folio 146 with signature X30. El príncipe de los montes could also have been the eighth play in one of the other volumes of which we have fragments, including the Burlador one. On the other hand, if the date of the first known performance is used as a guide (although it is not a reliable one), then we can postulate yet another volume, presumably printed in 1634, of which this is the only fragment so far identified31.

This search for pieces of a jigsaw has so far turned up more puzzles rather than more pieces. All the jigsaws have pieces missing, and they have been mixed up as well. Here is a tentative list of them:

To these may be added Olvidar para vivir and El hijo por engaño, which may have been printed by Sande in the late 1620s, and also Los milagros del desprecio and El infanzón de Illescas, apparently printed by him at the same time as the third and fourth volumes above. Like so many others of these plays, they had not been printed before.

Manuel de Sande, known to comediantes only from his name on the Tirso Primera parte, emerges as a figure of considerable importance in the publication of Golden-Age drama. His signed productions are regrettably rare, and in addition to those already mentioned in this article, I have been able to discover only the following:

|

Alonso de Castillo Solórzano, Escarmientos de amor moralizados, 1628 (Library of The Hispanic Society of America, and elsewhere). No other edition is recorded. Juan Fragoso, De succedaneis medicamentis, 1632 (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, and Salamanca University Library). This is the only Sande item which had definitely been printed before; editions of Madrid 1575 and Madrid 1583 are recorded, although no copy of the 1583 edition is known at present32. |

Apart from Sande in particular, this study has also uncovered some evidence for the importance of Seville in general as a centre of unauthorized printing. While checking editions of Castillo Solórzano, I was struck by the number of them ostensibly printed by Cormellas of Barcelona about 1630. I examined a facsimile of one of these, Los amantes andaluzes, and on folio 182v noted what appeared to be the small woodblock used by Simón Faxardo in Las dos vandoleras. Of course it is hard to be certain about small blocks when one is comparing a facsimile of one book with a photograph of another: one would need to compare the originals in the Biblioteca Nacional33. In addition, confirmation would have to be sought from typographical evidence. There is good reason to suppose, however, that some, perhaps many, «Barcelona» books of this period are really Seville, especially if they were printed once the ban was being enforced.

Interestingly enough, Seville retained its dubious reputation long after the ten-year ban on novels and plays had been removed. In 1682 Don Juan de Vera Tassis complained that almost all the plays printed in Seville for the Indies market were falsely attributed to Calderón, whose reputation was then what Lope's had been fifty years earlier34. There is also conclusive typographical evidence that at least some of the Parte sexta of the Comedias escogidas series was printed in Seville about 1675. This edition's place and time of printing were for long thought to be Madrid, 1649; the date was later modified to 1654. «Madrid» is certainly not the whole story, and the date is twenty years off at least35. I mention this book because it contains the second edition of El burlador de Sevilla36