Cervantes : Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America

Volume XXII, Number 1, Spring 2002

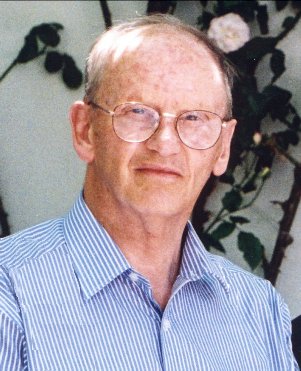

E. C. Riley, 1923-2001

THE CERVANTES SOCIETY OF AMERICA

President

EDWARD H. FRIEDMAN

Vice President

JAMES A. PARR

Secretary-Treasurer

THERESA SEARS

| ELLEN ANDERSON | MW VALERIE HEGSTROM |

| MARINA BROWNLEE | NE DAVID BORUCHOFF |

| ANTHONY CÁRDENAS | PC HARRY VÉLEZ QUIÑONES |

| MICHAEL MCGAHA | SE SHERRY VELASCO |

| ADRIENNE MARTIN | SW AMY WILLIAMSEN |

CERVANTES: BULLETIN OF THE CERVANTES SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Editor: DANIEL EISENBERG

Managing Editor: FRED JEHLE

Book Review Editor: WILLIAM H. CLAMURRO

| JOHN J. ALLEN | MYRIAM YVONNE JEHENSON |

| ANTONIO BERNAT | CARROLL B. JOHNSON |

| PATRIZIA CAMPANA | FRANCISCO MÁRQUEZ VILLANUEVA |

| PETER DUNN | FRANCISCO RICO |

| JAIME FERNÁNDEZ | GEORGE SHIPLEY |

| EDWARD H. FRIEDMAN | ALISON P. WEBER |

| AURELIO GONZÁLEZ | DIANA DE ARMAS WILSON |

Cervantes, official organ of the Cervantes Society of America, publishes scholarly articles in English and Spanish on Cervantes' life and works, reviews and notes of interest to cervantistas. Twice yearly. Subscription to Cervantes is a part of membership in the Cervantes Society of America, which also publishes a Newsletter. $20.00 a year for individuals, $40.00 for institutions, $30.00 for couples, and $10.00 for students. Membership is open to all persons interested in Cervantes. For membership and subscription, send check in US dollars to THERESA SEARS, Department of Romance Languages, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC 27402-6170 (tasears@uncg.edu). Manuscripts should be sent in duplicate, together with a self-addressed envelope and return postage, to DANIEL EISENBERG, Editor, Cervantes, Excelsior College, 7 Columbia Circle, Albany, NY 12203-5157 (daniel.eisenberg@bigfoot.com). The SOCIETY requires anonymous submissions, therefore the author's name should not appear on the manuscript; instead, a cover sheet with the author's name, address, and the title of the article should accompany the article. References to the author's own work should be couched in the third person. Books for review should be sent to WILLIAM H. CLAMURRO, Division of Foreign Languages, Emporia State University, Emporia, Kansas 66801-5087 (clamurrw@emporia.edu).

Copyright © 2002 by the Cervantes Society of America.

—5→

I first met Ted in September 1966 as I had been appointed Junior Lecturer, in his absence, in his department at Trinity College Dublin. He had spent the previous year in the United States, teaching at Dartmouth College. We used to joke afterwards that one of the conditions of employment had been marriage to the professor! Be that as it may, after 20 years in Dublin, Ted was appointed to the Chair of Hispanic Studies at the University of Edinburgh and in 1970 came to live in Scotland. We were married the following year. Ted was 47, I was 27.

Looking back now, after 30 years of happy marriage -one that went from strength to strength- what can I write about the man who was so dear to me? Those early years as colleagues in Dublin have blurred while the images of family life have sharpened. His delight at the birth of our children, Nick and Hannah, was followed by pride and interest in their development and choice of careers.

I think Ted saw himself primarily as a writer. He was, of course, also a teacher and he enjoyed both the teaching and the company of his students. After retirement he looked forward to the teaching opportunities which came his way, especially when they involved new places: Japan, China, Brazil. And he kept in touch with students as much as he could.

After his cardiac operation in December 2000, when a long

period of recuperation lay ahead, I suggested that he might take

up watercolour, in which he had expressed an interest before he

had retired. But now that the opportunity was there, he said that

he didn’t think it was appropriate. And when I asked him why, he

said «Because I write. It’s what I do»

.

And it’s true. Ted had always written. Age 12 and 14, he wrote

accounts of his transatlantic journeys home to Cuba from school in

—6→

Cervantes

Bristol. Letters home of course. He wrote an account of his school

days at Clifton and another of his war-time experiences in the

Navy 1943-45. They were never intended for publication but to fix

events in his mind and to send to his family on the other side of

the Atlantic Ocean. (He was fifteen when war broke out and did

not see his family for the next seven years). Looking back in 1948

on those years at school and in the Navy, he was puzzled that they

seemed better than those spent at Oxford. He felt that it should

have been the other way round. «Of course they were not better

in every way -intellectually they were much less satisfactory. But

the other days were happier, which is what counts».

In contrast

stood «the confused, loose va-et-vient, the discordant (and beguiling)

academic clap-trap of an University»

. Many other undergraduates

of that generation felt similarly detached.

He tried writing fiction -short stories- but was dissatisfied

with his efforts. It was narrative which interested him more than

poetry or drama and it was Cervantes who became the object of

his life-long fascination. The Laming Travelling Fellowship at

Queen’s College enabled him to go to Madrid in 1948-49 to research

literary theory of the Renaissance. While he was there he

was invited by Walter Starkie to give a talk to the British Institute.

He chose to speak about James Joyce, whom he greatly admired.

In his concluding paragraph he writes: «In another age Joyce

would have been a Cervantes, a Rabelais or a Goethe...»

Those familiar with Ted’s writing will recognize the parallels drawn between the sixteenth and the twentieth centuries which, I think, are one of the hallmarks of his approach. His talk showed a real understanding of Joyce’s technique and also illustrated wide reading on his part. Joyce remained a favourite and although Ted was not a collector, he did acquire editions and translations of Ulysses. He read widely all his life, serious fiction always but also popular and scientific titles. (On his table when he died were American Dream, Philip Roth, Genome by Matt Ridley, and the first of the Harry Potter series, by J. K. Rowling).

The sporting interests he had when young -rowing, then squash- were stopped by a slipped disc. Outside work and family, his main interest was the cinema. He was a real connoisseur and always knew what was on, and invariably went. (He was rather —7→ proud of his video collection too). A convivial host, he was a dabhand at mixing cocktails and ice-cream making, having discovered a machine which made the latter in minutes.

Ted was, by his own admission, very much a creature of habit. Sunday mornings were invariably devoted to letters, as he was a loyal correspondent as well as a thoughtful friend. And letters came flooding in after his death, confirming my feelings about him and affirming his life -a wonderful person to know, great fun to be with, such a gentle man... and such a modest one.

In his journal in Cuba in 1948, seeing his parents and his home

again after such a long absence, he wrote «'Hold to the here, the

now, through which all future plunges to the past', says Joyce. I

am holding»

. And then he added later: «So I thought and did, but

it slipped through just the same»

.

There was about Ted a sense of adventure and a kind of innocent enjoyment of life, which was tempered by an awareness of its transience. At his funeral, our son Nick read a Borges sonnet, «Everness» (from El otro, el mismo). I think he would have liked that.

Judy Riley

13 March 2002

When Judy Riley phoned me around 6 p. m. on the first Wednesday in March 2001, I guessed what she was going to say before she said it, first, because it was odd that she should have called my office number, and second, because I had been vaguely apprehensive about the outcome of Ted's major heart surgery in mid-December. The news of his death gave me the kind of shock that you get when you sense part of your life has dropped away. Ted was the director of my Ph. D. thesis, on which I began work at Trinity College, Dublin in 1962. After I got the doctorate, then jobs in British universities, we remained in regular contact and became good friends; we regularly exchanged news and views about Cervantes, and coincided at conferences. On one such reunion, in —8→ Cervantes Santander, while I babysat my daughter in the hotel, the Rileys and Ted's sister, accompanied by my wife, went to the local casino, where Françoise recouped all the money she had lost by leaving her wallet in the bar where we had all had tapas and wine just a few hours before. I mention this because losing and winning money together in gambling joints is clearly indicative of friendship that goes beyond professional ties.

However, it wasn't just the loss of an old friend that shook me. Ted Riley's direction of my thesis and his scholarship were -still are- the single most important intellectual influence upon me so far as Hispanism is concerned; and that influence grew over the years. For instance, the first time I read Cervantes's Theory of the Novel -I mean, really read it, taking notes, analysing the structure, following through the threads of argument- was in 1993; obviously I had read it in more superficial ways on previous occasions. That was the first time that I really understood what a big book it was, and how it related to other seminal books on the Spanish Golden Age written within about a decade of its publication. How and why it influenced me are attested in the introductory chapter of my Cervantes and the Comic Mind of his Age.

As a thesis supervisor Ted was most effective, generous with

his time and attention, positive and encouraging, actively concerned,

good at pulling you back into line when you had strayed.

At first I found him, not remote exactly, but reserved: tall, neat,

thinning hair, freckled complexion, somewhat shy, with a clear

penetrating gaze and an accent and good manners that reminded

me of the epithet «English gentleman». That he had a more laid

back and down-to-earth side -a taste for the songs of Julie Andrews,

stiff cocktails, and other pleasures of the common man-

only become apparent to me later; it is hilariously reflected in the

bizarre and informative variety of examples that he gives of the

pervasive allusions to Don Quijote and Sancho in modern popular

culture at the beginning of his article «Don Quixote: From Text to

Icon», published in a special issue of Cervantes (winter, 1988).

However, at the time, the apparent diffidence added force to the

occasional manifestations of disapproval. On one occasion when

I arrived late for our periodic and frequent supervisions at his

rooms in Trinity College to discuss one of my contributions on

—9→

Cervantes, he sat silent for a minute, removed the pipe to utter

«You're late»

, reinstated the pipe, and remained withdrawn and

disapproving for some considerable time. On another occasion, I

remember the comment «This is turgid and arid in the extreme»

about one of my more diffuse essays. I fancied my prose style in

those days; and that, combined with the contrast between the

crushing dismissiveness and Ted's habitual courtesy, had a salutary

and long-term impact. Anyone who may have noticed a

tendency towards sober laconicism in my writing now knows the

historic reason for it. He taught me precision in the use of words

too. In one essay I made some comment about Don Quijote's

pedantic correction of one of Sancho's solecisms. «Pedantic in

this?»

he wrote in the margin (because, in its context, the correction

was justified). He taught by example, since he was a model of

lucidity and precision in his own scholarship. For a good example

of it, see his distinction between what the critics traditionally say

that Cervantes says in the passage about the «pensamientos escondidos

del alma»

, in the prologue to the Ocho comedias, and what

Cervantes actually does say. This comes at the beginning of his

essay «The Pensamientos escondidos and Figuras morales of Cervantes»,

in Homenaje a William L. Fichter (1971).

The most important contribution that he made to my thesis, which was supposedly on «The Ideas of Art and Nature in the Works of Cervantes», was in pointing out to me, after I had spent two agreeable years exploring the dichotomy of Art and Nature in the Western tradition from Plato onwards, including just about everybody but Cervantes, that this omission was unacceptable. By then I was living, and drafting the thesis, in Cardiff. Ted wrote to tell me that I had strayed too far from Cervantes, and that it would be better if I came to Dublin for a talk about it. He could have said what he had to say by letter; yet he obviously recognised that to get the lost sheep properly well and truly back in to the fold, the message had to be communicated forcefully and directly. The tactic worked; and I learned another big lesson, namely that a thesis (book, article, lecture, whatever) has to have a thesis.

After the doctorate, we had our differences, Cervantine and

never personal; these were the kind of differences that arose between

Don Quijote and Sancho. Ted tended to believe that,

—10→

though the object in question was undoubtedly a windmill considered

from a historical viewpoint, the fact that posterity had seen it

as a giant was part of its potential significance. I tended ploddingly

to insist on the literal and historic sense. My habit of referring in

my Cervantine publications to his own, and of taking these as a

starting-point for a line of enquiry that differed significantly from

his views, mildly irked him; and on the ms. of an article that I submitted

to a journal in the early 1990s, he wrote, while strongly recommending

publication: «I could wish that Dr Close would stop

using my work as a means of getting lift-off»

. I replied by sending

him a cheery postcard of the Grand Canyon, after a family holiday

in the California national parks, saying that it wasn't my fault if

Cervantes's Theory of the Novel was a great monument of twentieth-century

Cervantine criticism, and an inescapable reference-point

for anyone working in that area. Ted thought I was trying to flatter

him; but after he had seen me render homage to his book, in the

same terms, in print, on subsequent occasions, he realised that I

meant it seriously. He never subsequently reacted to my mode of

getting lift-off with other than good-humoured magnanimity.

The funeral was at a crematorium in south Edinburgh on a sunny day in mid-March, and to my southern English mentality, Edinburgh seems as remote as Reykjavik, Spitzbergen, or Thule. Hence I was surprised to see how many people were there, and in particular, old friends from my Dublin days. Amongst ex-pupils and colleagues of Ted were Edwin Williamson, who gave the funeral address, Dan Rogers, Eamonn Rodgers, James Whiston, and also me. I had travelled far to be there, but others had travelled further. We all had the same basic motive for going, with individual inflections in each case. As far as I was concerned, Ted was a role-model for all the reasons mentioned above, and for a further one: generosity of spirit. He was always zestfully curious about new trends and horizons, encouraging towards up-and-coming scholars, zealous in keeping up with old friends. I often have had occasion since 1962 to be grateful for his generosity towards an old pupil. He was not just a great cervantista but a great man. Que aunque la vida perdió, dejonos harto consuelo su memoria.

Anthony Close

—11→

Ha muerto E. C. Riley, Edward Calverley Riley, Ted, para sus amigos. Ha muerto en Edimburgo, en cuya universidad enseñó y donde vivió con su familia, en un pueblo de las afueras. Por vicisitudes del trabajo de su padre, que era ingeniero mecánico, había nacido en México, D. F., y se había criado en Cuba. Se educó en Clifton College, Bristol, y cuando el padre se jubiló fueron a vivir todos a Cornualles. Después entró en Oxford University, donde obtuvo su licenciatura, aunque sus estudios fueron interrumpidos por la guerra mundial.

Su primer puesto de enseñanza fue en Trinity College, Dublin, y allí pasamos nuestra primera temporada juntos. Años después obtuvo la plaza en la Universidad de Edimburgo, aunque salió varias veces, invitado por diversas universidades, entre ellas varias norteamericanas. Recuerdo con nostalgia la temporada que estuvo en Dartmouth College, porque yo entonces enseñaba en Smith College, a corta distancia al sur. Los fines de semana solía venir a visitarme, y charlábamos de omni re scibile.

En una de esas largas y amistosas charlas le propuse que formásemos entre los dos un equipo de los mejores cervantistas del momento, y que cada uno de los escogidos estudiase un aspecto de la obra cervantina designado por nosotros dos. La idea le agradó, y el resultado de esa charla, con el pasar del tiempo, fue la Suma cervantina. Claro está que por su cuenta Ted llevó adelante una selecta obra cervantina ejemplar y su Cervantes's Theory of the Novel es una obra clásica sobre nuestro clásico mayor.

A Ted le gustó viajar, primero solo y después con su encantadora mujer Judy. A ella la conocí un verano que las dos familias pasamos juntos en Suances, en la costa santanderina. A menudo nos encontramos en España y una vez, inesperadamente, nos encontramos en un lugar de La Mancha. Nos reímos mucho.

En sus últimos momentos Ted tuvo tiempo para ojear las pruebas y escribir el prólogo de su último libro: La rara invención. Estudios sobre Cervantes y su posteridad literaria, que publica la Editorial Crítica. Con la muerte de Ted el hispanismo ha perdido uno de sus más sólidos pilares y yo un gran amigo. Gloria in excelsis Deo.

Juan Bautista de Avalle-Arce

—12→

Faltan palabras para decir lo que Edward C. Riley significa en la historia crítica del cervantismo. La muerte le sorprendió frente a las pruebas de la colección de sus obras que edita Francisco Rico. Es el mayor tributo que se le puede hacer a un crítico de integridad absoluta, de amplia cultura literaria, visionario sin pretensiones, caballero en sus juicios sin condescendencias. E. C. Riley es y será uno de los más queridos, respetados y admirados cervantistas del siglo XX, maestro y mentor de tres generaciones. Es desde esta perspectiva personal que quiero recordarlo.

Antes de conocernos, comenzó nuestra correspondencia, escasa pero intensa y orientadora para mí. Fue a raíz de mi primer artículo de 1968 sobre la cueva de Montesinos, sugerido por unas frases reveladoras de su primer libro, Cervantes's Theory of the Novel. La aprobación de una autoridad como el maestro Riley legitimizó mi deseo de proseguir con el minucioso y exhaustivo análisis de una docena de capítulos clave de ambas partes del Quijote en Cervantes y su concepto del arte (1975), siempre guiada por el libro de Riley. Sólo que ahora, me atrevía a oponer a su criterio de teoría cervantina de la novela el mío, que tal teoría era más intuitiva que cerebral, y se desgajaba de su estilo metafórico-simbólico-alegórico para pintar personajes e ideas. Osadamente, le hice llegar un ejemplar de mi libro desde Gredos.

Su respuesta apareció en la primera página del Times Literary

Supplement de Londres en septiembre de 1976. Me hacía justicia

desde su criterio teórico-literario sobre la ampliación del episodio

de la cueva de Montesinos. Reconocía mi percepción de varios

niveles temáticos, el más válido el autobiográfico en Argel, apuntaba

que no los había visto todos, aun admitiendo que había ahondado

yo más que nadie en este episodio, juicio que repitió en 1982

en un artículo «Metamorphosis, Myth and Dream in the Cave of

Montesinos», en Essays on Narrative Fiction in the Iberian Peninsula

in Honour of Frank Pierce. Por otra parte, mi caracterización de Zoraida

en la historia del cautivo, le convencía enteramente: «she will

never be the same again»

. En cuanto a mis interpretaciones, a pesar

de que sonaban a teología místico-crítica, se basaban en estricto

análisis textual con el cual no se podía querellar. Me negaba, sin

embargo, credibilidad sobre mi percepción negativo-alusiva del

Caballero del Verde Gabán, considerado hasta entonces modelo de

—13→

caballero español. Me había dejado llevar demasiado por los sentidos

ocultos en metáforas, simbolismos y colores. ¡Yo que confiaba

haber desentrañado un aspecto fundamental del novelar cervantino...!

No pensaba escribir más sobre Cervantes, pero su juicio me indujo a seguir con el análisis textual a fondo, como el que le había gustado sobre Zoraida, en busca de caracterizaciones incontrovertibles y, sobre todo, de la aprobación del maestro.

Dos años más tarde, en septiembre del 77, tras el congreso en

Toronto, me escribió que sentía que no hubiera estado presente:

«You might have been amused to find me symbol-hunting like

mad in my ponencia! I called it 'Simbolismo conflictivo en D. Q.

Pte. II, cap. 73'. It certainly owes something to your book»

. El

artículo salió en el Journal of Hispanic Philology, invierno de 1979,

con el título de «Symbolism in Don Quixote, Part II, Chapter 73».

Fue en Madrid en 1978, en el Primer Congreso Internacional sobre Cervantes, que tuvo lugar nuestro primer encuentro, muy cordial y muy breve por la aglomeración de cervantistas y admiradores que se disputaban saludar al maestro.

La segunda vez fue en Washington D. C., en la Biblioteca del Congreso, en ocasión de la celebración del Cuarto Centenario de La Galatea, 1985. La conferencia de Riley se titulaba «Don Quixote: The Power of the Image». En mis apuntes leo: «verbal discourse», «visual reproductions», «psychology of perception», «visual alertness», «illusion, delusion, reality», «duality of perspectives, splintered with considerable complication», «problem of identification», «verbalization of experience», «fantasy in moderation, enhancing grasp of reality», «deeper meanings», «moral truths». Me abandonó el terror. Mi conferencia se titulaba «Cervantes, the Painter of Thoughts».

El tercer encuentro tuvo lugar en Kentucky en abril de 1990. El profesor Joseph Jones me había pedido organizar la sesión sobre Cervantes en la Kentucky Foreign Language Conference. Para asegurar su éxito le pedí a Riley que participase. Pese a contar con un tiempo muy justo entre dos precipitados viajes, aceptó la invitación. Comprendí que lo hacía por no decepcionarme y para asegurar mi éxito con su presencia. Durante la cena, me dijo que le había gustado mi caracterización del Caballero del Verde Gabán, —14→ reelaborada en Cervantes the Writer and Painter of Don Quixote, salido dos años antes. Es entonces que me pidió de tutearnos, siendo tan buenos amigos. ¿Cómo se tutea a un ídolo?

El cuarto y último encuentro fue en marzo de 1999, en su casa

de Westholme al sur de Edimburgo. Ignacio había sido invitado a

conferenciar en los centros hospitalarios de Aberdeen al noreste y

de Newcastle y Sunderland al sureste de Edimburgo. Contábamos

con seis días escasos. Pensábamos dar un salto entre ambos compromisos

para ir a casa de Ted a saludarle. Imagino que le pareció

un tour de force tal precipitación y nos ofreció de alojarnos en su

casa como centro de comunicaciones, alegando que estaba muy

solo y aislado. ¿Lo dijo para que quisiéramos aceptar? ¿Para facilitarnos

los desplazamientos? ¿Por ambas razones? Lo cierto es que

pasé tres días inolvidables hablando de Cervantes, el autor que

«ambos queremos tanto»

.

Le traje un pequeño calendario-pisapapeles permanente de mármol que le fascinó como a un niño con un juguete nuevo. Y es que nunca perdió el don de maravilla de la niñez a través de los años. Judy, su extraordinaria esposa y compañera, diseñadora de jardines, artista en su profesión, como en la cocina, nos regaló con una cena de bienvenida. Nos sentimos en familia.

También le entregué a Ted mi último artículo publicado, «Luscinda y Cardenio: autenticidad psíquica frente a inverosimilitud novelística», aparecido ese año en «Ingeniosa invención», el homenaje a Geoffrey Stagg. Lo quería leer antes que nos fuéramos. El segundo día de la ausencia de Ignacio, cuando me desperté, Judy había salido para su trabajo. Ted contemplaba su jardín diseñado por ella. Había terminado de leer mi artículo. Me preguntó que si quería desayunar un huevo. Él iba a tomar uno. Me hizo una tortilla y un té sin dejar que yo le ayudara. Era una inequívoca aprobación sin palabras. Me emocionó. Me dijo que le gustó mi visión de Cardenio pero, con su acostumbrada integridad crítica, dudó de la fortaleza que yo atribuía a Luscinda. Nadie la había visto así antes, sino como objeto de la caracterización de Cardenio. Yo descubría pensamientos y emociones en los silencios y acciones de Luscinda y, para postre, en el simbolismo de su espectacular atuendo en ocasión de su boda forzada. Me defendí. A mis lectoras, Luscinda les había parecido muy auténtica personalidad femenina.

—15→

Me preguntó qué estaba escribiendo. Le dije que preparaba

una ponencia en ocasión del retiro de John J. Allen y que al prepararla

había descubierto una fusión entre Lope de Vega y Jerónimo

de Pasamonte en el «Retablo de Maese Pedro», episodio que creía

ocultaba el misterio de la autoría del apócrifo por Avellaneda. Su

reacción fue de sorpresa: el apócrifo estaba demasiado mal escrito

para ser de Lope de Vega y demasiado bien para ser de Jerónimo

de Pasamonte. Meses más tarde me enviaba por correo urgente su

último artículo que acababa de salir, «Sepa que yo soy Ginés de

Pasamonte»

. Había quedado intrigado. Sentí que quería evitar que

me extraviara. El resultado de ésta mi postrera investigación saldrá

próximamente en Cervantes.

El tren que nos apartó de los Riley repercutió en mi espíritu como símbolo clásico al revés de la separación definitiva. ¿Otra vez los símbolos? Pero ¿qué son sino relámpagos de la intuición?

En diciembre pasado recibimos una tarjeta de Navidad: «Dentro

de pocos días me operan del corazón y en la primavera de la

cadera»

. La primavera ha llegado. Pero Ted ya no está entre nosotros.

Nos queda su legado de crítica cervantina, y una imagen

luminosa de su generosa amistad. Para mí ha sido norte y guía en

la trayectoria analítica que he seguido en mis trabajos cervantinos.

Helena Percas de Ponseti

I am very indebted to my esteemed friend, Ted Riley, who taught me an important lesson.

I particularly remember and recall a conversation at a Cervantes Society meeting in Washington. He told me that if someone wears a T-shirt depicting Don Quixote, he would be recognized by almost everyone. (This would not happen with a T-shirt showing Faust or Don Juan). It illustrates the universality of Don Quixote; he belongs -with his idealism and altruism- to the entire world.

Karl-Ludwig Selig