«Literature» and the Book Trade in Golden Age Spain1

Don William Cruickshank

University College, Dublin

| If a man were permitted to make all the ballads, he need not care who should make the laws of a nation. |

| (Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun) | ||

Since my intention

in this paper is to put forward what seems to be an original

hypothesis, I feel I must begin cautiously: first, by defining my

terms, and second, by quoting the words of an authority in the

field of bibliography. By placing «literature» in

inverted commas I wish to imply a broader meaning than that

normally accepted; that is, I mean it to include what might better

be described as «sub-literature», work with pretensions

to literature or which takes the form of literature without

meriting the title in its strict sense. By «Golden Age»

I mean that period of political, economic and cultural importance

which could be said to have begun in 1479, when Ferdinand and

Isabella became the undisputed monarchs of a united Spain, and

which ended definitively in 1700 with the death of the last

Hapsburg king, Charles II. My bibliographical authority is

Steinberg, in the introduction to his Five Hundred Tears of

Printing: «Neither political,

constitutional, ecclesiastical, and economic events, nor

sociological, philosophical, and literary movements can be fully

understood without taking into account the influence which the

printing press has exerted upon them»

2.

My intention is to examine a literary movement in terms of the

influence upon it of the printing press. Economic events are also

crucial to the examination.

While Spain's economic impact on the rest of Europe was considerable throughout much of the Golden Age, the country's prosperity was short-lived: Spain's first official bankruptcy was declared as early as 1557. Indies treasure imports reached their height (42,221,835 ducats) in the years 1591-95. By 1631-35 this figure had fallen to less than half, and by 1656-60 to less than a tenth3. Some sections of the Spanish economy, notably agriculture, were never truly prosperous. As historians have shown, Spain's political and military power were linked to her imports of bullion, and as the latter declined, so did the former4. The zenith came in the reign of Philip II, although Spain still seemed a formidable enemy to her neighbours as late as the first half of the reign of Philip IV. The battle of Rocroi (1643), which neatly bisects the reign of Philip IV, also marks the end of any lingering Spanish claims to be the major power in Europe, for in it the previously invincible Spanish infantry was decisively defeated.

The high point of Spain's cultural importance comes after these other high points: in the first half of the seventeenth century. Even as late as Rocroi, when Lope de Vega, Góngora and Cervantes were dead, Quevedo, Calderón, Tirso de Molina, Gracián -and, for that matter, Zurbarán, Velázquez, Alonso Cano and Murillo- were still alive. Tirso was no longer active, and Quevedo had only two years to live (although they were important years, in which he finished his life of Brutus and prepared other works for posthumous publication); but Gracián and Calderón between them had over fifty years of productive life, including many major works, still ahead. Moreover, a glance at any suitable bibliography shows that the dead authors lived on in successive reprints of their works throughout the seventeenth century (and, for that matter, well into the eighteenth).

Given these facts,

the discovery that no major Spanish authors were born in the

seventeenth century should come as a surprise. Literary figures do

not arrange to be born at times convenient for literary historians,

but in this case one almost feels that they were trying to be as

helpful as possible. If it is accepted that «major

authors» means «those with a lasting international

reputation», then there is only one trivial exception:

Gracián, born on 8 January 1601. We must surely be tempted

to wonder why none of the authors born after 1600, and who received

their literary formation during the height of Spain's cultural

Golden Age, was able to emulate his elders5.

The bald statement that «all major Spanish

authors of the Golden Age were born in the sixteenth

century»

sounds too sweeping, and does not answer the

question, but it may indicate where the answer is to be found.

Printing arrived in Spain in the early 1470s, but although at least twenty-nine towns had seen presses set up in them before 1521, the impact of the press on the book trade and particularly on the status of the author was a very gradual one6. Until printing was invented, no author made a living from selling his work to the general public. This situation held good in Spain until at least 1600, and even then, patronage was still an important source of income for most authors. For the century before printing came to Spain, Spanish literature had tended to be monopolized by members of the great noble houses: not only did they often write it, but only they could afford to pay for it. Throughout Europe, printing brought first the lower gentry and eventually the middle and lower middle classes into contact with written literature; as writers and, perhaps more important, as purchasers. This gradual, but eventually huge growth in the size of the reading public also produced a slow but significant change in the concept of literary reputation. The slowness of manuscript transmission had meant that a widespread reputation could take decades to acquire. The press could make an author famous overnight7.

The widening interest in literature stimulated an interest in literary theory. In Spain's case, the Council of Trent contributed to this interest, because of the Council's concern at the effect of the printed word on the growing reading public8. As every hispanist knows, there were different theories. The dispute between uso (established practice) and arte (Aristotelian precept) took on a moral dimension, thanks partly to Trent and partly to some confusion about what Aristotle meant by catharsis (in the event, the neo-Aristotelians tended to confuse catharsis with the Horatian idea of combining pleasure with profit). Another dispute involved the styles termed conceptismo and culteranismo, which have been described as appealing respectively to the reader's intellect and to his senses. The general public seldom cares about literary theory, whether it involves ethics or stylistics, but circumstances in Spain seem to have been exceptional: the exponents of the different theories often derided each other publicly and with unusual bitterness; as I shall argue presently, Madrid was unusually small for a major cultural centre, so that the writers were much more likely to be familiar figures to their immediate public; and just as the new and exciting possibilities of literary fame were beginning to impinge on authors, one of the best known, Lope de Vega, published a treatise which virtually tells the intending playwright how to become a roaring success with the public (I refer to his Arte nuevo de hacer comedias en este tiempo of 1609). As its title implies, the Arte nuevo is Lope's contribution (partly tongue-in-cheek, partly serious) to the arte / uso debate; his argument is that established practice (uso) has become a new art-form (arte nuevo). Lope's fecundity as a playwright is well known, and perhaps the play in performance also made Spain exceptional, in the extent to which it brought literature even to the non-literate public. Of course there were playhouses in other countries, and England must have run Spain a close second in this respect; but I suspect that only Spain offered her unlettered public such a range and quantity of dramatic literature.

As we know from writers like Rojas Villandrando, even the most rural and otherwise culturally deprived parts of Spain had access to literature in the shape of plays and other oral forms; but at the same time Spain became in cultural terms a very centralized country. In the sixteenth century, especially before the establishment of a fixed capital, one could find major writers living and working almost anywhere in Spain. Soon after 1600, on the other hand, Madrid became an obligatory Mecca for writers, whether they were born in Alcalá, like Cervantes, or in Córdoba, like Góngora. What is striking about this is, first of all, that Madrid, unlike London in England, was only one of a large number of centres where books could be printed; and second, that for most of the Golden Age, Madrid was not even the largest city in Spain. Gracián, who lived and wrote in Aragón, is once again the only major exception to the general rule. What it means, I suggest, is that Madrid is unusual if not unique as a cultural capital in seventeenth-century Europe. With a population of only 37,000 in 1597, and less than 100,000 as late as 1650, it must have been the smallest cultural capital in Europe in proportion to the country's total population (about 8,000,000)9. We need not wonder, given this concentration of activity in Madrid, that it was such a centre of cultural ferment in the golden half-century of 1601-50.

When I first thought of looking at Spanish literature in terms of printing, the obvious starting-point seemed to be graphs of book-production (using the word «book», at least to begin with, in its widest possible sense). The difficulties here are vast and, as we shall see, unlikely to be overcome in the near future. There is no STC, no general catalogue for seventeenth-century Spanish books, or even for Madrid books. There are several catalogues for other major cities (none of them recent), and there is Pérez Pastor's Bibliografía madrileña, which goes up to 1625. There are catalogues of two large collections of seventeenth-century Spanish books:

that of the Hispanic Society of America and that of the British Library10. That of the British Library is the larger in terms of numbers, but it is less carefully compiled: it certainly contains a few entries which belong in the sixteenth century, and possibly a substantial number of eighteenth-century books under the incorrect guess-date [1700?]. If we rely on books with both date and imprint, we find that Madrid appears to account for about forty per cent of Spain's seventeenth-century output (in terms of items only). If we regard Pérez Pastor's list of dated Madrid items for 1601-25 as complete (there are 1,441), then the British Library has a sample of about a third, which is reasonably substantial11. If we then draw a graph of this British Library sample, we find that it corresponds in shape to a graph produced from Pérez Pastor's figures. Encouraged by this correspondence, we can continue the graph of the British Library's dated Madrid holdings up to 1700, and hope that the correspondence remains valid. (Readers will at once realize that there are a great many «ifs» in this graph; in fact, it closely matches a graph of dated Madrid holdings in the Library of the Hispanic Society of America; but as will presently become obvious, I do not intend to rely on these graphs: on the contrary). To this graph we can add the supposedly complete graphs for Seville and Valladolid, both major printing centres, and for Toledo, a minor centre.

I have arranged the graphs in five-year periods to show trends rather than annual variations. Once we realize that the extraordinary «boom» in Valladolid's first five-year period is due to that city's having been the temporary capital of Spain from 1601 to 1606 (and that it therefore matches a corresponding «low» in Madrid), we can see that all four graphs have a distinct common feature: an irregular but notable rise early in the century (except for Seville, for the first quarter of the century), followed by a dramatic fall in the decade 1626-35, a fall from which none of the cities wholly recovered. The graphs are dramatic enough, but the five-year arrangement disguises the fact that, in very bad individual years, Madrid production apparently fell to as little as thirty per cent of the «high» of 1623 and 1624 within ten years.

Cervantes had died in 1616, Góngora was to die in 1627. Yet the decade 1626-35 was productive enough for Lope, Calderón and Quevedo, not to mention many other lesser writers. Why is this activity not reflected in the graphs? The ingenuous answer is that on 6 March 1625, the Junta de Reformación recommended that no licences be granted for the printing of novels or plays in Castile: all four graphs are for cities in the kingdom of Castile12. Poetry was not officially affected by the ban, but the suppression of the first collected edition of the poems of Góngora in 1627, amid dark mutterings about dubious religious orthodoxy, could be argued to have affected this genre as well. The ban was lifted (apparently tacitly) in 1635, which might explain Madrid's slight recovery in the years 1636-40. It does not explain why the other cities failed to recover, or why Madrid slumped again, even lower than before.

During this period, of course, the kingdom of Aragón was juridically separate from that of Castile. The central government did not extend the ban to Aragón, possibly because they anticipated resistance from the traditionally strong constituent assemblies of Aragón (Valencia, Cataluña and Aragón proper), possibly because they realized it was not worth taking the trouble to impose the ban on a region where the book-production was only a third of that of Castile. If we go to Zaragoza, the capital of Aragón proper and its nearest major printing centre to Madrid, we find some enlightenment, but not much. We know of Madrid writers who circumvented the ban by going to Aragonese printers, but the graph is still mystifying:

There is a rise in 1626-30 from what looks like the start of a recession, but the figure is hardly more than that for 1611-15, and is completely offset by the drop in 1631-35. If the graph is reliable, then the decade of the Castilian ban is also the worst ten years for printing in Zaragoza. This is a mystery which we are not helped to solve by the absence of a bibliography for Barcelona, although it may be noted that Zaragoza apparently recovered from this slump, unlike the Castilian cities.

Perhaps the first point to be made about the graphs is that they deal only with items: a single-sheet chapbook rates as much as a fat folio. One could, after much labour, produce graphs of the size of books (and by size I do not mean format, but number of sheets). A moment's reflection reveals the futility of this task: the size of a book in sheets tells us nothing about production unless we also know the numbers involved in each edition. Apart from a ridiculously small number of examples, we do not know this, and never shall.

One might think that another way to check the graphs as real indicators of production would be to establish the numbers of printers, booksellers and publishers who were active in any city in each year, and to produce graphs on that basis. In practice, however, there are insuperable difficulties here too. Our convenient modern distinction between publisher and bookseller did not exist in seventeenth-century Spain, any more than it did elsewhere in Europe. Moreover, as we can tell from lists compiled by the Inquisition to keep an eye on outlets for books, the word librero (bookseller) covered everything from what we would call a newsagent to the equivalent of Foyle's13. Some of these libreros operated as wholesalers and retailers. Through the wholesalers, the Inquisition tried to keep a check on the retailers that not even that efficient body could compile lists of: retailers «of no fixed abode», the equivalent of England's «travelling stationers». Some libreros were also publishers, as we know from surviving documents and the recurrence of their names in imprints, preceded by the words a costa de, at the expense of. Unfortunately, the appearance of the expression a costa de Fulano in any given book is of little use as evidence: it means only what it says, namely that the book was printed «at the expense of So-and-so». If So-and-so's name appears in only one book, we cannot conclude that he ran a short-lived publishing business; if it appears twice or three times over a ten-year period, we cannot safely conclude that So-and-so ran a publishing business for ten years. The whole affair is complicated by the fact that printers not infrequently acted as their own «publishers»: there are numerous examples of «por Fulano, y a su costa». The best we can do is compile a list of printers, and even this is fraught with problems, for we seldom know enough about the size of an establishment, or the regularity of its activity, to allow for these factors in compiling the list14.

As I hope to show later, one can reach some general conclusions about the size of Spanish printing-houses. From these conclusions, which are based in part on old inventories, from the inventories themselves, and from other evidence, one can draw inferences about production, and the extent to which it may have been affected by the ban. First, however, I should like to examine the reasons for the imposition of the ban.

As early as 1502,

long before the Catholic Church had to react against the threat of

printed Lutheran and other heterodox propaganda, Ferdinand and

Isabella prescribed a system whereby prelates were to be

responsible for vetting the contents of printed books; they

particularly charged the prelates to prevent the printing of

«cosas vanas, y sin

provecho». They added that the persons selected

to read the books should be paid for their trouble, but not

excessively, lest the printers and booksellers who had to pay them

should suffer too much financial loss15.

One cannot be certain that the phrase «cosas vanas, y sin

provecho» means that the drafters of the law

were attempting to deal with an existing problem; perhaps they were

trying only to anticipate one. In any event they were not

successful, at least in the view of the scholar-printer Miguel

Eguía, who in 1525 complained that Spanish printing-houses

were devoting themselves to producing «vulgar and even obscene ballads, doggerel and

books even more profitless than these»

16.

Although it is

probably unreasonable to expect St

Teresa to be very broad-minded about reading-matter, her

autobiography can be taken as partial corroboration of

Eguía's remarks: in Chapter 2 she refers to her mother's

fondness for chivalresque novels, and describes how that fondness

became in herself an addiction, so that she spent «muchas horas del

dia y de la noche en tan vano

exercicio»

17.

Her autobiography was written in the 1560s, but the events she

describes took place about 1525. Further confirmation is provided

by the Cortes of Castile, which in 1555

petitioned Charles V about books which set a bad example; reference

was made to the harm done by «the reading of books of lies

and vanities like Amadís and all the works that

have been modelled on it, and ballads and plays dealing with

love-affairs and other vanities». The suggested remedy was

that the reading and printing of such works be made an offence, and

that those in existence should be recalled and burned18.

(Even Cervantes, it may be remembered, was willing to spare

Amadís from the flames).

The nearer we get

to the seventeenth century, the more frequent do such denunciations

become. Diego de Estella, who devoted a chapter of his Tratado de la vanidad del

mundo (1576) to «De la vanidad de los

libros profanos del mundo», seems to have felt

that what was not positively sacred was positively profane:

«poesias, mentiras, y

vanidades» are condemned in one breath. Also

condemned are translators of Latin poets and those who read matter

which is not edifying but which causes «corrupción de

costumbres, y muerte del alma»

19.

Given this

uncompromising attitude on the part of some churchmen, we should

not be surprised that authors (some of them also clerics) find

themselves in a somewhat ambiguous position. From our

vantage-point, four centuries distant, we are perhaps more aware of

the ambiguity than the authors could have been. Thus Pero

Mexía, in his Silva de varia lección (1540), which is a

piece of popularizing that takes little trouble to distinguish fact

from fiction, is able, without apparent self-consciousness, to

condemn books which deal with fantasies. In Part in, Chapter 2,

where he discusses the invention of printing and its benefits, he

adds: «No niego, que se

haya tomado licencia demasiada en imprimir libros de poco fruto, y

provecho, de fabulas, y materias, que mejor fuera no aver moldes

para ellos. Porque destruyen, y cansan los ingenios, y los apartan

de la buena, y sana leccion, y estudio; pero el vsar mal alguno de

el Arte, no le quita à ella su bondad, y

perfeccion»

20.

Mexía would

probably have argued, if pressed, that what he was offering was

edifying matter, and while he might have resented some of the

connotations of the word «popularizer», he would

scarcely have objected to the principal meaning. On the other hand,

the author of El

Crotalón (written about 1553 but not printed until

the nineteenth century) knew very well, whoever he was, that his

satire belonged to a «profane» tradition, but his

argument was that only by clothing his moral in profane garb could

he make it acceptable to the average reader: «Tengo entendido

el común gusto de los hombres, que les aplace más

leer cosas del donaire: coplas, chanzonetas y sonetos de placer,

antes que oír cosas graves, principalmente si son hechas en

reprensión; porque a ninguno aplace que en sus flaquezas le

digan la verdad, por tanto procuré darles esta manera de

doctrinal [sic] abscondida y solapada debajo de facecias,

fábulas, novelas y donaires: en los cuales, tomando sabor

para leer, vengan a aprovecharse de aquello que quiere mi

intinción»

21.

Less than half a

century later, we find Mateo Alemán also profiting, in his

Guzmán de

Alfarache, from the use of a profane tradition, but at the

same time strenuously proclaiming his separateness from it, both by

regular and explicit sermonizing throughout the text and in his

prefatory remarks, in which he accuses some of his readers of

paying no heed to the moral teachings of the wise, and of being

satisfied instead with «lo que dijo el perro y respondió

la zorra»

22.

This is obviously a reference to popular literature, or, if one

wishes, «sub-literature».

Five years later,

in 1604, in the prologue to La pícara Justina, Francisco López

de Úbeda seems to feel the need to draw the distinction even

more clearly (and so, by protesting too much, making us even more

aware of the ambiguity of his position). He refers to the growing

number of profane plays and books which are «tan

inútiles como lascivos, tan gustosos para el sentido cuan

dañosos para el alma»

. The effect on

public morality, he says, is very serious, because the ordinary

public will read anything that gets into print or watch anything

that reaches the stage, no matter how bad or harmful it is. He

claims that «no hay

rincón que no esté lleno de romances impresos,

inútiles, lascivos, picantes, audaces, improprios,

mentirosos, ni pueblo donde no se representen amores en

hábito y trajes y con ademanes que incentivan el amor

carnal»

23.

López de

Úbeda's remarks about the stage remind us that there was a

long and bitter controversy about the propriety of the Spanish

Golden-Age theatre. Many documents have been collected and

published, and they need not be quoted at length here24.

Mention of the theatre, however, brings us to the author whose

position is probably the most ambiguous of all: Lope de Vega, who,

according to one critic, «había hecho más

daño con sus comedias en España que Martín

Lutero en Alemania»

25.

In Lope's play La

octava maravilla, written about the same time as his

Arte nuevo, a

master and servant discuss printed ephemera. The servant has come

across a pamphlet which states that in Granada a man has given

birth. The master is scornful. The servant, surprised, asks

«¿Está de molde, y te

burlas?». This question gives the master a

chance to comment on the folly of the general public, which will

believe anything that gets into print, and on the dangerous lies

spread by such ephemera26.

Here we glimpse a distinction which I shall discuss later: the

distinction between the vulgo, the ignorant public, and the discreto, the educated,

discriminating individual.

In a slightly later play, Fuenteovejuna (c. 1612-14), we find another aspect of Lope's attitude to the press. Fuenteovejuna is set in 1476, and in it two characters discuss the recent invention of printing. One, who has been to university (and who is therefore arguably a discreto) admits that printing has preserved and disseminated much useful knowledge; but he also claims that it has lent an air of authority to rubbish, and worse, that people are printing rubbish under the names of serious authors, whose reputations suffer thereby. As the commentators tell us, this is Lope himself, jealous of his reputation, complaining that others are profiting by it. And although the other character, an unlettered but shrewd peasant, is allowed to make the counter-claim that printing is important, the first character is given the last word, the gist of it being that people managed very well before printing was invented27.

Lope's concern for his reputation is well known: we find it also in the prologues of his partes de comedias. The most interesting expression of this concern is found in a memorandum written about the same time as Fuenteovejuna, or a little later28. In it Lope develops the criticism that the reputation of serious authors is suffering because unscrupulous people are using their names to promote the sale of pernicious rubbish. He refers to the kind of ephemera mentioned by López de Úbeda, which was being sold in the streets to the detriment of the Faith and public morals. He expresses particular concern about what we might call gutter-press sensationalism, which was all the worse for being untrue. There are writers, he says, who invent stories about men raping their daughters, killing their mothers, conversing with the devil, denying the Faith, and so on, and who (he might have added) then relate in full gory detail the punishments allegedly imposed on these imaginary criminals. Lope implicitly or explicitly blames all those involved in the book trade for this situation: public, authors, printers, those in charge of approving books for printing, booksellers and particularly sellers of ephemera. As for authors, he not unnaturally makes a distinction: there are serious and respectable authors (among whom he names himself), and others.

We are fortunate

in having the views of a «respectable» bookseller to

set against those of a self-confessed respectable author. The

bookseller is Juan Serrano of Seville, and although his memorandum

has no date, it must have been composed in late 1624 or early 1625.

Serrano was concerned about illegal imports of pernicious foreign

books, but he added that «si no fuera por el freno del

Santo ofiçio [los ynpressores destos Reynos] hiçieran

peores cossas que los estranjeros por auer poco que haçer

los gastos grandes las neçesidades muchas y aber quarenta y

siete maestros en castilla y andaluçia que con solos

treçe o catorze que hubiera no se hiçieran las cossas

tam perniçiossas que se

imprimen»

29.

He blamed the public as well as the desperate economic straits of

the printers, and evidently felt that both public and printers

could be partially protected if imported books were better

controlled.

The date of this document is interesting, for it shortly precedes the ban imposed on 6 March 1625. If the authorities were influenced by it, they ignored its suggestions, as they had ignored those made by Lope earlier. Neither Serrano nor Lope counselled a ban on the printing of novels and plays, and although Lope was no longer on good terms with Tirso de Molina, he can have derived little consolation from the fact that Tirso was singled out for writing «comedias... profanas y de malos incentivos y ejemplos». The nature of the ban is strange, and this is a good time to examine its threefold effect: on the public, on authors and on the trade.

In the case of the public, only those who were literate would be directly affected. But who made up this literate public, and what percentage of Spain's population did they form in the Golden Age? Since this question has been little studied, I may be excused for dealing with it here at some length.

Reliable census figures on adult literacy are not available until the nineteenth century. According to Professor Cipolla, Spain, with an adult illiteracy rate in the mid-nineteenth century of seventy-five per cent, was at the bottom of the European league, surpassed only by the Russian Empire and (possibly) by Italy30. It does not follow that Spain's illiteracy rate must therefore have been even higher two or three centuries earlier: as Cipolla points out, «there was no linear progress in the development of literacy after 1620»; in Europe in general, education was adversely affected by political and economic instability during the seventeenth century (pp. 52-53).

The only figures on which we can base estimates of literacy in Golden-Age Spain involve signatures in parish registers, and these are scarce because the priest generally did the signing. R. L. Kagan quotes one example where he did not, over a three-year period in a parish in Burgos: the years 1587-89, when Burgos was still a major city31. During this period ninety-eight children were baptized, and in sixty-nine cases (seventy per cent) the child's godfather did not sign the register. This figure is not a reliable guide, for several reasons. First, the percentage of the population able to stumble through a printed text was higher than the percentage of people able to write, or even to sign their name32. Second, and conversely, there was a tendency to choose literate men as godfathers. Third, the figure takes no account of women, and female illiteracy is generally supposed to have been higher, possibly substantially higher, than that of males. Finally, figures from a still large and thriving town permit no conclusions to be drawn about small villages, in which most of Spain's population still lived: Kagan points out that it was common for villages with less than 100 vecinos (reckoned as equivalent to 500 inhabitants) to have no inhabitant, not even the mayor, who could sign his name (pp. 23-24).

To these rather unhelpful figures we can add other scraps of inconclusive evidence. Pedro Fernández Navarrete wrote in 1621 that there were thirty-two universities and 4,000 grammar schools in Spain33. The round figure of 4,000 may be an over-enthusiastic guess, but the number of universities is not. Kagan has calculated that at their height, in the last quarter of the sixteenth century, the universities in Castile had 20,000 students, an estimated 3.2 per cent of the male population of university age (p. 199); then, as now, students tended to drop out, and first-year students (average age eighteen) represented almost 5.5 per cent of their male age-group. Only very complicated calculations would allow us to guess how many of the adult male population living at any given time in the early seventeenth century had at some stage attended university, but it must have been considerable. We do not know what percentage of the male population managed to complete a year at primary school (the usual time required to teach literacy), but it was clearly much higher than the 5.5 per cent which went on to first year at university.

The Cortes of 1555, mentioned above, apparently had cause to believe that «men, boys and girls and other kinds of people» were being corrupted by chivalresque novels, presumably in substantial numbers, otherwise why should they show such concern? As we have seen, St Teresa was able to read these books, although it has been assumed that she was exceptional; on the other hand, as she tells us in the first two chapters of her autobiography, not only could she and her brother read lives of saints before she was twelve (her age at her mother's death), but her mother could also read. (The petition of the Cortes actually claims that mothers would go out, thinking that they were leaving their daughters safe at home, whereas they were corrupting themselves by their reading). If we turn to the life of Sor María de Ágreda, who was born in 1602, we are told that both parents took pains in the education of their children, and, in particular, that María's mother taught her to read34. St Teresa's family was comparatively well-off, and this certainly accounts for the availability of reading-matter, if for nothing else. However, the autobiography of Alonso de Contreras, who was born in Madrid in January 1582, and whose parents were poor, states that Alonso was «going to school and writing a large I round hand» more than a year before he enlisted in the army in 159535. Alonso does not say whether his school depended on charity or on fees, but free schools were run by religious orders in most large towns, and St John of the Cross was taught to read and write in one of these, the Colegio de la Doctrina in Medina del Campo. His widowed mother was by this time (John was about nine) practically destitute36.

For evidence of later date than this, we can perhaps turn to Zabaleta's Día de fiesta por la tarde, first published in 1660. In Chapter 6, Los libros, he writes of a girl wasting her afternoon in reading a volume of plays, of a married man doing likewise with a book of love-stories, and of a youth spending his as fruitlessly in writing a poem for a literary academy37. With Zabaleta, who is producing a piece of imaginative writing, we are on the border-line of what can be considered as evidence. What he describes may be typical, but it is also fictitious. There are many other references in pieces of creative writing to individuals or to groups of people who are either literate or illiterate (two examples from Lope have been quoted), but their real value as evidence is small. I shall refer to one more, Antonio de Mendoza's El premio de la virtud, a play written probably before 1621 which deals with the life of Pedro Guerrero, Archbishop of Granada from 1546 to 1576. We first meet the future prince of the church as a young ploughman being chided by his father for wasting his time reading coplas, which were the only reading-matter he could find. This should remind us that verse chapbooks were still being used as reading-primers in the late eighteenth century in Spain.

If any conclusions can be drawn from this evidence, they would seem to be as follows: first, in Golden-Age rural Spain (as in nineteenth-century rural Russia, for which figures are available), the illiteracy rate was very high, probably over ninety per cent; secondly, in the towns it must have been substantially lower, for urban Spain underwent an educational revolution during the sixteenth century as a result of the policy, initiated by Ferdinand and Isabella, of recruiting the growing number of civil servants from the middle class, for whom the necessary education was provided by the numerous grammar schools and universities. One hesitates to suggest an overall figure, but if the literacy rate were as low as ten per cent, then about 800,000 people could read, and read to others if need be; if it were as high as twenty per cent (and it can scarcely have been much higher), then the total was about 1,600,000. Madrid and Seville, with a combined population of 200,000 or so in 1600, might well have had a thirty per cent literacy rate, or 60,000 readers.

One should not

leave this subject without referring to Cipolla's thought-provoking

remark that «after the fifteenth century,

technological progress in warfare required, and at the same time

was based on, an adequate supply of literate soldiers... Societies

which produced an increasing number of literate soldiers had a

decisive advantage over those that failed to do so»

(p.

23). We do not have to conclude that Hernán Cortés

and Bernal Díaz managed to conquer Mexico because they were

able to write such good reports of how they did so (!), but it may

be that Spain's sixteenth-century military superiority was due to

her educational revolution, that is, that she then had a higher

literacy rate than her European rivals. I do not claim that this

was the case; I merely mention it as a possibility which

is partly corroborated by Kagan's research on early modern Spanish

universities38.

While the number of readers affected by the ban was numerically considerable, it was very small in proportion to Spain's total population. As a modern novelist has said, printed books are «self-administered in private». On the other hand, the play in performance, «consumed... by large masses in places of public resort», was not affected39. When we remember that the Spanish censors appear to have cared more about what was said in public on the stage than about what was read in private, we can only find this curious40. Obviously the attack on Tirso made Tirso in particular, and his colleagues in general, more careful about what they wrote in their plays, but it seems clear that the section of the public least likely to be affected by the ban was the vulgo, the least discriminating, most gullible, and so, in theory, the most likely to be depraved. By the same token, those most likely to be affected were habitual readers of novels and plays, discretos, those less likely to be corrupted.

No author is recorded as having starved to death because of the ban. Playwrights made their money, if they made any, by selling manuscript plays to stage-managers rather than by printing them. Besides, both playwrights and novelists could make use of Aragonese printers. Quevedo had his Buscón printed in Zaragoza in 1626. Lope's El castigo sin venganza, a masterpiece to which an over-zealous censor might easily object, was printed in Barcelona (ostensibly, at least) in 1634. Again, an author could produce a hybrid which defied classification, or a novel disguised as history: Lope's Dorotea (Madrid, 1632), which he called an «acción en prosa», is an example of the former, and Pérez de Montalbán's Vida y purgatorio de San Patricio (Madrid, 1627), called a novela a lo divino in the preface, is an example of the latter41. Finally, of course, authors could simply wait. Lope died in 1635, too soon to benefit from the lifting of the ban, but Tirso and Calderón were able to publish collections of their plays in Madrid in the mid-1630s, after it was lifted. In short, there is no evidence that authors suffered real hardship, probably because none of them derived his principal income from printing what he wrote.

The effect of the ban on the book trade is hardest of all to assess, for reasons given already. The fall shown by the graphs of dated items in Castile corresponds to a large extent with the imposition of the ban, but there are several reasons for believing that the correspondence is not a straightforward one. First of all, the recovery after the ban, where there was one, was not sustained. Secondly, dated output from Seville, a major centre, was already falling before the ban was introduced. Finally, Zaragoza, an Aragonese city which ought to have profited from the ban in Castile, apparently went through its worst decade precisely during this supposedly profitable period. We know that there were attempts to evade the ban: Alonso Pérez, the father of Pérez de Montalbán and one of Madrid's most important booksellers, was caught in 1627, along with his printer, while trying to reprint Quevedo's Buscón42. We are not likely to discover how many times the ban was evaded successfully. The picture was probably not affected by the government's short-lived attempt to introduce a tax on books in 1634. The attempt no doubt reflects the continuing desire of the authorities to find some way of restricting the output of books, but the resulting outcry from the booksellers is even more significant in that it indicates how desperate they were. The tax was remitted by royal decree on 27 June 163643.

If we try to clarify matters by undertaking an exercise suggested above, namely, the drawing up of a graph of seventeenth-century Madrid printing-houses, the

result, even allowing for distortions, is surprising. The graph bears almost no relation to the graph of dated items produced. There is a rise in the ten years or so prior to 1625, but it corresponds to a much greater rise in output. The rise then stops, but the fact remains that while thirteen firms were working in 1625, there were still twelve in 1635. Moreover, the peak (eighteen firms) comes in 1675. In that very year Cabrera Núñez de Guzmán stated that there were fifty printers (counting masters and journeymen) in Madrid. He added that they were very poor because they lacked work: much the same remark as Serrano had made half a century earlier44.

Cabrera was a man with a keen interest in the book trade. He makes other statements which we know to be accurate. If we accept his figure of fifty, we can see how part of the enigma may be explained. It takes a minimum of three people to operate a printing-house efficiently: a compositor and two pressmen (the puller and the beater). But a master who had little work could lay off one pressman, making the other work «at half press», thereby cutting output by more than half45. In times of dire stringency, the master could work alone, alternately composing and printing at half press. This would reduce output even more. If prosperity suddenly returned, a master with two presses in his shop could take on four pressmen and two or more compositors, bringing his output to many times what it would have been had he been reduced to working alone. (Between 1564 and 1589 Plantin never had more than five or fewer than three workmen per press, although the number of presses in use ranged from two to sixteen: he simply took on or laid off men as production dictated)46. If Cabrera's figure is correct, there was an average of less than three qualified men per printing-house in Madrid in 1675. This means, even allowing for apprentices, that many of the firms must have been barely viable single-press concerns, depending for survival on what the trade calls «jobbing». As Serrano's document shows, this situation of too many firms competing for too little work existed before the ban, although the ban may have aggravated it.

In other words, the ban, like some other reforms put forward during the early part of the reign of Philip IV and his minister Olivares, was badly conceived, misdirected and unsuccessful. By dealing with novels and printed plays, it aimed at that small section of the public which was least likely to be corrupted by what it read; it ignored the problem of the potentially bad effect on the unlettered or barely literate public of the kind of ephemera to which Lope and others had drawn attention; it had little effect on serious authors who were already writing; and, as I shall argue presently, it probably increased the desperation of an already desperate book trade.

On 13 June 1627,

the government tacitly admitted some of the failings of the 1625

ban by issuing a new decree regarding printed matter. Ephemeral

material had not previously needed to be approved and licensed as

«real» books were, but the new law demanded that it

should be. The reason for this change is evident from the clause

which reads thus: «Encargamos

mucho que aya y se ponga particular cuydado y atención en no

dexar que se impriman libros no necessarios o conuenientes, ni de

materias que deuan o puedan escusarse o no importe su lectura, pues

ya ay demasiada abundancia

dellos»

47.

The intention clearly was that the licences now required for

ephemera should have the effect of reducing the amount printed. By

implication, the material mentioned by Lope, Serrano and others

would be involved; but any seasoned finder of loopholes will note

that the terms of the clause are by no means precise.

The same decree

contained another clause: «Y todo quanto se huuiere de imprimir sea con

fecha y data verdadera y con el tiempo puntual de la

impressión, de forma que pueda constar y saberse quando se

haze, y lleue y contenga también los nombres del Autor y del

impressor»

. Perhaps this was inspired in

part by an intention to control further the production of ephemera;

but it must also reflect an attempt to discourage would-be evaders

of the ban of 1625. Heavy fines and banishment were prescribed for

infringement.

Assessing the effect of this second decree is even harder. It involves at least a brief examination of the basic economics of printing, of the development of the Spanish book trade, and of its relationship with its public, a relationship which also affects the author himself.

Long-term capital investment is vital for a successful printing industry, especially if large firms are to be involved. I have argued elsewhere that Spanish printing-houses, like all Spanish industry, were eventually starved of capital investment48. As I have suggested above, one result of this was that Spanish firms grew smaller and more numerous in the course of the Golden Age. A second, related result was that firms were forced to work on an increasingly short-term basis. The shortest-term basis of printing is jobbing, or ephemera. It could take years to print a great folio and many more years to recover the initial outlay in sales. On the other hand one press could print 1,500 copies of a single sheet of verses in a day. Folded twice to make a pliego suelto, the most rudimentary form of book, they could be sold in hundreds to middle-men the next day, and the money used to buy more paper, print another pliego, and so on. These are theoretical figures, but they can be supported by real examples. For instance, we know that one pliego by Juan López de Úbeda ran through eight editions in a year, giving a grand total of 12,000 copies (at 1,500 per edition)49. Estebanillo González tells us that in 1630 or so he bought a hundred copies of one pliego from a blind man, who had himself bought his stock from a printer at Córdoba50. The text does not tell us the size of the blind man's stock, but implies that it was considerable.

Printers, even prosperous ones, have always produced some ephemera or jobbing work in order to maintain a steady income while awaiting the recovery of their investment in large items. What is important in this context is to discover when Spanish printers and publishers were forced to rely more and more on the quick turnover from ephemera. As indicated earlier, one can draw some conclusions from old inventories and other sources, particularly such statistics as have been compiled for surviving ephemera.

To judge from surviving inventories, the Spanish printing industry was no different from other industries in Spain: that is, it was in difficulties before 1600. The highest point of prosperity seems to have been about 1570, or at any rate before Philip II's second bankrupty of 1575. Printers then cast their own type from their own matrices; their stock of cast type might be over 3,000 pounds, their number of presses up to five. A century later they could no longer afford the capital outlay needed for matrices, and bought their type ready cast. Their stocks of cast type ranged from 600 to 1,000 pounds, and if they had two presses, only one would be in full use. If we examine the quality of the product, we find that the best Spanish books printed before 1570 compare honourably with books printed anywhere. By the end of the century the poorer paper, type and presswork are quite noticeable. By 1650 Spanish printing was possibly the worst in Europe (see note 2, p. 815).

Statistics for surviving ephemera are much less complete than one would wish, although the reasons for this will shortly become clear. We can begin with verse ephemera, which has a very venerable ancestry in Spain. Don Antonio Rodriguez-Moñino's list, which goes up to 1600, begins with eighteen incunabula. For the sixteenth century he lists 1,179, only 527 of them dated. Over half of the dated ones were printed in the last twenty years of the century51. No one has tried to produce such a list for the seventeenth century, but the figure must run to several thousands, perhaps to five digits.

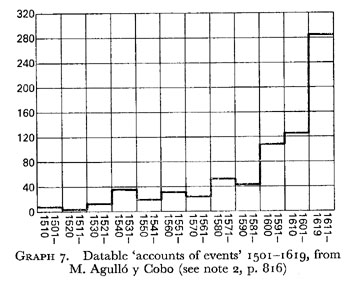

Another main type of ephemera is relaciones de sucesos, or accounts of events, not necessarily true ones, as Lope pointed out. Doña Mercedes Agulló y Cobo has recently made a list of those printed from 1477 to 161952. I give a graph of her figures from 1501 onwards, by decades. With this arrangement, we must wait until the decade 1571-80 before the figure fifty is reached. In the last decade of the sixteenth century the graph begins to rise markedly, and the last nine years show an average of more than thirty-one items a year.

A third kind of ephemera, more substantial, is the comedia suelta, normally issued as three to five quarto gatherings held together by what is known as «stabbing». There are very few before 1620, no doubt because the comedia was not fully established as a popular art-form until the end of the sixteenth century. Comedias sueltas grew rapidly in numbers after 1650, and continued to be printed for another two centuries. The pressmarks of the theatre section of the Biblioteca Nacional run well into five figures, but one pressmark can denote a bound volume of as many as twenty sueltas. Would-be cataloguers have understandably been intimidated.

It may be objected, first, that there is a potential distortion in survival-figures; that the earlier an item was produced, the less likely it is to have survived. To a degree, especially when natural catastrophes or human accidents are considered, this must be true. Paradoxically, however, the contrary is also true, in that antiquity encourages preservation. The average intelligent person who finds a five-year-old newspaper lining a drawer which is being tidied out will throw the paper away. If the newspaper is a hundred or even only fifty years old, it will more likely be kept: the older, the more likely. The mortality-rate of ephemera is rather like that of dwellers in unhygienic slums: it is highest in infancy and early childhood.

It may also be objected that such precise figures as are available do not cover the years around 1627, that I am arguing from extrapolations, and on the assumption that trends were maintained. This is true. There is no satisfactory retort. I can only say that the figures suggest that production of ephemera rose enormously from the last quarter of the sixteenth century on, and that while the rate of survival no doubt varies, it has always been very low53.

Some more evidence may be adduced, particularly with regard to the latter argument. As already stated, 12,000 copies of one pliego by J. López de Úbeda were produced in the late sixteenth century. In 1970 Don Antonio Rodriguez-Moñino knew of no surviving copy. Even if 120 copies were found in obscure libraries (and any worker in the field knows that this is a huge number), the survival-rate would be a miserable one per cent. Let us take another example from a century later. In 1683-84 Samuel Pepys visited Cádiz and Seville, where he bought ninety-nine different pieces of ephemera which are now in Cambridge54. Most are verse and plays. Many have no date and some have no imprint, but it can be deduced by typographical and other means that ninety-four were printed in Seville in the fifteen years before Pepys bought them (i. e. 1670-84). While working on the plays (none of which has an imprint), I made a list of 187 other Seville items printed during that period, a total of 281. If we examine Escudero's list of dated Seville items for the same period (see graph 2), we find only ninety-nine. If we count number 1757 as seven items, and eight undated items which probably belong to the period, there are still only 113 (1757 consists of seven works by Francisco de Godoy. Although Escudero saw all seven bound in one volume, I believe they were meant for separate issue). Thus the standard Seville bibliography under-records output in items by sixty per cent for 1670-84 (to our knowledge). Over ninety-eight per cent of the unrecorded items are ephemeral.

Under-recording is not confined to Seville. Between 1651 and 1700, Pérez Pastor records that output from Toledo, which by then had only one printing-house, was sixty-seven items (see graph 4). Of this number, twenty-five are pliegos of carols. Their normal size is one sheet. Seven more items run to five sheets or less (the figure five is arbitrary, but it is the usual upper limit for comedias sueltas). Thus almost half of recorded Toledo output for 1651-1700 is ephemeral. For some years (e. g. 1667, 1675, 1690), only pliegos of carols are recorded; for others (e. g. 1651, 1652, 1656), nothing. No printer could survive on this basis. If the Toledo printers had no other livelihood, they must have produced far more. Pérez Pastor is like Escudero in that nearly half of his recorded items are ephemeral. Thanks to Pepys, we know that the records of Escudero are incomplete, especially for ephemera. We have no Pepys to help us in Toledo, but we can reasonably conclude that much has been lost.

I make these points not in order to belittle the work of early Spanish bibliographers, but to show that their records of dated items for seventeenth-century Spain (and graphs based on them) give a false impression of what was being produced and, presumably, read. Or, to put it another way, the decree of 1627 appears to have had no effect, either in limiting the production of ephemera or in making printers add names and dates to what they printed.

I say «presumably read». The question of the kind of public which bought these items and for which the printers were therefore catering is a crucial one. As E. M. Wilson has shown, some of the best old ballads, and the work of what are now classical Spanish authors, were disseminated in ephemeral form55. But yet, as Alemán, Francisco López de Úbeda, Lope, Serrano and others pointed out, a great deal of rubbish was being produced as well. The conclusions of Doña María Cruz García de Enterría regarding verse ephemera are that rubbish gradually came to predominate in the course of the seventeenth century56.

The big rise in production of ephemera in the late sixteenth century must mean, I suggest, that the printers were aiming at a wider public in an effort to overcome their economic difficulties. To judge from the literary quality of the product, the intended purchasers were still to a large extent discretos. The public's favourable response (and the continuing economic problems) encouraged the trade to aim still wider. As the seventeenth century advanced, an increasingly less «literary» (and less literate) public found itself interested in «literature» which stimulated it enough to demand more, by buying what the trade was providing; and so the process went on, accelerated by the decree of 1625, and apparently not reduced by that of 1627. In order to survive, the trade found itself increasingly compelled to cater for the vulgo57.

(Here I feel obliged to insert a parenthetical disclaimer. I do not mean to imply that I am drawing an immovable line between the two categories of discreto and vulgo. These are really convenience-labels given to opposite ends of a broad spectrum of readers. Each kind of ephemera would attract readers from a somewhat different band of this spectrum, and no doubt works «intended» for the consumption of one band were also read by others. The lower ranks of the vulgo included people who could not read at all, and whose contact with the printed word was therefore limited to what could conveniently be read aloud (or recited, or sung) to them. By discretos I mean a category composed of people capable of exercising judgement on the basis of literary criteria; by vulgo I mean those incapable of exercising such judgement)58.

The next point to consider, and one which is even more crucial, is the effect of this «dual» and gradually changing public demand on the suppliers: the authors themselves. Here three relevant subjects may be considered: the public theatre; authors' prologues, dedications, or other forewords to their work; and the nature of certain works themselves.

The public theatre

is marginal to my arguments, which mainly involve the book trade,

but it seems to betray the same symptoms. The most striking thing

about Spanish Golden-Age plays is their quantity. Between them the

three major dramatists wrote about 1,500 dramatic works (if we

accept Tirso's own figures, though not Lope's «mil y quinientas»). The

overall total must run to five figures. The public was so hungry

for plays that two, three or up to nine authors got together,

thrashed out a plot, and went off to write their act, or part-act,

separately. Long runs were rare: «novelty» was the

public's watchword. Not only was public demand insatiable, but

there is ample evidence that the most vociferously critical section

of the public was the least educated, the so-called mosqueteros

(«groundlings»). They could, and did, ruin plays by

whistling, shouting and even ringing bells brought specially for

the purpose59.

They had to be catered for, certainly by unashamed pleas for

applause in the closing lines of a play, arguably by the writing of

the sort of play that was known to appeal to them: saucy, gory, or

both. Here one must return to the ambiguous stance of Lope de Vega.

There is no doubt that Lope was a serious author (even if a

self-confessed one) and that he wanted his work to be appreciated

by discriminating people, discretos. While we know only too well that his

tongue was in his cheek when he wrote his Arte nuevo, we can produce plays as

evidence to support these well-known lines: «Porque como las paga el

vulgo, es justo / hablarle en necio para darle

gusto»

60.

Against the serious and thought-provoking treatment of marital

infidelity that we find in El castigo sin venganza we can place the bloody

monstrosity of Los

comendadores de Córdoba, which ends with a stage

littered with corpses of men, women and animals; or the

lighthearted (and, some might say, male chauvinist) attitude to

adultery that we find in the significantly-named El castigo del discreto. There

is no doubt that Lope had two hats, and wore one when writing for

the vulgo, the

other when writing for the discretos (he could also wear both at once). One

could argue that a lesser artist would have worn only the

first.

As we can discover

from prologues to their readers, authors became aware at an early

stage that they were catering, as it were, for two publics. In the

prologue to his Galatea (1585), addressed to his

«curiosos

lectores», Cervantes describes how some authors,

«con desseo de

gloria, se auenturan; otros, con temor de infamia, no se atreuen a

publicar lo que, vna vez descubierto, ha de sufrir el juyzio del

vulgo, peligroso y casi siempre

engañado»

61.

The concept of the «two publics» becomes most obvious

when authors provide two prologues, one addressed

«al vulgo», the other

«al discreto lector». Mateo

Alemán (Guzmán, Part I, 1599) was the first

to make this distinction, but others did the same, or, if they had

only one prologue, addressed both kinds of reader in it. Thus Ruiz

de Alarcón's Primera parte de comedias (1628) has a dedication

to the Duke of Medina de las Torres, and an address al vulgo, whilst his

Segunda parte

(1634), dedicated to the same Duke, has an address al lector, which begins

«Qualquiera que tu seas, o mal contento (o bien

intencionado)...». Salas Barbadillo was also

fond of the double prologue. His El cortesano descortés (1621),

dedicated to Pablo and Jorge Espínola, contains an

al vulgo; so

does his Fiestas de

la boda de la incasable mal casada (1628), which is

dedicated to Don Agustín Fiesco. His El curioso y sabio Alexandro

(1634) is subtly different: apart from the dedication, it contains

an address «A los que leyeren, y

también a aquellos que escucharen leer a

otros». We get variations such as Juan de

Piña's prologue «Al mal

intencionado» (in Varias fortunas, 1627), or even cases when a

friend of the author takes it upon himself to attack the

vulgo for him

(as in Rey de Artieda's Discursos of 1605, which are prefaced by a sonnet

by Lupercio Leonardo de Argensola; it begins with the line «El vulgo vano (siervo de

la fama)...»

)62.

What all these

writers share is an ostensible contempt for the vulgo; contempt, but also,

frequently, fear: explicit as in Cervantes, merely implicit, or

present because its existence is denied. Into the last category

fall Ruiz de Alarcón's claim that his plays

«te miran con desprecio, y sin

temor» (Primera parte), or Vélez de Guevara's

prologue «A los mosqueteros de la

comedia de Madrid», in which he says that

«una vez tomaré la pluma sin el miedo de

vuestros silbos», the reason being that the

mosqueteros

are illiterate (El

diablo cojuelo, 1641). Even when the word vulgo is never mentioned,

dedications to patrons contain references to murmuradores, envidia, and

often take the form «I dedicate this to

you, Excellency, for your reputation is such that even the most

ignorant will not dare to criticize my work»

63.

Human nature being as it is, we may take it for granted that every reader considered himself discreto; in practice, many can have been no more discriminating than those self-appointed drama critics, the mosqueteros. Authors were in an unfortunate position. Their prefatory remarks show, I think, that they were aware of and alarmed by the existence of this indiscriminating public, which was everywhere around them, but to which no one would admit to belonging; a public which they could safely pretend to despise, but to which in practice many of them were forced to defer64.

Very few authors

were unaware of the vulgo-discreto dilemma. Perhaps only an

exceptional religious poet like St John of the Cross was

sufficiently unworldly to be completely oblivious of it. Of those

who were aware of the dilemma, some chose to reject the vulgo: here the

Góngora of the Soledades springs to mind, with his remark that

«honra me ha

causado hacerme escuro a los ignorantes, que esa [es] la

distinción de los hombres doctos, hablar de manera que a

ellos les parezca griego; pues no se han de dar las piedras

preciosas a animales de cerda»

65.

Another example is Pedro Soto de Rojas, the title of whose poem,

Paraíso

cerrado para muchos, jardines abiertos para pocos, is

self-explanatory. But the decision to write for the few can turn

into the sterile doctrine of art for its own sake. If we subtract

the exceptional ear and poetic imagination of Góngora from

his concept of art, then we are on the road which leads to the

vapourings of Trillo y Figueroa.

Other authors were

certainly tempted to take the easy way out. In 1605 Cervantes had

written that it was «mejor ser loado de los

pocos sabios que burlado de los muchos necios»,

while admitting that some found it «mejor ganar de comer con

los muchos, que no opinión con los

pocos»

(Don Quijote, 1, 48). Four years later Lope's

conclusion was that since the many paid, one should write down to

them.

Of course it was possible to cater for both discretos and vulgo, although it was harder. As eminent critics have argued, one of the strengths of Golden-Age Spanish literature was its closeness to its popular origins. The fact that great authors often drew on popular material for their best work meant that even the broadest public could find something to appreciate in that work. So long as there were some geniuses like Lope and Calderón, who could draw on popular material and turn a commonplace ballad or tale into a great play, Spanish literature could maintain a high standard without seeking refuge in a paraíso cerrado; but there was a growing number of writers who took commonplace material and turned it into commonplace plays.

No one will deny

that commonplace «literature» and commonplace writers

increased in purely numerical terms during the seventeenth century

in Spain. Nor can it be denied that they also increased

proportionally: when Gracián died in 1658, Calderón

was the only great writer left in Spain -and that almost

fortuitously, due to his longevity. When he died in 1681, there was

no one to take his place. What became of the new generation? Some,

certainly, wasted their talents in servile imitation. Were there

others who never stretched their talent, because they found it

easier to produce third-rate material for which there was an

ever-ready market? Dr García de

Enterría implies that this was so, at least of poetry:

«Los poetas

cultos, en la segunda mitad del siglo [diecisiete], se dedican a la

imitación de la poesía de cordel... La poesía

vulgar no experimenta así la urgencia de elevarse

estéticamente si ve que son los otros quienes se rebajan

hasta ella»

66.

Cervantes says that there were writers of this kind, writers who

wasted genuine talents on trivia, early in the seventeenth century.

But how many were they? How many great works were never written

because their authors were too busy making an easier living by

producing trash? These are not questions which can be answered. One

can only use circumstantial evidence to present hypotheses which

cannot be wholly proved or disproved.

As far as plays in

performance were concerned (and Cervantes was a frustrated and

unsuccessful playwright), Cervantes blamed the middle-men, the

stage-managers, rather than the public67.

The same is probably at least partly true of the book trade, where

the middle-men (printers and booksellers) must have put pressure on

authors to write what the booksellers considered

«commercial». A relatively typical example of the

attitudes of the middle-men can be found in this preface of a

newsletter of August 1689: «La Obra que doy al publico, me ha

venido de Francia toda entera, con amplia facultad de hazer della

lo que yo quisiesse. Por esto mesmo, en lugar de darla entera

à la luz de una vez, la darè en partes, teniendo yo

experimentado, que los Papeles curiosos de pocas ojas, penetran, se

leen, y se despachan mucho mejor, y mas prontamente que los

Libros... Darànse dos, ò tres al mes, mas, ò

menos, mientras duràre el material, segun el tiempo que

tuvieren nu[e]stras prensas, y segun gustare dellos el

Publico»

68.

In this case the printer-publisher has committed himself to the

expense of producing only two sheets (eight quarto leaves) on the

grounds that he knows that a work produced in parts will sell

better and faster than as a whole; there is also the clear

implication of «testing the water», and that he will

withdraw (with little loss) if demand does not meet expectation. We

can be sure that apart from printing costs, the only other possible

financial outlay involved the buying of a copy of the French

original (unprotected by copyright) and (perhaps) a translation

fee. There is none of the modern journalist's concern about the

reliability of his sources: he was trying to cash in on a wave of

Francophobia aroused by the outbreak of the war of the League of

Augsburg the previous year.

We should not blame such printers, easy though it may be to do so. Faced with rising costs and dwindling capital investment, they tried to survive by making what use they could of two circumstances in particular: Golden-Age Spanish literature's closeness to its popular origins, which meant that the vulgo had never been completely isolated from even serious literature; and the educational revolution in sixteenth-century urban Spain, which created a high urban literacy rate (the decline of educational standards in the course of the seventeenth century affected the literacy rate, but only gradually).

Unfortunately for the overall standard of literature, the greater part of the broad public for which these printers were forced to cater was as happy with the third-rate as with the first-rate, and readily consumed material which the authorities considered harmful. The literary decline would have taken place without the intervention of the authorities; it was well advanced before they intervened. Their decrees were a reflection, not a cause, of the economic malaise. If they had any effect at all, it was to increase commercial pressure, and to add the pressure to write what the authorities considered orthodox and morally edifying. Neither of these pressures is a good thing for literature, although I doubt if moral pressures were important in Spain's case. If any laws had an effect on Spanish Golden-Age literature, they were not those made by legislators, but the simple economic laws of supply and demand. The men who made the ballads did not care who made the laws of the nation69.

* * *

Critics are

already agreed that Spain's literary decline had a number of

causes, among them literary and social ones. There may be others as

yet unsuspected, and probably all are interrelated in ways which we

may spend years trying to comprehend. I merely suggest that one

cause depends on Steinberg's principle that literary movements

cannot be fully understood unless one takes account of the printing

press's influence on them. If the suggestion is correct, it may

still be argued that the press's influence on first-class

literature is negligible, or, at best, incapable of proof; that is,

it may be claimed that a first-class writer will say what he wants

to say, irrespective of the economic state of the book trade, and

that if his work is good, it will get into print. I would agree

wholeheartedly with the first of these claims, but with regard to

the second, I would quote the words of a modern British publisher:

«[Some] people argue that books which

should not be published now simply will not be published, and that

only the really worthwhile books will get through. This is

undoubtedly true to a certain extent, but it would be imbuing a

nasty economic crisis with too much good will to imagine that the

bad die and the good live. I certainly know from my own experience

that this is not happening and many innovatory and worthwhile books

which ought to be published and which, if published, would

eventually be influential and even commercially successful, given

time, are not now seeing the light of day»

70.

This, of course, is not proof; but it is evidence. There are many parallels between the book trade of seventeenth-century Spain and that of modern Britain: high costs; shortage of capital; the erosion of returns on investment due to inflation; and a large but generally indiscriminating public. It may be that when all these circumstances combine, they bring into operation a sort of Gresham's Law of literature, that is, that bad literature tends to drive out good. If such a law exists, then it is no accident that a literary revival took place in Spain in the 1770s and 1780s, for it was precisely then, during the enlightened despotism of Charles III, who did his best to revive Spanish industry, that printing and the book trade underwent a major economic recovery.