Publishing in El Salvador

Profiles of Editors and Publishers in El Salvador

The field of Salvadoran publishing, prior to the country's 1821 independence from Spain, shares the situation of other Central American countries, the local production of books es practially non-existent and its consumption are linked to importation, especially from Europe, but also from Mexico and Guatemala. Nonetheless, some exceptions stand out, for example, the publication of El puntero apuntado con apuntes breves (1746), by Juan de Dios del Cid, the first book printed in Central America. The book is a manual dedicated to the production of indigo and, curiously, it mixes popular wisdom with poetry.

In the post-independence decades, and even following the entrance of the printing press into the city of San Salvador in 1824, the number of books produced in local shops was reduced; in the majority of cases they were editions with few pages or of medium length. Nevertheless, the continuous importation of books, together with these productions on a small scale and the founding of newspapers and journals, tell us that the circulation and consumption of books had a certain vigor (as a mark of social prestige) and fed an up-and-coming market which, at the same time, drank from the flow of ideas that emerged in the academies and in literary groups. To this situation is added the appearance of various bookstores: Universal, Camino Hermanos, Mata y Centel and Dominguez y Rivas in the first decades of the 20th century.

The great leap in local publishing took place in 1953, when the first publishing house of the State dedicated exclusively to literary works was founded, the current Dirección de Publicaciones e Impresos (DPI). Its first director was the lawyer and poet Ricardo Trigueros de León (1917-1965), who for 12 years published the most outstanding writers of the times (Alberto Masferrer, Arturo Ambrogi, Miguel Ángel Espino, Salvador Salazar Arrué Salarrué o Hugo Lindo). At the same time, he created collections and spread Salvadoran literature beyond its national borders, which makes him its first official exporter. In the following years, the publishing house continued publishing the national literary patrimony and had notable achievements, such as the publishing of the Claribel Alegría's novel Cenizas de Izalco, which had appeared in Spain under the Seix Barral brand.

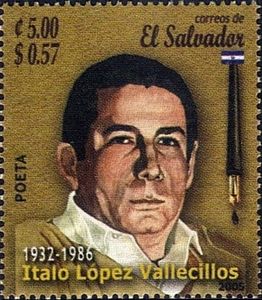

In 1958, the Editorial Universitaria Benjamin B. Cisneros started up, under the direction of the writer and journalist Italo López Vallecillos, its first director and one of the most relevant Central American publishers. He was the Director of the Editorial Universitaria Centroamericana (EDUCA), with its main office in Costa Rica, between 1970 and 1975, and from 1975 and 1983, of UCA Editores, which belonged to Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas (UCA), in El Salvador. The catalogues of these three publishing houses include important authors of the region, both from yesteryear and contempoary, in addition to scientific and academic publications.

The circulation of books, both national and imported (coming now especially from Spain, Mexico, and Argentina), was led by the Librería Cultural Salvadoreña, founded by Kurt Wahn around 1951, until its 1991 closing. In addition, the Librería Clásicos Roxsil, established in 1969, played a transcendent role as the distributor of literary classics (both universal and Salvadoran), especially when, beginning in 1975, some of the works were published by the Editorial Clásicos Roxsil. The bookstore and the publishing house were founded by the married couple José L. López y Rosa Serrano de López, who were succeeded by their daughter, Roxana López de Portillo the project director.

In the 70s, small alternative bookstores appear, like Pablo Neruda, Altamar (founded by the writer Hugo Lindo), Importadora Latinoamericana de Libros, La Teja which distribute less commercial literature meant for a cultured middle class which no longer saw books exclusively as luxury objects, but rather as an opportunity to satiate their literary and intellectual curiosity. Nevertheless, in the last years of that decade, the political climate entered into a complex spiral of violence which announced the arrival of the Salvadoran Civil War (1980-1992). Publishing and literature saw themselves deeply affected and altered.

In this setting, intellectuals, professors, writers and bookstore owners identified with leftist social movements which were critical of the military dictatorship were killed. In addition, the infrastructure of some bookstores was destroyed by the explosion of bombs during the struggle. Writers who, in the most cases, also had been publishers, like Miguel Huezo Mixco, o bookstore owners, like Salvador Silis (who had brought to El Salvador the first titles of the Spanish brand Anagrama and the Mexican Ediciones Era), decide to join the guerilla movement. Others are forced into exile. All of this led to a drastic diminishing of literary dissemination, which in turn led to the near absence of the book market. With culture relegated to a lower level before the urgency of the armed conflict, books and reading lost in some way their value in the social fabric. The cost of this cultural malnourishment was more clearly felt in the decades following the signing of peace.

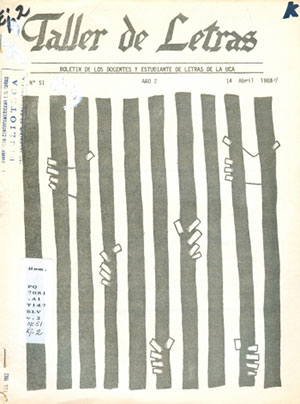

Nevertheless, university spaces acquired a protagonist role. The journal Taller de Letras, published in the 80s by the Departamento de Letras de la Univeridad Centroamericana (UCA), took charge of documenting the literature of that period: poetry, narrative, drama and essay, a task that before the war had brought about the State journal Cultura. UCA Editores published Pájaro y volcán (1989), an anthology compiled by Huezo Mixco which reflects the moment as it was lived: written and published literature in guerrilla camps. The manuscript, in fact, went out through clandestine channels until it arrived at the hands of the then-rector, the Jesuit Ignacio Ellacuria. In addition, this university publisher launched the Premio Nacional UCA Editores and published the winning works, such as La diáspora (1989), the first novel by Horacio Castellanos Moya. Also important was the work of literary groups who disseminated their handmade publicaciones in public squares, factories, syndicates, universities, etc.

In 1991, the previously mentioned Dirección de Publicaciones e Impresos (DPI) is reactivated, although it is behind the times and lacking in resources. The war has almost ended and a little later the end of the conflict becomes official with the signing of Acuerdos de Chapultepec (1992). In those first postwar years, a good number of writers, intellectuals and publishers return from exile, and others come down from the mountains... They share enthusiasm for the refounding of the pluralistic and inclusive culture through journals, newspapers, bookstores, publishing houses. Thus, there is a buy-in for culture as a vehicle of change and as a symbol of democratic and intellectual maturity, a direction that takes a step beyond the political pact that had put an end to the twelve years of war, the magazine and the newspaper Primera Plana are born, and the bookstore Punto Literario is started up. After a short while none of these undertakings will have survived. La DPI, first, under the direction of the poet Carmen González Huguet, and then under the writer Miguel Huezo Mixco, catch that enthusiasm; ambitious publishing projects are launched in tune with the winds of change, like the Biblioteca Básica of Salvadoran literature and collection Ficciones. In addition, the collection Orígenes is redesigned, now dedicated to the publication of complete works of canonical authors. Nevertheless, little by little that enthusiasm comes across a polarized society which will enter later into a new cycle of social violence. In addition, precarious aspects of the economic, political and cultural infrastructures become evident.

From the 90s to the present a proliferation of independent publishing houses, as well as those of universities, has taken place, in addition to the already mentioned ones, others have emerged, like Editorial Delgado or Editorial Universidad Don Bosco. The field of Salvadoran publishing continues to be marked by relevant obstacles: few distribution and business channels exist, and therefore there are limited budgets; a book market which is rather meager, the lack of fiscal incentives; the 1994 Ley del Libro continues to be inoperative, and lastly, the high degree of piracy. Even the DPI has not succeeded in solving distribution and commercialization problems. Hardly any editorials have opted for digital publishing and very few for translations.

The individual efforts of independent publishers, in spite of these obstacles, demonstrate that it is a job that is ruled more by vocation and less by marketplace rules. It self-sustains on the base of tenacity and optimism. Names like Istmo Editores, Editorial Arcoiris, Índole Editores, Canoa Editores, Editorial Rubén H. Dimas, Editorial Kalina, Zeugma Editores, Fundación Alkimia, Proyecto Editorial La Chifurnia, Laberinto Editorial, La Cabuda Cartonera and more recently Los Sin Pisto have shown and continue to show that this is the case.

Tania Pleitez Vela

(Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona)

Translation by Christopher L. Anderson

(Tulsa University)

Facade of the National Printing of El Salvador. Source: «History». National printing. Official diary.

Operator in the National Printing of El Salvador. Source: «History». National printing. Official diary.

Postage stamp with the image of Italo López Vallecillos. Source: Colnect.

Taller de Letras (1984) cover. Source: Taller de Letras Collection. Universidad Centroamericana «José Simeón Cañas».

Anthology cover Bird and volcano, edited by Miguel Huezo Mixco.

Bibliography

- GALLEGOS VALDÉS, Luis (1981). Panorama de la literatura salvadoreña. Del período precolombino a 1980. San Salvador: UCA Editores.

- HERNÁNDEZ, Alexander (2018). Las editoriales independientes en El Salvador (2006-2016). Tesis de Maestría en Estudios de Cultura Centroamericana. Universidad de El Salvador.

- LÓPEZ, Carlos Gregorio (2006). «La historia cultural en El Salvador. Un campo de estudio en ciernes», Diálogos. Revista Electrónica de Historia, vol. 6, n.º 2, pp. 98-109, en https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/dialogos/article/view/6216 [24 de noviembre de 2018].

- LÓPEZ VALLECILLOS, Ítalo (1964). El periodismo en El Salvador. Bosquejo histórico-documental, precedido de apuntes sobre la prensa colonial hispanoamericana. San Salvador: Editorial Universitaria.

- MOLINA JIMÉNEZ, Iván (2004). La estela de la pluma. Cultura impresa e intelectuales en Centroamérica durante los siglos XIX y XX. Heredia. Costa Rica: EUNA.

- PLEITEZ VELA, Tania (2012). Literatura. Análisis de situación de la expresión artística en El Salvador. San Salvador: Fundación AccesArte.

- TENORIO, María (2006). «Leer libros importados en el San Salvador del siglo XIX: Un vistazo del consumo cultural a partir de los periódicos», Istmo. Revista Virtual de Estudios Literarios y Culturales Centroamericanos, n.º 13, en http://istmo.denison.edu/n13/proyectos/libros.html [25 de noviembre de 2018].

- TENORIO, María (2006). Periódicos y cultura impresa en El Salvador: «Cuán rápidos pasos da este pueblo hacia la civilización europea», Tesis Doctoral, The Ohio State University.